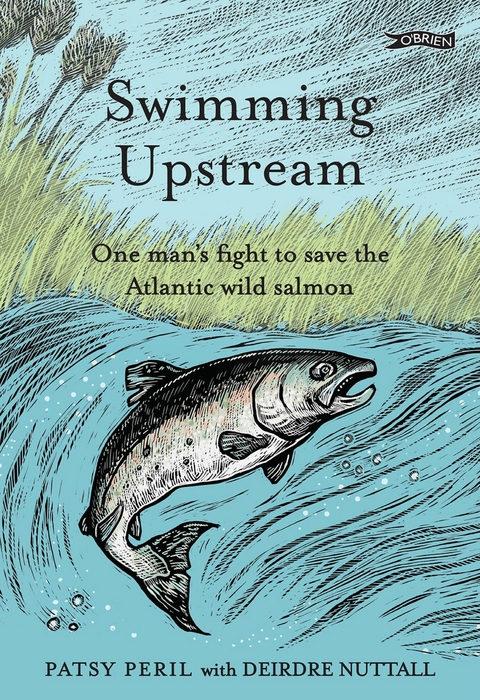

Swimming Upstream (eBook)

248 Seiten

The O'Brien Press (Verlag)

978-1-78849-545-5 (ISBN)

Patsy Peril grew up in the fishing community of Coonagh, on the outskirts of Limerick City. Involved in inland fisheries all his life, he is also an experienced light aircraft pilot. He has been deeply concerned with environmental matters since childhood, in particular concerning the health and future of Irish rivers. For decades, he has been involved in organisations involved with the oversight, protection, reclamation and sustainability of our natural environment, as well as both local and national salmon net fishers' associations. Patsy continues his activism, striving for a time when our natural waterways are respected and cared for, and for a healthy and sustainable balance between the uses of our environment and its wellbeing. A frequent contributor to meetings, conferences and congresses, Patsy is now ready to bring his crucial message to a general readership.

In December 1922, the Irish Free State was born, and in May 1923, the Civil War that followed independence came to an end. The new nation had plenty of pressing matters to attend to: the rebuilding of central Dublin; the healing of communities that had been torn apart; the development of a land that was then one of the poorest areas of western Europe; and the fostering of a sense of nationhood among a traumatised population, to mention just a few.

One urgent issue was electrification. Ireland lagged far behind the rest of western Europe and much of the developed world in this respect. Most rural and many urban and suburban areas still had no electricity. Without a modern network, Ireland would remain unable to industrialise and develop. We would forever be dependent on Britain, which was then by far our biggest export market, as well as a major destination for enormous numbers of Irish people who emigrated and migrated every year in search of opportunity.

At that time, in those parts of Ireland that did have electricity, it was largely provided by small private suppliers, about 300 in total. Roughly three-quarters of the nation’s electricity was used in the Dublin area.1 Many rural people had never experienced electricity at all, and could hardly imagine its potential to change the way they lived. At a glance, it was not at all obvious how Ireland was going to turn this situation around. While many other countries relied chiefly on coal-burning power stations, and had their own mining industries to provide the precious fuel, Ireland had no coal reserves, and had always relied on imports from Britain. But there were other possibilities, notably the vast energy embodied by the River Shannon, one of the largest rivers in Europe, vast and deep and wide and full of largely untapped potential.

The Shannon is by far the biggest river in Ireland, 360 kilometres long with a catchment area estimated to amount to about one-eighth of the country. It flows through Lough Allen, Lough Ree, and Lough Derg on its way to the sea near Limerick. The Shannon Estuary with its brackish water, subject to the movement of the tides, extends over 100 kilometres inland. Talk of harnessing the power of the Shannon had been ongoing since the early nineteenth century, but nothing had been done about it.

In 1835, CW Williams addressed the British parliament, referring to the remarkable poverty of many Irish in the western part of the country – ‘absolutely wanting the necessaries of life, and driven to desperation’; ‘miserable people’ – and the pattern of huge numbers migrating to Britain for work. Williams pointed out that the Shannon, the largest river in Britain and Ireland, remained undeveloped and had the potential to utterly transform the fortunes of the western half of Ireland. He further said that the waterways of Canada – still a British colony and much more distant from the centres of power than Ireland – were comparatively well-developed.2 The Shannon was an important transport artery and fishery throughout the nineteenth century, and it clearly had potential for much greater exploitation.

Nothing much happened in the following decades, and the extraordinary levels of poverty and emigration witnessed by Williams would – shamefully – remain a feature of life in the western parts of Ireland for generations to come, persisting well into my own lifetime.

In the early 1920s, a young Irish electrical engineer called Thomas McLaughlin was working in Germany, then a leader in the development of complex engineering infrastructures. Thomas studied all the options on the table for the electrification of Ireland, and determined that the power of the River Shannon represented the best possible means of providing a nationwide supply of electricity. He took his ideas to the Irish government, and the government listened. Although the project was going to cost an enormous amount of money, at a time when the country’s rulers were still learning how to govern and when money was very much lacking, it decided to act decisively and quickly.

In 1924, Herr Reichard and Herr Wallem, principal engineers at the German firm Siemens-Schuckert and world experts in hydroelectricity, visited Ireland. They viewed the Shannon and spoke with Irish government authorities about how the river might be used to electrify the country.3 All of this convinced the government – in particular Patrick McGilligan, Minister for Industry and Commerce from 1925 and also an old college pal of Thomas’s from University College Dublin4 – that this was the right approach.

The Free State made an agreement with Siemens-Schuckert for the German company to oversee the creation of a vast new hydroelectrical plant with the potential to push Ireland into the industrial age and turn its fortunes around. The project would be known as the Shannon Scheme. It was so huge, so ambitious and so fascinating that, even though the country was still reeling from the recent years of violence, the very idea of it filled newspaper pages and people’s heads with astonishing new thoughts.

Critics of the Shannon Scheme – including Éamon de Valera, who was then in opposition5 – pointed out that Ireland was not an industrial country. It was relatively poor and underdeveloped, with large numbers still employed in traditional, small-scale farming, using techniques that had remained essentially unchanged since the Middle Ages. It was suggested that there really wouldn’t be great interest in electricity in rural areas and villages, and that perhaps a ready supply of electricity was not that important to Ireland, or at least not yet. Perhaps it would make more sense to leave such a major infrastructural project until Ireland had developed further, when poverty was less of an issue, and when the government had more money to invest.

Supporters of the Shannon Scheme quickly countered that there were 130 towns and sizeable villages in the country with no electricity at all. Goods that had once been made by hand in Ireland and sold locally were now being replaced by industrially produced items imported from overseas, and at a time of high emigration.6 If Ireland was to have any future at all, they argued, it needed to improve its industrial base, and the only way to do that was with a reliable source of electricity.

In 1925, the Dáil passed the Shannon Electricity Act, providing for a power plant at Ardnacrusha, near Limerick, and giving the government sweeping powers to do whatever it took to get the plant built. A contract was signed with Siemens-Schuckert in August of that year.7 It was anticipated that the scheme would have a dramatic impact on the fish living in the Shannon, but the Act made no provision for the welfare of the river’s biodiversity or the preservation of the salmon fisheries. Both were considered a price worth paying at that time, even though many communities depended on the fisheries to survive. Construction on the Shannon Scheme began in September that year.

Nowadays, before engaging in a project of this nature, it would be necessary to carry out comprehensive environmental-impact studies. The threat to the natural environment would be assessed, and steps would be detailed to mitigate against this. But in those days, no such studies were required. If they had been, though less was known then about biodiversity and conservation than now, many glitches in the operation of the service could have been avoided, and many issues that are still ongoing to this day could have been solved. While we cannot judge the people of the past by the standards of today, it is fair to say that the Irish authorities, in their rush to build the hydroelectric plant, simply bypassed elementary planning and safety compliance, even by the lower standards of their time.

In 1927, the Dáil passed the Electricity Supply Act, ‘to make provision for the transmission, distribution, and supply of electricity’.8 The Electricity Supply Board (ESB) was established to operate the Shannon Power Works and to organise a national supply of electricity,9 in what would be the world’s first entirely integrated national electricity utility.10

Having inspected various options, the electrical engineers decided to use the total fall of the hydraulic gradient from Lough Derg to Limerick. In order to capture the full potential energy of the 100-foot difference in water levels, the engineers constructed a major dam at Parteen Villa, six kilometres south of Lough Derg and Killaloe. It extends across the main Shannon River, from County Clare to Birdhill in County Tipperary. Impounding the river in this way enabled the diversion or abstraction of the water at the dam into a twelve-kilometre aqueduct race, giving a 100-foot head of water gravity to the turbines at Ardnacrusha power station. The expended water that ends up in the tail race, after the generating process, is very unlike the gentle water of the head race. In fact, the powerful forces of nature released in the process still have to be seen – and heard – to be believed.

The huge Ardnacrusha plant, constructed in reinforced concrete,11 incorporated...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 21.10.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Freizeit / Hobby ► Angeln / Jagd | |

| Schlagworte | Irish Wildlife • Preservation • River Shannon • salmon |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78849-545-4 / 1788495454 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78849-545-5 / 9781788495455 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 3,6 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich