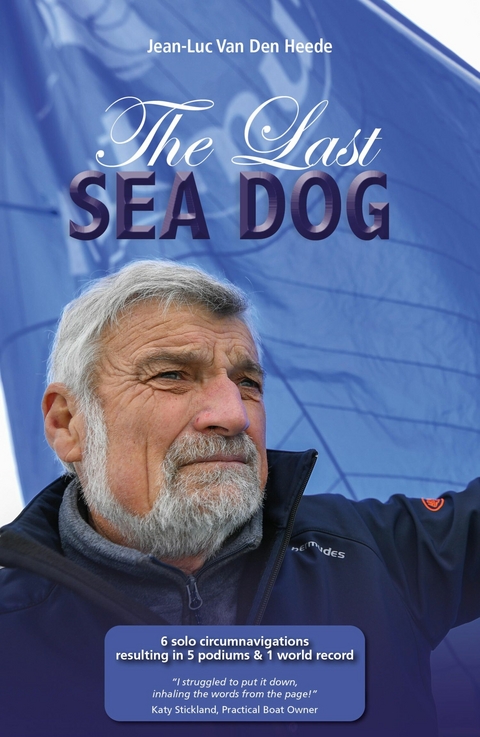

The Last Sea Dog (eBook)

200 Seiten

Fernhurst Books Limited (Verlag)

978-1-912621-97-2 (ISBN)

Jean-Luc Van Den Heede has rounded Cape Horn twelve times and completed six solo circumnavigations, achieving five race podiums and one world record (circumnavigation against the prevailing winds and currents, which he still holds). He finished third then second in the Vendée Globe, and won the retro ('as in 1968') Golden Globe Race in 2019 at the age of 73.

Chapter 1

Knock-down

With the regularity of a cathedral bell, the waves crash against the starboard side of my boat. Powerful and vicious at the same time, they are not only violent, but the noise they create inside the dark cabin, turn it into a giant, echoing drum, further increase the level of threat and stress.

I’m on high alert. My boat rocks from side to side with the relentless determination of a metronome. This is not the first time I’ve faced a storm in these vast expanses of the Southern Pacific Ocean, far from any land. I have confidence in my boat, my floating safe. Nevertheless, the situation is worrisome, and it’s only because I’m exhausted from the sleepless night before, that I manage to close one eye.

The respite is short-lived. Without warning, all at once, I’m thrown out of my bunk.

I roll and get squashed – like a fly – with all my weight (all 90 kilos of me) against a locker. Another second and I find myself stuck to the ceiling of the cabin. I’m half-conscious. Between dream and reality, I hear heaps of objects falling in an indescribable chaos and clamour, until the fridge door opens, releasing a cascade of provisions suddenly turned into projectiles.

As proof of the ferocity of this onslaught, the floor hatches, covering the batteries in the bilges, burst open despite the safety latch and the heavy bag of medical kit placed on top of them. There’s no doubt, I’ve capsized, or at least performed a serious somersault. From 130-140 degrees? Or 150 degrees? It doesn’t matter. My brave Rustler 36 was hit hard and took a blow, insidious but formidable. A real uppercut.

In an instant, the boat rolls in the opposite direction and I find myself upright again. By some miracle? The heavy keel, which represents almost half the weight of the boat on its own, played its role. Thank God. I move and regain my senses. Nothing seems to be broken, minor bruises perhaps, but no serious injuries.

In the chaos, I locate my boots and my wet weather jacket, climb on deck and peer into the darkness to see what damage has been done. The mast is still standing but the shrouds are slack and the mast rocks from side to side in the menacing Southern Pacific Ocean swells.

The canvas companionway dodger, which allows me to steer in shelter, is literally torn apart, its stainless-steel frame twisted like pieces of flimsy wire. I’m not feeling great, but I pull myself together. Now is not the time to be demoralised. I grab the flashlight at the bottom of the companionway steps and head back onto the deck for a thorough inspection.

The night is pitch black. The wind is blowing furiously. I roughly estimate the waves to be around nine metres. I hang on to my bucking bronco of a boat. ‘One hand for you, one hand for the boat’. The saying is more relevant than ever – especially since I’m not connected to any lifeline and I’m not wearing a lifejacket. I know it’s not sensible, but I didn’t have time to put it on, and anyway, in this situation, it wouldn’t be very useful since I’m alone on board, and the nearest competitor is more than two weeks away from my position.

Flashback: 48 hours earlier, the race management2 warned me about a strong storm. I even sensed some anxiety in the voice of Don McIntyre, the chief organiser of the Golden Globe Race, an old friend and seasoned sailor to whom I had lent my apartment overlooking the Bay of Sables-d’Olonne during my absence. Unlike me, he has access to all the weather forecasts, increasingly reliable and precise because of modern technology.

However, I just saw the needle of my barometer in free fall. Unfortunately, a sign (that does not lie) of bad weather to come. The radio amateurs I could speak to on my High Frequency radio, also confirmed a storm with southwest winds at Force 11 (103-117 km per hour or 64-72 miles per hour) gusting to Force 12 (over 117 km per hour, or 73 miles per hour – hurricane strength winds on the Beaufort Scale), accompanied by waves the size of a three-storey building.

I was sailing with a beam wind at about 2,000 miles (3,700 kilometres) from Cape Horn on this 5th November 2018, almost routine after 126 days of sailing since starting at Les Sables d’Olonne, France.

From time to time, a stronger and higher wave crashed into the hull and over the boat. Although Matmut is fairly stable under sail, thanks to its good beam width, I was worried but focused.

After completely lowering my mainsail, I was left with only a tiny scrap of canvas at the front. In anticipation of the worst, I made sure to secure and tie down everything that could be. However, I did need to rest as soon as possible. In a near sleep-walking state, I noted in my logbook, a 21 × 29.7cm school notebook with small squares and a red plastic cover: ‘Wind 50 knots and more, sea is frothing!’ Perhaps it was a coincidence or a premonition because for once, I left the small lamp above the chart table on and decided to lie down on the port bunk, the lee side.

My sleeping bag was damp, and my mattress as inviting as a garden bench in the rain.

The catastrophe has arrived. The long-feared capsizing and my rather eventful awakening. First assessment: The head of my Hydro vane self-steering gear, has suffered damage, but it still functions and steers my wounded vessel, which now zigzags between walls of raging water. Yes, the shrouds have loosened under the impact, and the mast has indeed been damaged at the port anchoring point of the shroud. To relieve it and potentially preserve it, I have no choice: I must position the boat in such a way to put the least side-ways strain on the mast.

This means I am steering north – the opposite direction to the route I had been following until now. I curse myself. I should have anticipated more, especially since I had a significant lead over the rest of the fleet and should not have stayed parallel to the waves for so long.3

What a fool! Now it’s over; I will have to abandon the race. To make matters worse, the depression that has just pummelled me is not willing to let go. I have no way out. I know the rules forbid me from making a phone call – risking immediate disqualification4 – but I can’t help but grab my satellite phone to reassure my partner. She’s in a meeting, but, thanks to the miracle of technology, she answers on her mobile.

I know I am breaking the Race rules, but I especially don’t want Odile to learn about my distress and troubles from a third party, a member of the GGR organisation, or worse still, from social media.

I briefly tell her that I am diverting to Puerto Montt in Chile and ask her to contact the local Beneteau dealer so that they can best organise my arrival and – and my withdrawal from the race.

I could continue my journey after repairs and compete in the Chichester Class, into which competitors drop if they have made one-stop or received outside assistance while at anchor. I don’t even consider this option for a second. Perhaps, as a beginner during my first circumnavigation, I might have set off from Chile again, but now it’s inconceivable. I would feel like I’m failing, wasting my time. This is my sixth and final solo circumnavigation race and arriving without stopping is my only goal.

Disheartened, I sit at the chart table, open my notebook, and in capital letters, with a blue pen, I write: ‘CAPSIZE! SO THERE IT IS, THE JOURNEY IS OVER!’ I no longer maintain my heading, no longer plot my course, and no longer mark any points on my soaked chart.

Time has stopped. What’s the use! I no longer consider myself part of the race and feel like an outsider. I think about selling my boat there and then, getting a flight back home as soon as possible to spend Christmas with my family. Nevertheless, I start pondering on getting a new mast sent from France and continuing my adventure outside the race. I no longer know what to do! On the edge of the storm, my mind is boiling over! For sure, the mast is damaged but my margin of safety is still reasonably comfortable.

Soon, the wind shifts to the northwest, and the sea gradually calms down. The situation isn’t ideal, but it allows me to consider some repairs. I prepare my tools and strap on a harness, the kind usually used by mountaineers. I’m no longer in my twenties. Climbing the mast is always perilous at sea, not to mention the descent.

Picture this: A still-choppy sea, swells of three metres or more, an ‘old’ man struggling to climb by sheer arm strength a telegraph pole more than ten metres high. I’ve experienced calmer situations.

I quickly confirm that the port shroud attachment has cut through the mast downwards like a can opener. The backing plate is torn off. My mast is in a sorry state. With nothing to lose, I’m going to try to stop further damage by lashing the shroud attachment to secure it from slipping down further.

I climb up again a second time, the following day, an operation that requires more than two hours of intense effort, with cramps and bruises as guaranteed bonuses because of the wildly swinging motion of the mast and the effort of holding on for dear life. I’m exhausted. I contemplate the most ingenious, or at least, the most effective solution. I need a very strong piece of rope of a few millimetres in diameter. The only piece suitable is the string of my trailing log – a device consisting of a small, spinning propeller on a long piece of rope, towed behind the boat. The number of times the propeller revolves is...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 5.11.2024 |

|---|---|

| Reihe/Serie | Making Waves |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport ► Segeln / Tauchen / Wassersport | |

| Schlagworte | cape horn • Chichester • Circumnavigation • Don McIntyre • Golden Globe • Knox-Johnston • Moitessier • round the world • Slocum • Tabarly • Vendée Globe |

| ISBN-10 | 1-912621-97-5 / 1912621975 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-912621-97-2 / 9781912621972 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 5,4 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich