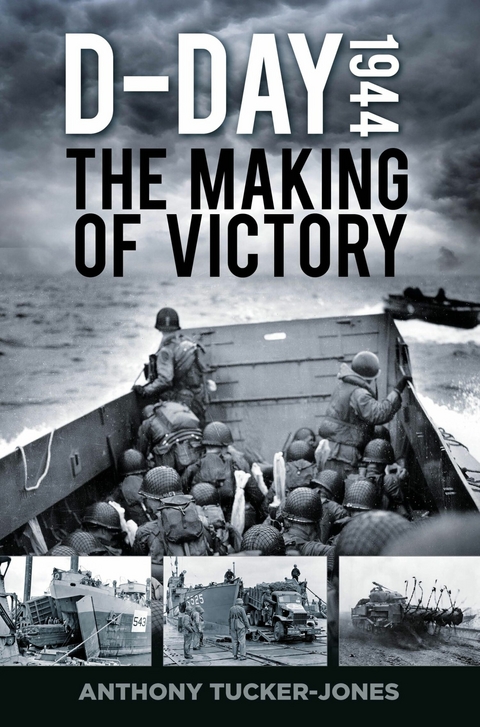

D-Day 1944 (eBook)

320 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-0-7509-9173-5 (ISBN)

ANTHONY TUCKER-JONES spent nearly twenty years in the British Intelligence Community before establishing himself as a defence writer and military historian. He has written extensively on aspects of Second World War warfare, including Hitler's Great Panzer Heist and Stalin's Revenge: Operation Bagration.

INTRODUCTION

Half-Man, Half-Beast

The roar of the powerful engines was deafening as the flat-nosed landing craft bludgeoned its way through the choppy waves. On every drop the vessel and its occupants were deluged in fine spray. The overriding smell was of diesel, oil and brine. For delicate stomachs, this and the constant motion was not a good combination. Trying to ignore these conditions, the Royal Marines slithered over their rocking tank carrying out vital last-minute checks. At sea, the five-man crew travelled on the outside just in case of mishap with their struggling vessel.

Every vehicle involved in Operation Overlord on 6 June 1944 had been plastered in a greasy, putty-like substance called Compound 219. This was jammed into all crevices and openings in a desperate effort to keep out seawater when the vehicle waded ashore. On tanks the turret ring and gun muzzle were also sealed with a type of plastic covering. Tankers did not greatly mind the application of the compound as they spent most of their time covered in grease and oil anyway. Seawater, on the other hand, was not welcome as it played havoc with the electrics and the engine. At almost 30 tons, no amount of grease would make the Centaur float in deep water.

The Marines were working on their Centaur tank, of which almost a thousand had been built. However, this was specially designed for close support and one of less than 100 armed with a 95mm howitzer destined to see action on D-Day. It was a bunker-buster that could smash open concrete at close range. The driver and co-driver gave the Nuffield-built up-rated Liberty engine one last going over. If it failed to start or stalled when the landing craft ramp went down, then there would be hell to pay.

Although its official speed was about 27mph, with a bit of doctoring it was possible to manage almost twice that. If the driver had his way, he was going to sprint up the beach at full speed, assuming that the obstacles and mines had been cleared by the engineers and the ‘Funnies’. The crew had dubbed their tank Hunter, and its turret was marked in white with the degrees of the compass in order to bring all the guns of the troop to bear on a target as quickly as possible. The centaur of ancient Greek mythology, half-man half-horse, was often depicted with a bow in its hands, so Hunter seemed highly appropriate.

The men, swerving with H Troop, 2nd Battery, 1st Royal Marine Armoured Support Regiment were heading for a beach in Normandy codenamed Gold.1 Their orders appeared simple enough: provide covering fire from their landing craft, and once they were ashore continue to assist the assaulting infantry and commandos. They had fifty-one rounds for their turret-mounted howitzer, so it was vital they made every shot count.

Amongst the Centaur crews being buffeted by the waves was George Collard. He felt that they looked suitably nautical with their ration boxes and naval hammocks lashed up behind the turret. Also, on the way over, a naval rating had taken pity on one of the crew and ‘loaned’ them a waterproof oilskin coat that was much more weather-resistant than the sleeveless leather jerkins worn by some of the crews over their overalls, which dated back to the First World War. Looking out to sea, a smile came over his face as he remembered how, earlier in the year, they had pranged the tank before it had even seen combat.

Collard’s unit had decamped from Corsham to the estate of Lord Mountbatten near Romsey in Hampshire ready for D-Day. Going through Devizes they had suffered a mishap. ‘Our tank, driven by a three-badge Royal artilleryman,’ he recalled, ‘left the road and promptly crashed through the wall.’2 The latter was inevitably a write-off, while the tank barely suffered a scratch. Besides, no one cared if the front mudguards got ripped off. It was a funny incident that resulted in much swearing by the troop commander, but such accidents were commonplace. Now, though, was the time to put all their training into practice. Lieutenant-Colonel Peskett, Collard’s regimental commander, had pushed them hard, and for good reason.

During the night, the crossing had not been pleasant for the Centaur crews, or anyone else for that matter, because of the rough sea. Thanks to the weight of the tanks, the landing craft rode very low in the water. ‘We slung hammocks where we could, sometimes between the tanks,’ recalled Collard. ‘Many were seasick, including the sailors.’3 The Royal Marines did not take seasick tablets as ‘a point of pride’.4 Being sick as a Marine was not an option. From experience, Collard had learned that the best preventative measure against feeling nauseous was to fill your stomach with hard-tack biscuits, because it acted ‘like concrete in the stomach’.5

When they neared the French coast, the Marine gunners and loaders clambered back into the turrets. They quickly rammed a high explosive round into the gun’s breech. No one liked the idea of firing a tank from a moving landing craft – least of all the coxswain. The gunners knew they were unlikely to hit anything useful, but their actions added to the general bombardment of the enemy defences nonetheless.

Aboard a tank landing craft, Sub Lieutenant Frank Thomasson, with the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve, was amazed at how relaxed the Marines were. They had risen early to check their kit and seemed in no haste to disembark. Before marching off they removed their steel helmets, and one man donned a top hat and raised an umbrella. ‘This action by the Marines had a calming effect on all,’ observed Thomasson.6 Despite seeing some of his mates killed, Royal Marine Corporal Bernard Slack did not flinch, ‘You just get on with your job. This is what you’re trained for.’7

When Collard’s troop finally rolled into the sea off Gold Beach, water rushed into the turret ring and his troop sergeant could not get out of his hatch and was soaked. Collard poked his head out the turret and ‘looked with some admiration at the sight of the shells landing on the concrete strongpoints’.8 The Germans were getting a good ‘pasting’.

Directing the sodden driver, they managed to successfully negotiate the anti-invasion obstacles, only to have the left track blown off by a mine. ‘A number of wounded and dead were on the beach,’ noted Collard, ‘including some killed where our own tanks had run over them – pushing – it appeared – the bile in the liver up to their faces.’9 Having reached the cover of the dunes, his crew managed to repair their lame Centaur and get it back into the fight.

When Sergeant John Clegg’s Centaur rolled ashore he became aware of an unwelcome noise above the racket of the engine. ‘You can hear possibly bullets,’ he said, ‘splattering against the side of the landing craft and your tank: pitter-patter, pitter-patter.’10 In response, he and his crew were soon engaging their assigned targets.

Lieutenant-Colonel Peskett had a total of thirty-two Centaurs and eight Sherman tanks with which to support the landings east of Arromanches.11 He was not a happy man though, ‘Several of my landing craft, being heavily armoured, did not weather the crossing, and either sank or turned back to land on the Isle of White.’12 From a force of ten Centaurs supporting the attack on Le Hamel, only half reached the beach and these were destroyed straight away.13

Peskett’s own ‘landing was an extremely wet one’,14 with his waterproofed jeep drowning in 4ft of water. His second-in-command, Major Mabbott, was immediately wounded and had to be evacuated. After being rescued by a passing landing craft, Peskett toyed with the idea of taking a Royal Navy bicycle ashore but instead, along with his signaller Sergeant Harris and batman-driver Marine Collis, got a lift in a half-track.

Once inland, he commandeered an abandoned Ford which had been used as a German staff car. This was a choice he was later to regret when it drew the unwanted attention of the RAF. Two days later, one of Peskett’s missing lieutenants arrived at his headquarters. When the man was asked where he had been, he responded, ‘Bayeux’. A puzzled Peskett pointed out that was impossible as they had not liberated it yet. ‘Yes, that’s what I discovered,’ said the officer nonchalantly.15

‘Hunter’ survived the landings and was photographed on 13 June 1944 rumbling along Normandy’s dusty lanes with fumes belching out of its engine. Peskett’s Centaurs were supposed to stay in Normandy for a maximum of seven days, but instead they fought for three weeks until they were broken down and had run out of ammunition. Like their mythological predecessors, they died in battle.

The Centaur tank was just one of the many ‘mechanical contrivances’16 that were the making of victory on D-Day. There were far more weird and wonderful contraptions unleashed on Normandy’s shores that day. Second Lieutenant Stuart Hills, with the swimming Sherman tanks of the Nottinghamshire Sherwood Rangers, also landed on Gold Beach. He witnessed ‘the Centaur close-support tanks …, the flail tanks and the assault vehicles of the Royal Engineers and the underwater obstacle clearance teams from the Engineers and the Royal Navy.’17 It was these that got them inland.

General Eisenhower, the Allied Supreme Commander, and his staff were in awe of the unparalleled technical innovation shown in support of...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 20.5.2019 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► 1918 bis 1945 |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Militärgeschichte | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| Schlagworte | 6 June 1944 • 79th armoured division • battle for bayeux • battle for caen • battle for cherbourg • Battle for Normandy • battle for rouen • battle of rouen 1944 • bayeaux • Caen • Carentan • d-d sherman tank • Eisenhower • funnies • Gold Beach • Juno Beach • major-general percy hobart • merville battery • Montgomery • Mulberry harbour • Omaha Beach • Operation Goodwood • Operation Neptune • Operation Overlord • Pegasus Bridge • Rommel • sowrd beach • st lo • Sword Beach • the dieppe raid 1942 • the dieppe raid 1942, operation overlord, the normandy campaign, battle of rouen 1944, battle for rouen, the normandy landings, utah beach, omaha beach, gold beach, juno beach, sowrd beach, carentan, st lo, bayeaux, caen, • the normandy campaign • the normandy landings • Utah Beach • Villers-Bocage |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7509-9173-9 / 0750991739 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7509-9173-5 / 9780750991735 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 9,7 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich