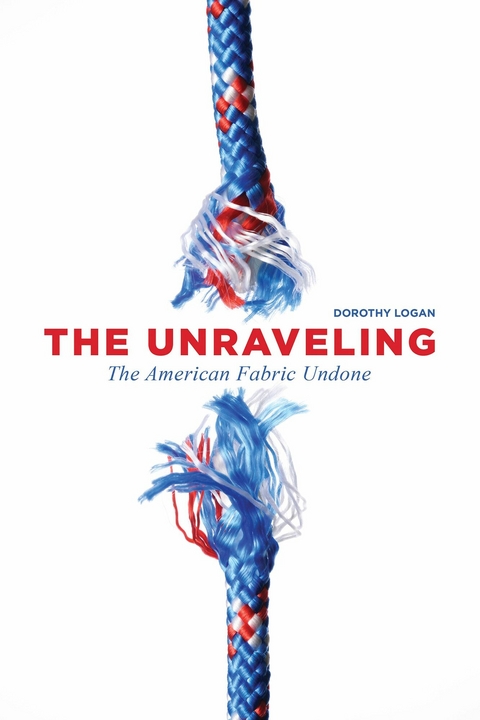

Unraveling (eBook)

198 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

978-1-6678-8456-1 (ISBN)

The fabric of American society is falling apart, and the beautiful tapestry that is the United States is unraveling. Part of the broken loom upon which that tapestry was woven is due to the shifting societal sands and cracks in the country's foundation. This political philosophy lays out what those loose threads represent and why American society is coming undone. "e;The Unraveling"e; offers ample reasons and arguments for how The Great American Experiment has failed and why there's no going back, but Dorothy Logan gives readers reasons to hope that America can weave its society back together.

Chapter 1

A Republic – If You can Keep it

We don’t live in a democracy. Or at least we aren’t supposed to be living in a democracy. Maybe we are living in a democracy now. If everyone believes we do and thus acts as though we do, perhaps we do live in a democracy. And if we have exchanged our republic for a democracy, we have willingly handed ourselves over to tyranny. And as we are constantly encouraged to do everything to strengthen democracy, we are being called to strengthen this tyranny over ourselves, and we voluntarily do so. It is quite a paradox.

What is a democracy, anyway? We often use the word where another is more accurate. Do we want to spread democracy? Or do we want to spread liberty? Do we want to protect democracy? Or do we want to protect our freedom? Are we afraid of threats to democracy? Or threats to our way of life? Democracy is not the same thing as freedom, yet too often people equate democracy with freedom. They resonate in the mind as one in the same. They are not.

Democracy is a type of governance that is simplistically stated as “majority rule,” popularized in our psyche by ancient Greece. In ancient democracy, individual citizens practiced direct sovereignty by participating in all the decision-making facets of the polis, decisions ranging from war and alliances with other governments to pronouncing judgments on their fellow citizens. While this direct democracy seems to offer a lot of power to the individual citizen, the reality is instead the complete subjection of the individual to the authority of the community. (Not to mention that the power rested only in the hands of ruling class men.)

Jean-Jacque Rousseau was a philosophe of the so-called Enlightenment whose writings informed the founders regarding the dangers of democracy. And if one reads Rousseau’s works today, what we see happening in The United States as part of the unraveling seems to align with his premises and explanations of and for democracy. It is through Rousseau’s writings we can understand the goals and motivations of those who embrace the notion that we live in a democracy – and should live in a democracy.

Rousseau’s basic premise is that man is inherently good but Society has made man evil. Savage man is the one who lives according to impulse, with no thought or contemplation, just addressing what he needs to do to survive any given day. So because man is inherently good, his natural impulses are naturally good. Therefore, morality is the result of following one’s impulses. (If it feels right, do it!) According to Rousseau, there is no moral right or wrong. No ethical conscience. No higher or transcendent self. Rousseau does not believe in a transcendent self at all. He affirms the essential unity and goodness of human nature by declaring that there is no difference between what one feels like doing in the moment and what one should do. They are one in the same thing. To Rousseau, morality is synonymous to uninhibited impulse. What someone thinks is a conscience, according to Rousseau, is just Society dictating to them what is right or wrong. Instead of a tension between transcendent ethical purpose and contrary inclinations, Rousseau assumes a tension between man and the institutions of conventional society. In other words, Society is the problem, not man.

“O Virtue! Sublime science of simple souls, are there so many difficulties and so much preparation necessary in order to know you? Are your principles not engraved in all hearts, and is it not enough, in order to learn your laws, to commune with oneself and, in the silence of passions, to listen to the voice of one’s conscience?”1

To some, this might sound like natural law – to some Christians out there, this might even sound like the “law of God written on man’s heart.” Do not be tricked. Remember that there is no conscience – just uninhibited impulse. According to Rousseau, we need to separate ourselves from the arguments of society, what society tells us is right and good. That is the only way we know what we should do. It really is the idea that if it feels good and right to you, then it is good and right for you – so don’t doubt, just do it!

This is the opposite of Winthrop’s argument:

“The first [type of liberty] is common to man with beasts and other creatures. […] The exercise and maintaining of this liberty makes men grow more evil, and in time to be worse than brute beasts: omnes sumus licentia deteriores. This is that great enemy of truth and peace, that wild beast[…]”2

Here Winthrop is saying that the freedom Rousseau is arguing as true freedom – the morality Rousseau is heralding as uninhibited impulse – is the opposite – to operate in such freedom makes men grow more evil (not good), and such liberty is the enemy of truth and peace.

“The other kind of liberty I call civil; it may also be termed moral, in reference to the covenant between God and man, in the moral law, and the politic covenants and constitutions amongst men themselves. This liberty is the proper end and object of authority […]” (Winthrop)

But Rousseau argues that the liberty of the beasts is better as “savage man” does not worry about what is right or wrong and has no imagination toward violence.3 Whereas Rousseau argues that society has made man evil (and thus civil man is evil, not savage man), Winthrop argues civilization is the solution, not the problem.

To Winthrop’s point, it does appear that boundaries and rules can in some instances provide for more freedom. For example, at a playground near a very busy road – think the Interstate (cars constantly zipping by, no breaks in traffic) – children will tend to stay close to the equipment even if there are a few acres surrounding the playground. However, put up a fence, and the children appear to have more freedom. They will play all the way up to the fence, even if it is only a few yards from the busy street. The fence gives them the freedom to use the extra acres around the playground. They may add games like kickball or tag to their playground romps. Without the defined boundaries, the children do not take advantage of all the freedom available to them. Give them a boundary, and they open their lives up to several more opportunities.

Rousseau’s argument is again, the opposite. It is the boundaries that cause the evil and restrict freedom. For example, there would be no trespassing (or looting or destruction) if no one owned property. Or at a more global level, there would be no competition between nations or societies – no wars – if there was no civilized society. If the boundary did not exist, one could never cross the boundary and thus there would be more freedom.

Therefore, Rousseau argues, mankind would be better off if we had never been civilized. But Rousseau has a problem. We have been civilized.

Rousseau identifies the problem (we have been civilized) – and then offers a solution: The “General Will.” According to Rousseau (the father of modern democracy), it is through the social contract with the General Will that the “goodness” of man can be recaptured within the “evil” of society itself. And this is democracy – it is through Democracy (the social contract with the General Will) that we solve the problem of being civilized.

“Find a form of association which defends and protects with all common forces the person and the goods of each associate, and by means of which each one, while uniting with all, nevertheless obeys himself only and remains as free as before.”

“Each of us places his person and all his power in common under the supreme direction of the general will; and as one we receive each member as an indivisible part of the whole.”4

This is how modern democracy works. Each person places himself or herself (or themselves) under the power and direction of the “general will.”

“At once, in place of the individual person of each contracting party, this act of association produces a moral and collective body composed of as many members as there are voices in the assembly, which receives from this same act its unity, its common self, its life, and its will.”

In Rousseau’s General Will, there are no more individuals! Just a collective body – and every member of the collective body has the same will. And that is okay. No one needs to worry!

“Since the sovereign is formed entirely from the private individuals who make it up, it neither has nor could have an interest contrary to theirs. Hence, the sovereign power has no need to offer guarantee to its subjects, since it is impossible for a body to want to harm all of its members…it cannot harm any one of them in particular.”

The “Sovereign” (government, in other words) does not need to guarantee any rights to the members because (Rousseau argues) that Sovereign cannot have interests contrary to the interests of the individual members. Thus, only the “general will” matters. The Sovereign’s will (the government’s will) dictates what society wants and needs – but more than that, it is the only true will of the people.

“The sovereign, by the mere fact that it exists, is always all that it should be.”

In Democracy, there is no individual. No individual will. The will of everyone in the society is the same. Even...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 16.1.2023 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung |

| ISBN-10 | 1-6678-8456-5 / 1667884565 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-6678-8456-1 / 9781667884561 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 1,9 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich