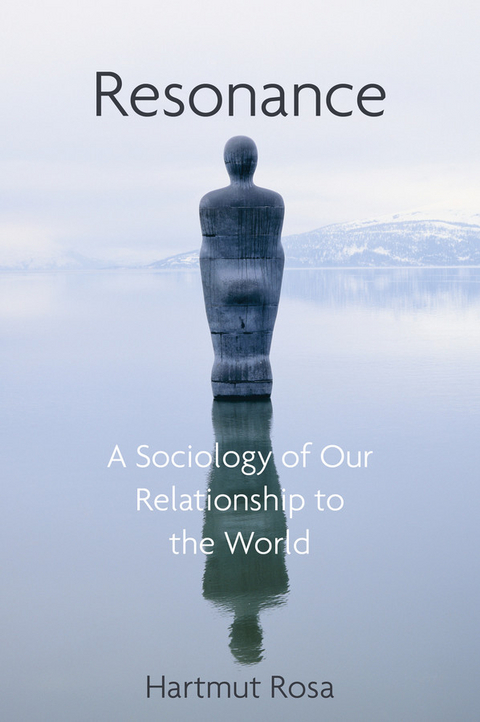

Resonance (eBook)

450 Seiten

Wiley (Verlag)

978-1-5095-1992-7 (ISBN)

Hartmut Rosa is Professor of Sociology at the Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena, Germany, and Director of the Max Weber Center for Advanced Cultural and Social Studies, Erfurt, Germany.

Acknowledgments xii

In Lieu of a Foreword: Sociology and the Story of Anna and Hannah 1

I Introduction 17

PART ONE: THE BASIC ELEMENTS OF HUMAN RELATIONSHIP TO THE WORLD

II Bodily Relationships to the world 47

III Appropriating World and Experiencing World 83

IV Emotional, Evaluative, abd Cognitive Relationships to the World 110

V Resonance and Alienation as Basic Categories of a Theory of Our Relationship to the World 145

PART TWO: SPHERES AND AXES OF RESONANCE

VI Introduction: Spheres of Resonance, Recognition, and the Axes of Our Relationship to the World 195

VII Horizontal Axes of Resonance 202

VIII Diagonal Axes of Resonance 226

IX Vertical Axes of Resonance 258

PART THREE: FEAR OF THE MUTING OF THE WORLD: A RECONSTRUCTION OF MODERNITY IN TERMS OF RESONANCE THEORY

X Modernity as the History of Catastrophe of Resonance 307

XI Modernity as the History of Increasing Sensitivity to Resonance 357

XII Deserts and Oases of Life: Modern Everyday Practices in Terms of Resonance Theory 367

PART FOUR: A CRITICAL THEORY OF OUR RELATIONSHIP TO THE WORLD

XIII Social Conditions of Successful and Unsuccessful Relationships to the World 381

XIV Dynamic Stabilization: The Escalatory Logic of Modernity and Its Consequences 404

XV Late Modern Crises of Resonance and the Contours of a Post-Growth Society 425

In Lieu of an Afterword: Defending Resonance Theory against Its Critice -- and Optimism agaibst Skeptics 444

Notes 460

References 504

Index 529

"If in the rush to increase production and wealth, we ever pause to consider what a good life would be like, and whether we're missing something essential, Rosa's book Resonance would be a good place to start. This remarkable work combines systematic theory with a host of valuable insights into human fulfillments that we too easily forgo."

--Charles Taylor, McGill University

"Affirmation of ordinary life is a key feature of modernity, but alienation from the world is a persistent experience of modern men and women. In Resonance, Rosa offers sketches of an alternative relation to the world and thereby a foundation for a sociology of the good life. A very important text and highly recommended."

--Miroslav Volf, Yale University

"Hartmut Rosa is one of the leading and most distinctive voices in contemporary social theory. In Resonance he continues the important analysis of the very nature of modernity laid out in Social Acceleration, and offers a new approach to basic human relationships, both to other people and to the world. This is a truly important book."

--Craig Calhoun, Arizona State University

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 26.7.2019 |

|---|---|

| Übersetzer | James C. Wagner |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung ► Politische Theorie |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie ► Allgemeine Soziologie | |

| Schlagworte | Cultural Studies • Cultural Studies Special Topics • Gesellschaftstheorie • Kulturwissenschaften • Political Philosophy & Theory • Political Science • Politikwissenschaft • Politische Philosophie • Politische Philosophie u. Politiktheorie • Social Theory • Sociology • Soziologie • Spezialthemen Kulturwissenschaften |

| ISBN-10 | 1-5095-1992-0 / 1509519920 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-5095-1992-7 / 9781509519927 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 1,8 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich