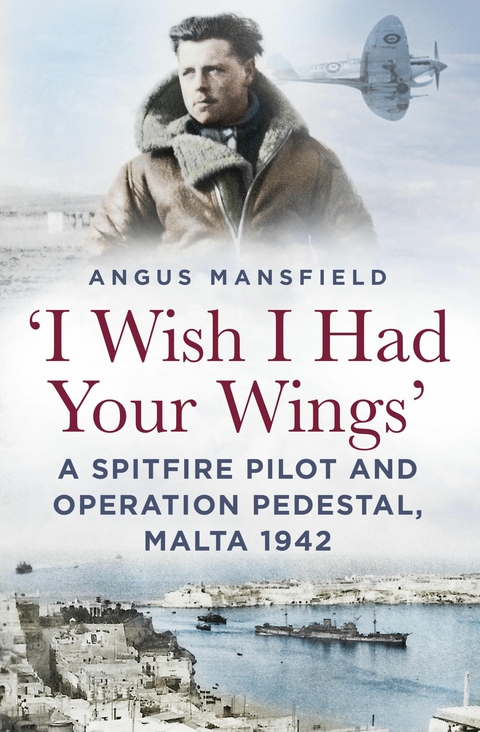

'I Wish I Had Your Wings' (eBook)

192 Seiten

Spellmount (Verlag)

978-0-7509-6688-7 (ISBN)

Angus Mansfield is the author of Barney Barnfather: Life on a Spitfire Squadron and Spitfire Saga: Rodney Scrase DFC, published by The History Press. He was educated at Wallington Grammar School and currently works in banking. He lives in Cornwall.

1

John Mejor – Early Days

John Mejor was born in Antwerp on 12 July 1921, the son of a Belgian engineer and a Scottish mother. His father died when he was only 12 and his mother brought the family to Liverpool, where, pretty much penniless, she ran a sweet shop. John was educated at Bootle Grammar School, where he had a certain affinity with the Flemish headmaster, given his Belgian origins.

Emblazoned on the school badge of Bootle Grammar School was the motto of the town of Bootle: Respice, Aspice, Prospice (look to the past, look to the present, look to the future). We must remember the past: to learn from our mistakes, to take joy from our triumphs and to honour our origins. We must consider the present: to face daily challenges, to enjoy life without taking anything for granted and to be a good example for all. We must look to the future: to build a peaceful world for the next generation, to pass on our knowledge to our children and to be hopeful that tomorrow will always bring a brighter sunrise. The motto would stay with Mejor for the rest of his life.

Rather than go to university, Mejor enlisted in the RAF Volunteer Reserve at the age of 18 in the summer of 1940, at the height of the Battle of Britain, when there was such a shortage of pilots, and began his flying training at No. 22 Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS) Cambridge, completing it at No. 8 Service Flying Training School (SFTS) Montrose in Scotland.

Those passing simple examinations left for flying training. Some went to the United States or the Commonwealth, while the remainder were shared between Elementary Flying Training Schools, with No. 22 at Cambridge, using the Miles Magister and Tiger Moth trainers and a unit operated by Marshalls Ltd of Cambridge using civilian instructors in RAF uniform, where his aptitude for pilot training was assessed and considered suitable. They lived in requisitioned houses just outside the airfield, with very basic amenities and poor food. They did their day flying training at Bottisham airfield, about 5 miles east of Cambridge, sharing it with an Army co-operation unit of Tomahawks. Mejor had only been there a few days when he saw a Tomahawk do a flat spin that went in nose first. He was told the pilot lived but lost both his legs.

The course at Cambridge lasted about two months and formed the first of three parts of their flying training, which would take about six months in all, at the end of which, in theory, they would be ready to join an operational squadron. They were supposed to do a minimum of about 50 hours of flying in each element or at each training school, but flew in atrocious conditions much of the time. Low cloud, poor visibility and high winds were not unusual and gave him a good grounding.

He then reported to No. 8 Service Flying Training School at Montrose. Formed on 1 January 1936 at Montrose in No. 23 Group, it was transferred to No. 21 Group on 1 January 1939 and renamed No. 8 Service Flying Training School on 3 September that year. It was equipped with Harts and Oxfords for both single- and multi-engine training, but on 24 June 1940 it was re-classified as a single-engine (Group 1) school flying the Miles Master. All flying schools in existence prior to the start of the war were re-designated Service Flying Training Schools at the outbreak of war.

The Master was the newest of the RAF’s advanced trainers, having been introduced shortly before the war. It was similar to the Hawker Hurricane in looks but not in performance. The Master was fitted with a Kestrel engine of some 75hp, so getting airborne was spectacular because of the kick from the extra power, and the aircraft swung due to the engine torque before it lifted into the air. Mejor quickly had to master the handling characteristics and technique required to get the best out of the aircraft. He practised straight and level flying, climbing, gliding, stalling – being wary of the sudden drop of the nose with the resultant loss of height, which was much more than he was used to – and then more practice, medium turns, take-off into wind, powered approaches and landings. It was the surge of power that he remembered.

The Wings examination proved straightforward and he was awarded his Wings on 9 July 1941.

A couple of weeks later, Mejor was posted to No. 7 Operational Training Unit at Hawarden, a few miles from Chester, where he would learn to fly Spitfires. Prior to the Second World War, aircrew completed their operational training on their squadrons, but once war had broken out and operations had begun, it became obvious that this could not be carried out by units and/or personnel actively engaged on operations. At first, squadrons were removed from operations and were allocated the task of preparing new pilots and/or crews, but before long these training squadrons were re-designated Operational Training Units. Over the next month, Mejor concentrated on formation flying, dogfighting, aerobatics and circuits and bumps, together with firing his guns and practice interceptions. By 10 November he had completed the final leg of his training at No. 57 OTU and his course was finished. Assessed as average, he was posted to the newly forming 132 Squadron at Peterhead on the North Sea coast of Scotland, 30 miles north of Aberdeen. Initially they were equipped with Mk I Spitfires but soon moved up to the Mk II, and by early 1942 to the Mk V. The 132 Squadron was a cosmopolitan squadron, with Mejor from Belgium, a couple of Canadians – Bill MacRae and Wally McLeod – and Free French, Polish and one Czech pilot, as well as a Rhodesian and of course a few British, including the flight commanders and their new squadron leader, Alfie W. Bayne DFC.

All the Canadians were eventually posted out, and the Free French and Polish pilots (with whom Mejor had a particular affinity, given his Flemish background) became part of their own national squadrons. For the eight months he was with 132 Squadron, it never left Scotland and not a single gun was fired in anger. The only time they saw an aircraft with black crosses was one day in November when a Junkers Ju 88 popped out of low cloud, dropped a string of bombs on the camp, killed one pilot on the ground with machine-gun fire and escaped into cloud without being detected by radar, leaving them questioning the reliability of their low-level radar. It was guarding against this kind of hit-and-run attack that had them frequently scrambled, in pairs during the day and singly at night, to intercept anything approaching from the east without a functioning IFF (Identification, Friend or Foe), the early transponder. Everything they intercepted turned out to be friendlies, all with their IFF off. They were a mixed bag, from Whitleys to, on one occasion, an early B17 in RAF markings.

No. 132 Squadron, winter 1942. (J.G. Mejor)

Pilot officers Arthur Russell, John Mejor and Bugs Burgess, 132 Squadron, 1942. (J.G. Mejor)

Hit-and-run raids usually took advantage of low cloud cover, ideal for the Germans but not for the RAF. It has been said that Scotland is second only to the Aleutian Islands for bad flying weather, at least in winter, and the locals claimed that this was the worst winter in living memory. When the runways were not snowed in, it was routine to be scrambled into ceilings as low as 300ft. With no navigational radio, they depended on radar to vector them back down out of cloud, preferably over the sea. From there they were on their own. None of them had had any previous actual instrument time, only dual under the hood, and none in Spitfires. They were ill-prepared to quickly become virtual all-weather interceptors and paid the price. In a very short time at least six pilots were killed, about 25 per cent of the squadron. Two spun in out of cloud; two collided in cloud; one missed the field and hit the mountains not far to the west. Another, on a night scramble, failed to acknowledge repeated orders to return to base and was last seen leaving the radar screen in the direction of Norway, which he had insufficient fuel to reach.

There were also lighter moments. Many RAF fields were designed like an overturned saucer, probably to improve drainage, so that on landing the Spitfire always ended up going downhill. At low speed, the Spitfire’s rudder was ineffective and without a steerable tail wheel, differential braking was needed to steer. Loss of brakes could mean trouble. One night Bill MacRae landed a bit long, probably overused the brakes to slow down, and they faded. He switched off and sat helpless as the Spitfire slowly rolled downhill, veering toward the side of the runway. First one wheel dropped off into the mud, swinging the machine around, so the second wheel followed. The tail rose high but dropped back before the propellor could hit the ground. He was lucky, but several others were not. Paul, one of three Free French pilots they had, lost his brakes one night and ran off the end of the runway. When they got to him, his aircraft was balanced, vertically, with the spinner and propellor imbedded in the mud. Paul was looking down at the ground from his lofty perch, repeating over and over ‘sheet, sheet’, to everyone’s great amusement.

The boredom and monotony of operations in the middle of winter in Scotland led Mejor to answer a call for volunteers for a special operation involving ‘hazardous service’, with no idea of what it would be. He boarded a train to Glasgow, then to Greenock, from where a van transported him to a well-guarded wharf, whereupon he set eyes on the huge form that he later learnt to be the American aircraft carrier USS Wasp. This massive ship was there courtesy of President Roosevelt, being his answer to Winston Churchill’s urgent plea for help with the transport of...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 7.1.2016 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Briefe / Tagebücher | |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik | |

| Natur / Technik ► Fahrzeuge / Flugzeuge / Schiffe ► Luftfahrt / Raumfahrt | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► 1918 bis 1945 | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Militärgeschichte | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| Technik ► Fahrzeugbau / Schiffbau | |

| Technik ► Luft- / Raumfahrttechnik | |

| Schlagworte | allied base • August 1942, operation pedestal, supplies, Malta, allied base, axis blockade, axis bombers, axis submarine, axis e-boats, axis minefields, merchant vessels, malta grand harbour, spitfire pilot, sea captain, captain david macfarlane, mv Melbourne star, david major, convoy, log books, letters, papers, • axis blockade • axis bombers • axis e-boats • axis minefields • axis submarine • captain david macfarlane • convoy • david major • i wish i had your wings|August 1942 • Letters • log books • Malta • malta grand harbour • merchant vessels • mv Melbourne star • Operation Pedestal • Papers • RAF 100 • sea captain • Second World War • second world war, world war two, world war ii, world war 2, ww2, wwii, • second world war, world war two, world war ii, world war 2, ww2, wwii, RAF 100 • second world war, world war two, world war ii, world war 2, ww2, wwii, RAF 100, i wish i had your wings • Spitfire pilot • Supplies • World War 2 • World War II • World War Two • ww2 • WWII |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7509-6688-2 / 0750966882 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7509-6688-7 / 9780750966887 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 5,2 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich