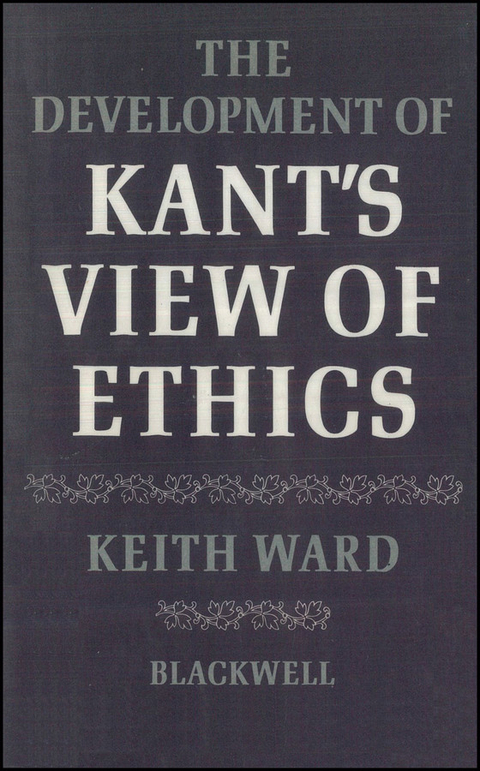

Development of Kant's View of Ethics (eBook)

376 Seiten

Wiley (Verlag)

978-1-119-59819-0 (ISBN)

This is the original 1972 text of The Development of Kant's Ethics-KeithWard's exceptional analysis of the history of Kant's ideas on ethics and the emergence of Kantian ethics as a mature theory. Through a thorough overview of all of Kant's texts written between 1755 and 1804, Ward puts forth the argument that the critical literature surrounding Kantian ethics has underplayed Kant's concern with the role of happiness in relation to morality and the significance of the tradition of natural law for the development of Kantian ethics.

Covering all of Kant's extant works from Nova Dilucidatio to Opus Postumum, Ward traces the progression of Kant's views from his early ideas on Rationalism to Moral Sense Theory and the development of the Critical Philosophy movement, and finally to his later-life writings on the relationship between morality and faith. Through careful analysis of each of Kant's works, Ward details the scientific, philosophical, and theological ideas that influenced Kant-such as the works of Emanuel Swedenborg-and demonstrates the critical role these influences played in the development of Kantian ethics.

Offering a rare and extraordinary historical view of some of Kant's most important contributions to philosophy, this is an invaluable resource for scholars engaged in questions on the origins and influences of Kant's work and for students seeking a thorough understanding of Kant's historical and philosophical contexts.

Keith Ward is Professor of the Philosophy of Religion at Roehampton University, London. His former positions have included Dean and Director of Studies in Philosophy at Trinity Hall, Cambridge; Regius Professor of Divinity at Oxford University; and lecturer of philosophy at the University of Glasgow, the University of St. Andrews, and King's College, London. He has published widely in the fields of philosophy, religion, and Christian theology.

Originally published in 1972, The Development of Kant's Ethics is Keith Ward's exceptional analysis of the history of Kant's ideas on ethics and the emergence of Kantian ethics as a mature theory. Through a thorough overview of all of Kant's texts written between 1755 and 1804, Ward puts forth the argument that the critical literature surrounding Kantian ethics has underplayed Kant's concern with the role of happiness in relation to morality and the significance of the tradition of natural law for the development of Kantian ethics. Covering all of Kant's extant works from Nova Dilucidatio to Opus Postumum, Ward traces the progression of Kant's views from his early ideas on Rationalism to Moral Sense Theory and the development of Critical Philosophy, and finally to his later-life writings on the relationship between morality and faith. Through careful analysis of each of Kant's works, Ward details the scientific, philosophical, and theological ideas that influenced Kant such as the works of Emanuel Swedenborg and demonstrates the critical role these influences played in the development of Kantian ethics. Offering a rare and extraordinary historical view of some of Kant's most important contributions to philosophy, this is an invaluable resource for scholars engaged in questions on the origins and influences of Kant's work, and for students seeking a thorough understanding of Kant's historical and philosophical contexts.

CHAPTER TWO

THE DOCTRINE OF MORAL FEELING

2.1 THE BASIS OF MORALITY IN FEELING

The earliest work in which Kant deals specifically with moral questions is the Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and the Sublime, written in 1763. Morality is not, of course, the main subject of this work, which is expressly concerned with aesthetic emotions. It seems fair to suppose, then, that one will not find in it a complete or adequate outline of Kant’s moral beliefs. But it does contain many interesting and important observations on ethics.

Kant begins by distinguishing the feelings of the beautiful and the sublime as ‘finer feelings’, which one can enjoy longer than other feelings without satiation and exhaustion; and which ‘presuppose a sensitivity in the soul, so to speak, which makes the soul fitted for virtuous impulses’. (O, 46; Ber. 2, 208.) Kant holds that ‘among moral attributes true virtue alone is sublime’. (O, 57; Ber. 2, 215.) There are also many good moral qualities which cannot be identified with ‘true virtue’, and these are characterised as ‘amiable, beautiful and noble’. Kant thus makes a clear distinction between ‘moral qualities’ and ‘the virtuous disposition’. There are many moral qualities which are valued in men. But the question of virtue, of the moral worth of the person as an agent, is quite a different question from that of whether or not he possesses these moral qualities. Thus Kant instances ‘compassion’—sympathetic concern for others—and ‘complaisance’—the desire to please—as moral qualities, but maintains that the possession of them bears no relation to the moral worth of the agent. For of themselves they may be used for immoral ends, as when sympathy for one individual blinds one to a greater but more remote duty, or when complaisance leads one to adopt immoral ways for fear of giving offence.

Further, Kant is already clear that action in accordance with virtue is not at all the same as action from virtue, i.e. action which is performed because it is right. Only the latter has true moral worth. So in the Observations he clearly sets out the central Critical doctrine that the moral worth of the agent lies only in acting from virtue.

When he comes to say what ‘acting from virtue’ is, however, he suggests ‘universal affection toward the human species’, as opposed to particular affections for particular objects. (O, 58; Ber. 2, 216.) And this he calls a ‘principle … to which you always subordinate your actions’, as opposed to a sentiment which you just happen to feel on occasion. He seems to be characterising the maxim of virtue as a feeling, though of a generalised, or universalised, kind. As such, it is, he says, ‘colder’ than more particular feelings, i.e. less intense. We may indeed cultivate ‘the universal love of man’, but it can hardly be an intense emotion; it must be a more dispassionate sentiment. Nevertheless, it is characterised by Kant as a ‘feeling’ of peculiar generality, which does not spring from speculative reason. ‘These principles [of virtue] are not speculative rules, but the consciousness of a feeling that lives in every human breast … I believe that I sum it all up when I say that it is the feeling of the beauty and the dignity of human nature.’ (Kant’s italics; O, 60; Ber. 2, 217.)

These features of beauty and dignity are central to Kant’s approach to ethics. Beauty is associated with the love of one’s fellow-men and the attraction one may feel for others. Dignity is associated with the respect for the sublimity of human nature, both in oneself and in others, which derives from man’s transcendence of empirical nature, and which finds expression in respect for others and a sense of personal honour and worth. Beauty and dignity; love and respect; attraction and repulsion, are always the two poles between which moral feeling oscillates. In the Dreams, Kant speaks of love and respect as forces of attraction and repulsion which govern the relations of beings in the spiritual world (cf. p. 37 f.). And in the Metaphysic of Morals he repeats the same idea on three occasions: ‘All the moral relations of rational beings, which comprise a principle of harmony among their wills, can be traced back to love and respect’; ‘The principle of love commands friends to come together, the principle of respect requires them to keep each other at a proper distance’; ‘When we are speaking of laws of duty … we are considering a moral [intelligible] world where, by analogy with the physical world, attraction and repulsion bind together rational beings [on earth].’ (MM, 163; Ber. 6, 488. MM, 141; Ber. 6, 470. MM, 116; Ber. 6, 449.) So it seems that Kant did not change his early view that morality was intimately associated with the feeling of the beauty and dignity of human nature.

Far from conforming to the popular caricature of a pedantic and rationalistic scholar who had little appreciation of the human sentiments, Kant always asserted that morality is closely bound up with a certain complex feeling for human nature. The problem with which he wrestled for many years was that of the nature of the relation between the ‘feeling’ and the ground or motivation of moral action. His Critical doctrine, of course, was that the moral feelings—which he cites as the feeling of pleasure in doing one’s duty and susceptibility to be moved by practical reason; the pain of conscience in violating duty; benevolent affection and reverence for law—‘lie at the basis of morality, as subjective conditions of our receptiveness to the concept of duty’. (MM, 59; Ber. 6, 399.) But they are not ‘objective conditions of morality’. It is by virtue of having the disposition to such feelings that a man is subject to obligation. But ‘moral feeling … yields no knowledge … we no more have a special sense for the [morally] good and evil than for truth’. (MM, 60; Ber. 6, 400.) Feeling is simply the subjective receptiveness in the mind to the action of practical reason; and though it ‘makes us aware of the necessitation present in the concept of duty’, consciousness of such feelings must follow, and cannot precede, the consciousness of the moral law, as it affects the mind. (MM, 59; Ber. 6, 399.) Without the susceptibility to such feelings no man could be under obligation; but the actual occurrence of the feelings ‘can only follow from the thought of the law’. Practical reason determines the moral feelings to arise in us; all we contribute is the susceptibility for such feelings, and some ability to cultivate them by contemplating the moral law itself. The feelings, once present, may give rise to moral actions; but they must be caused by practical reason, and cannot by themselves alone be the basis of moral obligations.

In 1763, however, Kant had not developed his notion of a reason which was essentially practical, and it appears that he then regarded feeling itself as the ground or incentive of virtuous action. He says, speaking of the ways in which moral motives are supplemented by non-moral motives which accomplish the same ends, ‘Since even this moral sympathy is not yet enough to stimulate inert human nature… Providence has placed within us still another feeling that… can set us in motion’. (O, 61; Ber. 2, 218.) It sounds as if feeling, specifically the feeling of ‘moral sympathy’, is here accepted as the ground of morality, which may be supplemented by other feelings to move us to moral action. And, though it is true that Kant goes on to distinguish ‘principles’ from ‘impulses’, and to affirm that the truly virtuous man must act from universal principles, nevertheless he seems to mean by ‘principle’ simply a certain unchangeability of feeling—‘the noble ground remains and is not so much subject to the inconstancy of external things’. (O, 65; Ber. 2, 221.) Thus the moral feeling is characterised by its ‘unchangeability’ and ‘universality of application’.

Kant sees that it is characteristic of virtue that its principles must be universal; that it is a matter of principle rather than of emotion; and that it is bound up with a ‘universal affection’ and ‘esteem’ for persons, or human nature. But he fails to explain that difference between the ‘universal moral feeling’ and other feelings which lies in the fact that, whereas the occurrence of feelings depends upon our sensible constitution, for which we are not responsible, the ‘love of man’ is an absolute obligation for all men. It is not enough to say, as he does, that the feeling ‘lives in every human breast’. For that would still be a contingent matter of fact. It would not, at least on his subsequent understanding of ‘obligation’, account for the obligation to have that feeling.

The Critical doctrine was to allocate this feeling to the causality of reason in its practical use, and in that way deliver it from the subjectivism which Kant attributes to all feelings. This will account for the fact that acting from virtue is acting on a principle, not just on the basis of a feeling—a fact for which Kant is unable to account adequately as long as all rational principles are attributed to speculative reason alone. In the Observations, however, Kant still seems to be committed to an account of morality in terms of feelings, and so he is unable to adhere consistently to the principle he formulates in the Prize Essay, written in the same year: ‘All the actions prescribed by ethics… cannot be called obligations, so long as they are not subordinated to a single end, necessary in itself.’ (PE,...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 18.4.2019 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sonstiges ► Geschenkbücher |

| Geisteswissenschaften | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie | |

| ISBN-10 | 1-119-59819-2 / 1119598192 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-119-59819-0 / 9781119598190 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich