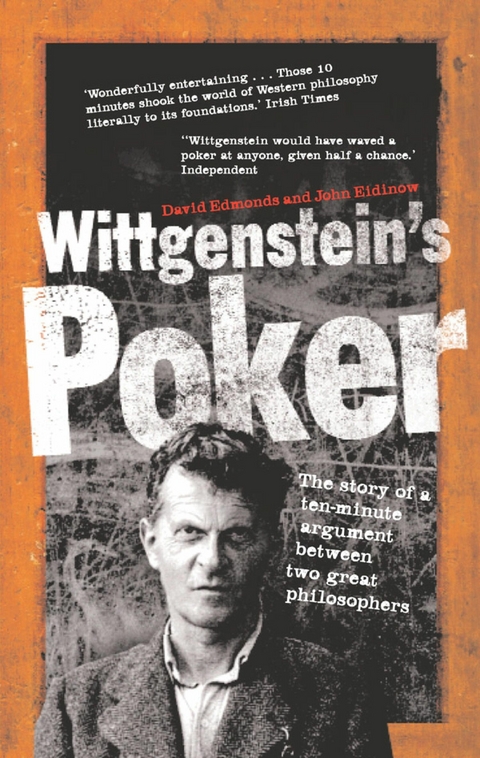

Wittgenstein's Poker (eBook)

288 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-32032-5 (ISBN)

David Edmonds and John Eidinow

On 25 October 1946, in a crowded room in Cambridge, Ludwig Wittgenstein and Karl Popper came face to face for the first and only time. The encounter lasted only ten minutes, and did not go well. Almost immediately, rumours started to spread around the world that the two philosophers had come to blows, armed with red-hot pokers . . .

Memory: ‘I see us still, sitting at that table.’ But have I really the same visual image – or one of those that I had then? Do I also certainly see the table and my friend from the same point of view as then, and not see myself? – Wittgenstein

The Gibbs Building of King’s College is a massive, severely classical block, constructed of white Portland stone. It was designed in 1723 by James Gibbs, who was the college’s second choice: the initial plan, by Nicholas Hawksmoor, one of the premier architects of the day, was too expensive, and the building’s remarkable and much praised restraint in decoration was the result of King’s being short of money.

Viewed from the street, Ring’s Parade, H3 is on the right-hand side of the building, on the first floor. The echoing approach, up a flight of uncarpeted wooden stairs past bare walls, is chill and uninviting. The double front door leads directly into the sitting room. Two long windows with window seats overlook the spacious elegance of the college front court and, filling the view to the left, Henry VI’s great limestone chapel, a supreme example of perpendicular architecture. In the silence of an October evening, the singing of King’s celebrated choir will break in on donnish concentration.

The feature of H3 at the heart of this decades-long quarrel, the fireplace, is enclosed by a marble surround above which is a carved wooden mantelpiece. It is a small, black, iron affair – more The Road to Wigan Pier than Brideshead Revisited. To its right are the doors to two smaller rooms. With views over the big lawn sweeping down to the river Cam, at the time of the meeting they were a study and a bedroom, although the bedroom has since been turned into a second study. In those days and for some years after, most members of Cambridge colleges – undergraduates and fellows alike – were expected to dart in their dressing gowns across the courts to a communal bathroom.

In 1946 the splendour of the Gibbs Building’s exterior was not reflected in the state of its rooms. This was barely a year after the end of the Second World War. Blackout curtains were still hanging – a reminder of the Luftwaffe’s recent threat. Paintwork was chipped and grimy, the walls in urgent need of a wash. Although its tenant was a don, Richard Braithwaite, H3 was just as neglected as the other rooms in the building, squalid, dusty and dirty. Heating was dependent on open fires – central heating and baths were not installed until after the ultra-severe winter of 1947, when even the water that collected in the gas pipes froze, blocking them – and the inhabitants protected their clothes with their gowns when humping sacks of coal.

*

Normally, despite the eminence of many of the speakers, only fifteen or so people would turn up to the Moral Science Club; significantly, for Dr Popper there were perhaps double that number. The medley of undergraduates, graduates and dons squeezed into whatever space they could find. Most of those who had been at Wittgenstein’s late-afternoon seminar, held in his barely furnished rooms at the top of a tower of Whewell’s Court – across the street from the great gate of Trinity College, where he held a fellowship – rejoined him in King’s.

Conducted twice weekly, these seminars offered students a mesmerizing experience. As Wittgenstein struggled with a thought there would be a long moment of agonized silence; then, when the thought was formed, a sudden burst of ferocious energy. Permission was granted for students to attend – but on condition that they were not there merely as ‘tourists’. On the afternoon of 25 October an Indian graduate, Kanti Shah, took notes. What did it mean, Wittgenstein wanted to know, to speak to oneself? ‘Is this something fainter than speaking? Is it like comparing 2+2=4 on dirty paper with 2+2=4 on clean paper?’ One student suggested a comparison with a ‘bell dying away so that one doesn’t know if one imagines or hears it’. Wittgenstein was unimpressed.

Meanwhile, in Trinity College itself, in a room once occupied by Sir Isaac Newton, Popper and Russell were drinking China tea with lemon and eating biscuits. On this chilly day, both would have had reason to be grateful for the draught excluders newly placed around the windows. It is not known what they talked about, though one account has them plotting against Wittgenstein.

*

Happily, philosophy appears good for longevity: of the thirty present that night, nine, now in their seventies or eighties, responded by letter, phone and, above all, e-mail from across the globe – from England, France, Austria, the United States and New Zealand – to appeals for memories of that evening. Their ranks include a former English High Court judge, Sir John Vinelott, famous both for the quiet voice with which he spoke in court and for the sharpness with which he responded to counsel who asked him to speak up. There are five professors. Professor Peter Munz had come to St John’s from New Zealand and returned home to become a notable academic. His book Our Knowledge of the Search for Knowledge opened with the poker incident: it was, he wrote, a ‘symbolic and in hindsight prophetic’ watershed in twentieth-century philosophy.

Professor Stephen Toulmin is an eminent philosopher of widely ranging interests who spent the latter part of his academic career teaching at universities in the United States. He wrote such leading works as The Uses of Argument, and is co-author of a demanding revisionist text on Wittgenstein, placing his philosophy in the context of Viennese culture and fin de siècle intellectual ferment. As a young King’s research fellow, he turned down a post as assistant to Karl Popper.

Professor Peter Geach, an authority on logic and the German logician Gottlob Frege (among many other things), lectured at the University of Birmingham, and then at Leeds. Professor Michael Wolff specialized in Victorian England, and his academic career took him to posts at Indiana University and the University of Massachusetts. Professor Georg Kreisel, a brilliant mathematician, taught at Stanford; Wittgenstein had declared him the most able philosopher he had ever met who was also a mathematician. Peter Gray-Lucas became an academic and then switched to business, first in steel, then photographic film, then papermaking. Stephen Plaister, who was married in the freezing winter of 1947, became a prep-school master, teaching classics.

Wasfi Hijab deserves a special mention. He was the secretary of the Moral Science Club at the time of the fateful meeting. No real prestige was attached to the position, he says. He cannot even remember how he came to hold it – probably a case of Buggins’s turn. His job as secretary was to fix the agenda for the term, which he would do after consulting with members of the faculty. In his period of office he succeeded in persuading not just Popper to travel to Cambridge, but also the man who brought the news of logical positivism from Vienna to England, A. J. Ayer. Ayer always found it an ‘ordeal’ to speak in front of Wittgenstein, but nevertheless replied to Hijab’s invitation by saying that he would gladly talk to the society, even though in his opinion ‘Cambridge philosophy was rich in technique but poor in substance.’ ‘That’, says Hijab, ‘shows how much he knew.’

Hijab’s Cambridge experience says much about Wittgenstein. He had arrived in Cambridge in 1945 on a scholarship from Jerusalem, where he had taught mathematics in a secondary school. His goal was to switch disciplines by studying for a doctorate in philosophy. Three years later he left with his Ph.D. unfinished. He had made a mistake fatal to his ambitions: against all advice – from Richard Braithwaite among others – he had asked Wittgenstein to be his supervisor. To general astonishment, Wittgenstein had agreed.

Hijab remembers his tutorials well. They were, when weather permitted, ambulatory. Round and round the manicured Trinity fellows’ garden they would walk: he, Wittgenstein and a fellow student, Elizabeth Anscombe, deep in discussion of the philosophy of religion. ‘If you want to know whether a man is religious, don’t ask him, observe him,’ said Wittgenstein. In his supervisor’s presence Hijab was mostly struck dumb with sheer terror; in his absence, he says, he sometimes demonstrated he was catching a spark off the old master.

Wittgenstein, Hijab now reflects, destroyed his intellectual foundations, his religious faith and his powers of abstract thought. The doctorate abandoned, for many years after leaving Cambridge he put all thought of philosophy aside and took up mathematics again. Wittgenstein, he says, was ‘like an atomic bomb, a tornado – people just don’t appreciate that’.

Nevertheless, Hijab retains that fierce loyalty to his teacher that Wittgenstein could inspire. ‘People often say that all philosophy is just a footnote to Plato,’ Hijab says, ‘but they should add, “until Wittgenstein”.’ His devotion finally had its reward. In 1999 he caused a sensation at a Wittgenstein conference in Austria when he more or less gatecrashed the programme, but was then given two extra sessions for his discourses on the master, meriting a write-up in the ultra-serious Neue Zürcher Zeitung. From Austria, Hijab moved on to the Wittgenstein Archive in Cambridge, to hold seminars there. It took him, he said, half a century to recover from...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 30.10.2014 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Philosophie ► Erkenntnistheorie / Wissenschaftstheorie | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Philosophie ► Geschichte der Philosophie | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Philosophie ► Philosophie der Neuzeit | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Philosophie ► Sprachphilosophie | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Pädagogik ► Allgemeines / Lexika | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Pädagogik ► Bildungstheorie | |

| Schlagworte | Karl Popper • Ludwig Wittgenstein • Ordinary Language Philosophy • Philosophical investigations • philosophy bites • philosophy books • Wittgenstein |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-32032-5 / 0571320325 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-32032-5 / 9780571320325 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 2,2 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich