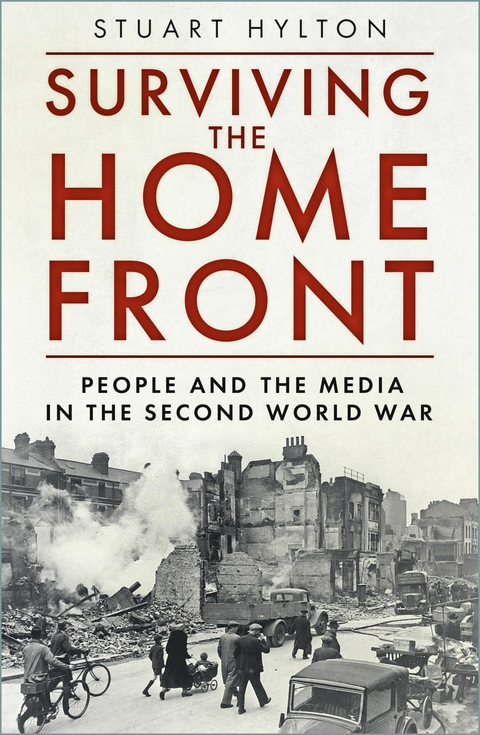

Surviving the Home Front (eBook)

310 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-0-7524-9087-8 (ISBN)

STUART HYLTON is a freelance writer, a local historian, and the author of numerous history titles including Careless Talk: A Hidden History of the Home Front, Reading at War and A History of Manchester.

2

‘Better wear a little white’: The Blackout

Two rules the walker must obey

If he would reach his home today;

On roadway always keep the right,

On footpath, just the oppo-site;

And, if by chance, he walk at night

He’d better wear a little white.

A Surrey coroner waxes poetical, after hearing the case of a pedestrian killed in the blackout, Swindon Advertiser, 13 September 1939

The blackout was introduced two days before the outbreak of war, and people were given one day to comply with its daunting requirements. As one historian of the war put it, the blackout transformed conditions of life more thoroughly than any other single feature of the war. It also gave rise to some of the most formidable regulation of the war. The Lighting Restrictions Order ran to thirty-three articles and innumerable sub-clauses that even Lord Chief Justice Caldecote described as ‘incomprehensible’.

Not everyone initially saw the need for a blackout. In the week war was declared:

A good deal of indignation was expressed to the Observer over the extinguishing of the Front Line illuminations and those at Alexandra Park, as well as the general reduction of lighting in the streets. Correspondents declared that this was creating an unnecessary atmosphere of war panic, particularly in the minds of elderly people, and this was doing as much to harm the holiday season by scaring people as the crisis itself. They argue that the lights could surely be switched off in an instant if the need arises, and it was reprehensible to aggravate an already grave situation by carrying precautions to such an apparently absurd length.

Hastings and St Leonards Observer, 2 September 1939

The Blackout Death

The blackout was responsible for many of the first casualties of the war. In December 1939 alone there were 1,155 deaths on the nation’s roads, compared with 683 the previous December. Of these fatalities, 895 occurred in the blackout. The king’s surgeon, Wilfred Trotter, was highly critical of this aspect of the blackout, claiming that by:

… frightening the nation into blackout regulations, the Luftwaffe was able to kill six hundred British citizens a month without ever taking to the air, at a cost to itself of exactly nothing.

British Medical Journal, 1940

His opposition would have had the support of the Medical Officer of Health for Swindon, who was reported as saying in January 1940 that the blackout was bad, and a cause of depression. In his judgement, the chances of being bombed were remote in the extreme. On the streets, white lines were painted down the centres of the roads, on lampposts and car running boards. One motorist was fined for failing to apply white paint to his car, despite the fact that the entire vehicle was cream coloured. Even pillar boxes were part-painted yellow (though this doubled as a gas detection measure, as the yellow paint changed colour in the presence of poison gas). One disgruntled Aylesbury resident described his newly decorated town centre as looking like ‘a blessed milk bar’. Manchester tried painting its bus stops with luminous paint, for the benefit of staff and passengers alike. Sartorial elegance became one of the first victims of the war, as men were advised to leave their shirt tails hanging out when they went walking in the blackout, in order to be more visible to motorists with dimmed lights. For those not prepared to commit this crime against fashion, the Portsea, Southsea and District Drapers’ Association (who knew a new market when they saw one) suggested white cloth armbands. Carrying a rolled-up newspaper was also suggested (not by the newspaper industry, but by a coroner, while adjudicating on the fate of someone who had failed to do so). Those who favoured wearing something white were advised by the marketing men to ensure that whatever they wore had the maximum visibility, by being whiter than white – that is, Persil-white. Luminous armbands were also introduced for pedestrians to wear.

Pedestrians who failed to make themselves visible and then got knocked down were deemed to be partly responsible for their misfortune. Leading Aircraftsman Geoffrey Allport tried to claim damages from the motorist who ran him over but the judge, hearing that he had been in military uniform at the time, told him that this made him into ‘a camouflaged object’ and dismissed the case. Pedestrians were officially warned by magistrates that it was dangerous to drink and walk in the blackout. In support they could quote the case of Marcus Woods, a soldier from Withington, who was first seen in the evening drinking in a pub, then seen falling over in the road outside – and finally found dead, covered in tyre marks. Two women in Reading were run down and killed by a bus one Sunday night. The baby they were pushing was hurled out of its pram but, by some miracle, caught by its grandfather (despite the blackout) before it hit the ground. The coroner recorded a verdict of accidental death and cleared the bus driver of all blame.

Pedestrians in Slough faced another equally lethal threat:

In the pitch blackness of the darkened streets pedestrians in Wellington Street have learned to be careful of the sentries standing on the narrow pavements outside the Drill Hall. The bayonet slopes forward just at the right height to cut the throat of any person clumsy enough to stumble into them.

Slough Observer, 8 September 1939

The very operation of bus services in the blackout was problematic. Buses could not show an illuminated display of their destination, which made it difficult at stops serving several routes to see which the right bus was. Conductors could not see to give change and there was an increase in the number of foreign coins passed to the conductors in the dark. Added to that, the passengers could not tell when to get off. The local press encouraged conductors to shout out the name of each stop as they reached it (though how they were better able than the passengers to see where they were was not explained). One additional challenge the crews were fortunately spared was having to drive a bus in the pitch darkness while wearing a gas mask, given their tendency to mist up. Silent-running electric trams had the additional problem that passengers could not always tell whether they had come to a halt, and so stepped off moving vehicles with dire results. Even worse were the fates of those passengers whose trains stopped outside the station, and who mistook a bridge parapet for the platform. Thomas Gillings of Blaydon did so and fell 20ft into the icy waters of the River Tyne. He at least managed to swim to the bank. Another man in Denham, Buckinghamshire, thought his train had stopped at Ruislip station. He was at least half right – the train had stopped. He stepped from the carriage and disappeared over the side of an 80ft viaduct, with no water to break his fall.

Motorists were equally disoriented. A common mistake was to confuse the kerb with the newly painted white lines in the middle of the road. One Wokingham motorist who made this error was surprised to find first a lamppost and then a tree in the middle of what he thought was the highway. He demolished the first and came to a shuddering halt, embedded in the second. This motorist may have been relatively unscathed, but disorientation could have far more serious consequences. The driver of an army lorry in Reading thought he was going along the main Oxford road, which ran uninterrupted through the town. In fact, he was on the road running parallel to it, which suddenly came to an unexpected halt in the form of a brick wall. In the crash which followed, two of his passengers were killed and another thirteen injured.

Passengers are asked to stop their fellow travellers falling from the train.

As petrol rationing began to bite, a new blackout problem arose in the form of increased horse traffic. The blackout regulations were silent on how to illuminate a horse (painting them white presumably was not an option – though one pet owner in Herne Bay painted white stripes on their black cat and an Essex farmer did the same with luminous paint on his cattle). But lack of regulation did not prevent a court in Basingstoke fining a gypsy who failed to provide suitable (if unspecified) lights for his horse and cart, while a court in Slough dismissed a charge against a cowman for herding unlit cattle across a road. A related issue concerned what you did with your horse if the air raid warning sounded while you were travelling. Official guidance was issued on this, but at least one householder disregarded it and shared their air raid shelter with not just the milkman but also his horse.

Nobody was safe in the blackout; the Regional Commissioner, Sir Auckland Geddes, was run down by a lady cyclist whilst inspecting ARP measures in Hastings. In coastal areas there was the added hazard of falling into the docks, making drowning a further blackout problem. This was not entirely restricted to harbours; in Pencester Gardens, Dover, they dug an air raid trench on the site of an underground spring and it spent most of its time full of water. A similar problem arose with one in London, and a 22-month-old child drowned in it. There was even a case where an elderly lady was knocked down and killed by a hurrying fellow pedestrian, prompting a campaign in the local press for pedestrians to keep strictly to the left of the pavement (assuming they could see which side was left). Doncaster was one area that actually introduced such a scheme, complete with pavement white lines.

As ever, helpful official guidance was on hand. This included closing your...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.10.2012 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Neuzeit (bis 1918) |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► 1918 bis 1945 | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Kulturgeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Militärgeschichte | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Kommunikation / Medien ► Journalistik | |

| Wirtschaft | |

| Schlagworte | newspaper archives • reporting the blitz • Second World War • The Blitz • wartime britain • wartime communities • World War Two • ww2 • WWII |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7524-9087-7 / 0752490877 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7524-9087-8 / 9780752490878 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 14,3 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich