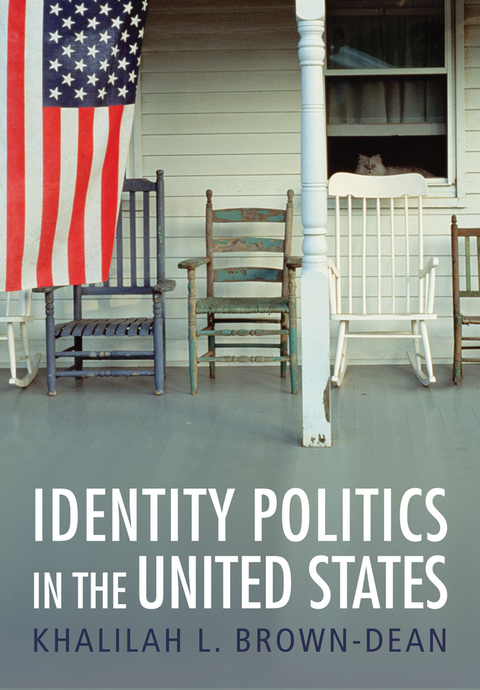

Identity Politics in the United States (eBook)

288 Seiten

Wiley (Verlag)

978-1-5095-3882-9 (ISBN)

In 2017, a white supremacist rally at the University of Virginia forced many to consider how much progress had been made in a country that, nine years prior, had elected its first Black president. Beyond these racial flashpoints, the increasingly polarized nature of US politics has reignited debates around the meaning of identity, citizenship, and acceptance in America today.

In this pioneering book, Khalilah L. Brown-Dean moves beyond the headlines to examine how contemporary controversies emanate from longstanding struggles over power, access, and belonging. Using intersectionality as an organizing framework, she draws on current tensions such as voter suppression, the Me Too movement, the Standing Rock protests, marriage equality, military service, the rise of the Religious Right, protests by professional athletes, and battles over immigration to show how conflicts over group identity are an inescapable feature of American political development. Brown-Dean explores issues of citizenship, race, ethnicity, gender, sexual identity, and religion to argue that democracy in the United States is built upon the battle of ideas related to how we see ourselves, how we see others, and the mechanisms available to reinforce those distinctions.

Identity Politics in the United States will be an essential resource for students and engaged citizens who want to understand the link between historical context, contemporary political challenges, and paths to move toward a stronger democracy.Khalilah L. Brown-Dean is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Quinnipiac University.

In 2017, a white supremacist rally at the University of Virginia forced many to consider how much progress had been made in a country that, nine years prior, had elected its first Black president. Beyond these racial flashpoints, the increasingly polarized nature of US politics has reignited debates around the meaning of identity, citizenship, and acceptance in America today. In this pioneering book, Khalilah L. Brown-Dean moves beyond the headlines to examine how contemporary controversies emanate from longstanding struggles over power, access, and belonging. Using intersectionality as an organizing framework, she draws on current tensions such as voter suppression, the Me Too movement, the Standing Rock protests, marriage equality, military service, the rise of the Religious Right, protests by professional athletes, and battles over immigration to show how conflicts over group identity are an inescapable feature of American political development. Brown-Dean explores issues of citizenship, race, ethnicity, gender, sexual identity, and religion to argue that democracy in the United States is built upon the battle of ideas related to how we see ourselves, how we see others, and the mechanisms available to reinforce those distinctions. Identity Politics in the United States will be an essential resource for students and engaged citizens who want to understand the link between historical context, contemporary political challenges, and paths to move toward a stronger democracy.

Khalilah L. Brown-Dean is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Quinnipiac University.

List of Tables, Figures and Illustrations

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1: The Personal is Political

Chapter 2: Identity Politics and the Boundaries of

Belonging

Chapter 3: The Substance of U.S. Citizenship

Chapter 4: Racial Identity, Citizenship, and Voting

Chapter 5: Ethnic Identity: Demography and

Destiny

Chapter 6: Gender, Sexual Identity, and the

Challenge of Inclusion

Chapter 7: Religious Identity and Political Presence

Chapter 8: Identity and Political Movements

Chapter 9: The Inescapability of Identity Politics

Glossary

Works Cited

Notes

?Brown-Dean makes clear how notions of belonging and exclusion constitute relentless forces in shaping policy, laws, and political representation in the United States. The book?s lively interplay of deep historical dives and compelling empirical evidence drives home the power of boundary-making around race, gender, religion, and other identities in US political life. A must-read for students of politics.?

Janelle Wong, University of Maryland

?Brown-Dean situates today?s identity politics debates within a much-needed legal and political historical context, revealing that all politics are indeed about identity, and urging us to resist simplistic frameworks and instead engage in tough but necessary conversations about difference.?

Heath Fogg Davis, Temple University

?An exciting and comprehensive introduction to identity politics in America today.?

Sharon Wright Austin, University of Florida

?This superb text is masterfully written and excellently researched. Undergraduate students will find the material engaging and thought-provoking. Professor Brown-Dean is skilled at making the basic tenets of American government come alive in the 21st century by foregrounding identity politics as central to understanding American democracy.?

Nadia Brown, Purdue University

1

The Personal is Political

I first discovered the work of poet and essayist Maya Angelou in middle school. Even though the themes in I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings were mature, I felt a deep connection to the story she told of growing up in Stamps, Arkansas. I flinched when she recounted being raped by her mother’s boyfriend. I cried when Uncle Willie hid in the potato bin to avoid the Ku Klux Klan. Klan leaders throughout the United States included sheriffs, judges, prosecutors, and ministers. It seemed ominous that the very people responsible for protecting vulnerable communities routinely engaged in terrorizing them.

Maya Angelou’s voice let me know that it was OK to be a little brown girl with a big Arabic name in a place called Lynchburg, Virginia, with the audacity to imagine possibilities unbound by geography. I vowed to someday thank Dr Angelou in person for inspiring me. At seventeen I finally had the chance – or so I thought. That year Angelou arrived at my high school as part of a citywide Black History Month observance. I was selected as one of the students who would get to speak with her. Being a nerd has its perks. I rehearsed what I would say to her a thousand times. I was determined not to come across as some naïve kid in search of an autograph. With dog-eared copy of my notebook in hand I patiently waited for my turn. But I was awe-struck. The words simply wouldn’t come. Angelou looked at me and said with that beautiful, commanding lilt, “Would you like to say hello?” I eagerly shook my head and squeaked out, “Hello?!” She smiled and took the time to nod her reassurance. I knew in that moment she realized the impact she had on me. Angelou was my intellectual rock star.

Quite literally, Angelou made it possible for me to be the first person in my immediate family to earn a four-year degree. I competed in oratorical competitions in high school and earned college scholarships using a number of her poems and essays. I discovered the poem “Our Grandmothers” while trying to understand why the contributions of women were so overlooked in the retelling of American freedom movements. I knew about Harriett Tubman and could recite Sojourner Truth’s “Ain’t I a Woman” line by line. But “Our Grandmothers” highlighted the ways that everyday acts of resistance challenge exclusion. It is a beautifully complex poem that affirms the power of women who make personal sacrifices to inspire, protect, challenge, and build communities. I have always been struck by a line from it that reads “When you get, give. And when you learn, teach.”

Dr Maya Angelou was a poet, performer, and essayist. She delivered a poem at the 1993 inauguration of President Bill Clinton and received the 2011 Presidential Medal of Freedom.

I grew up in a town where the specter of Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority movement loomed large. The Moral Majority was a concentrated effort in the 1980s to raise the political voice of the Christian Right. Despite my Southern Baptist upbringing, it didn’t make sense that one minister could convince local government officials to change the day my friends and I would trick or treat when Halloween fell on a Sunday. I looked to Angelou’s prose to give me the strength to speak before our city council to protest moving a busy fire station to the heart of our working-class neighborhood. I wondered why the demands of our neighbors weren’t enough to convince the board to change its decisions. Where was our power?

When Maya Angelou passed in 2014, a reporter asked me to choose my favorite work. At first it seemed like an impossible task, and then I remembered her essay titled “The Graduation.” Angelou reflects on her 1940 graduation from high school and paints a clear picture of how separate education is inherently unequal. She talks about the tattered textbooks and outdated science equipment that she and her classmates shared, while students at white schools had more equipment than they could actually use. Black graduates were expected to bring honor to their communities by becoming athletes, janitors, and entertainers. White graduates were encouraged to become physicians, lawyers, and teachers. Even then, the lens of identity was incredibly narrow. It didn’t matter that Angelou and her classmates had memorized Shakespeare’s “The Rape of Lucrece” or could recite “Invictus” with great conviction. Their destiny was predetermined. The name of schools for Black children in the South reinforced a sense of inferiority: training schools. I remember seeing my maternal grandmother’s class ring inscribed with “Amherst County Training School” and wondering why it wasn’t called a “high school.” In the 1940s, Black students were trained to serve society. White students were educated to shape it. That one essay helped me understand the necessity of the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision better than any legal or historical text I have ever read. Sixty years later we are still trying to figure out how to educate students equally.

I lacked the language of intersectionality at the time, but I knew these disparate experiences were bound together by a tradition of treating groups differently based on their perceived worth. In her seminal work “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color,” Kimberlé Crenshaw (1991) cautions that “the problem with identity politics is not that it fails to transcend difference, as some critics charge, but rather the opposite – that it frequently conflates or ignores intra group differences.” My neighborhood friends and I learned that lesson every morning as we passed three elementary schools en route to the suburban school we were chosen to integrate. We didn’t fully understand why we had to take the long bus ride to Paul Munro Elementary School instead of the short walk to Garland Rhodes. We dreaded the mandatory neighborhood walking tours with our teachers and classmates because it reminded us that we were perpetual interlopers. Our classmates would pass through familiar streets, pointing out their expansive homes and eagerly waving to neighbors heading to lunch at the country club, where people who looked like us were not allowed to join. Four years of field trips and the streets never felt familiar or welcoming to us. Those barriers, both real and imagined, made it clear that the meaning of our presence in multiple spaces was structured by interlocking systems related to education, religion, region, class, gender, and race. But it wasn’t just our personal experiences of being bussed to new schools or observing Halloween. It was a collective experience shared by various groups navigating identity politics in the United States.

Why This Book?

This book grows out of that interest fueled decades ago in Virginia. Democracy in the United States is built upon the battle of ideas related to how we see ourselves, how we see others, and the mechanisms available to reinforce these distinctions. To some the term identity politics has become a pejorative term used to decry the tendency to promote group solidarity at the expense of mutual progress. I reject this description because it is often lobbed against groups whose relationship to traditional spheres of influence and inclusion remains tenuous. Understanding lived political experiences across multiple identity markers isn’t an attempt to create a hierarchy of oppression based on who has suffered the most or who is entitled to the greatest political rewards. That approach is both intellectually lazy and fundamentally uninteresting. The solution, however, isn’t to tell people to strip away the layers of their identity or to ignore how those layers structure opportunities. The notion that people should stop talking about or stop affirming the groups to which they belong is inconsistent with the longstanding political practice of creating and reinforcing identity-based cleavages in US politics.

Consider, for example, contemporary efforts to address the growing opioid crisis sweeping the United States. President Donald J. Trump has declared a public health crisis as advocates argue for a kinder, gentler approach to addiction that promotes rehabilitation and support over punishment and incarceration. Some question why this new approach to opioid addiction varies from the 1990s political response to the crack epidemic that mostly ensnared Blacks and Latinos in urban areas, who were demonized as morally reprehensible (Forman 2018; Alexander 2010; Fortner 2015; Muhammad 2011; Hinton 2016). Indeed, the former mayor of Baltimore (Kurt Schmoke) was ridiculed for suggesting that addiction should be treated as a public health crisis rather than simply a criminal justice problem.1 Since the War on Drugs was formally launched in the 1970s during the Nixon administration, over $50 billion has been spent to significantly increase the arrests, prosecutions, and incarceration of millions of people in the United States. The result hasn’t made the country safer, nor has it significantly reduced addiction (Mauer and King 2007; Hart 2013). Instead, this massive collection of public policies has had a disproportionate impact on certain groups, even if members of those groups don’t perceive it as “their problem.” That type of divide makes it important to address and understand identity politics rather...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 20.9.2019 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung ► Staat / Verwaltung |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung ► Vergleichende Politikwissenschaften | |

| Schlagworte | American Politics • Cultural Studies • Kulturwissenschaften • Political Issues & Behavior • Political Science • Politik • Politik / Amerika • Politikwissenschaft • Politische Fragen u. politisches Verhalten • Race & Ethnicity Studies • Rassen- u. Ethnienforschung • USA /Politische Theorie, Geschichtsschreibung |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5095-3882-8 / 1509538828 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5095-3882-9 / 9781509538829 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich