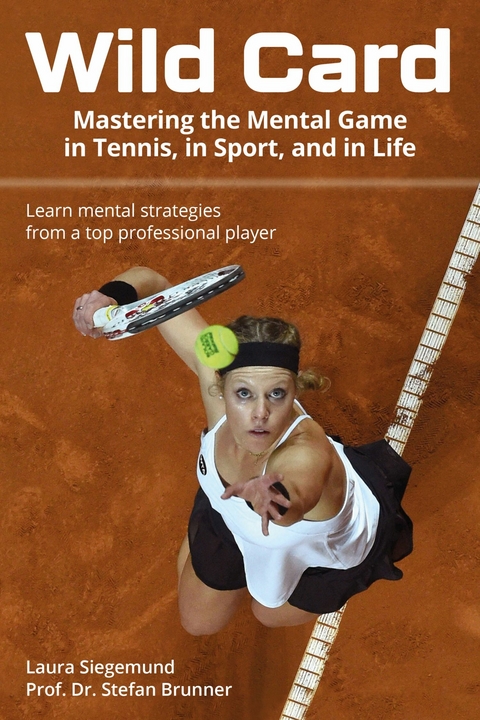

Wild Card (eBook)

271 Seiten

Meyer & Meyer (Verlag)

978-1-78255-553-7 (ISBN)

Laura Siegemund is a world-class tennis player, two-time Grand Slam winner in doubles and mixed doubles, and two-time Olympian. She holds the highest coaching license from the German Tennis Federation, has a Bachelor of Science in Psychology, and lectures in competitive sports and business companies. Laura currently resides in the United States. Prof. Dr. Stefan Brunner is a sports scientist and mental coach. He coaches high-performance athletes in various sports. He is an author, having written for many journals and scientific articles, as well as a university lecturer. He holds a doctorate in sports psychology.

Laura Siegemund is a world-class tennis player, two-time Grand Slam winner in doubles and mixed doubles, and two-time Olympian. She holds the highest coaching license from the German Tennis Federation, has a Bachelor of Science in Psychology, and lectures in competitive sports and business companies. Laura currently resides in the United States. Prof. Dr. Stefan Brunner is a sports scientist and mental coach. He coaches high-performance athletes in various sports. He is an author, having written for many journals and scientific articles, as well as a university lecturer. He holds a doctorate in sports psychology.

2

The match picks up pace

© picture alliance, Bernd Weißbrod, dpa

BREAK AND REBREAK: BEING IN THE FLOW

Serotonin, dopamine, and noradrenaline—they are jokers in our system: the happiness hormones. We must nurture them and keep them happy. And science tells us how to do so by providing us with happiness-hormone boosters: chocolate, for instance, which is only mentioned here but not elaborated on for obvious reasons. Another happiness-hormone accelerator is much more important: movement or sport, which can help us find happiness or, at least, happy moments.

Let’s take serotonin. It regulates our satisfaction gauge. When there is a sufficient amount, it binds to receptors in the brain and writes a feelgood program in the control center. We feel motivated, our mood lifts. Sports give us those moments of hormone release, not just during the glorious moment of a win, but also along the way. And on top of that, when sport is done for its own sake, we feel free of rules and goals.

•What happens to us and inside us when we are overcome by joy?

•Why does the unexpected and impressive Olympic win make us emotional?

•Why do people cry when they cross the finish line at a marathon for the very first time?

Christian Kreienbühl has conclusive answers. The two-hour-and-thirteen-minutes runner was a member of the Swiss national team, and he and his team won third and fourth place at the European Track and Field Championships in 2014 and 2018, respectively.

What are those final kilometers before the finish line like? “It’s like being a child and running barefoot down a grassy slope, knowing that your favorite ice cream is waiting for you at the bottom of the hill.”52 And when things go really well, such as when Kreienbühl won bronze at the European Championships, “then you might experience one of the most beautiful things that can happen to someone in life: crying tears of joy.”

What the European championship is to this Swiss national team runner is what the New York Marathon is to the ambitious recreational athlete. At this world-renowned race, the locals line the streets in Central Park, and they even stand several rows deep for the final kilometer on both sides. The runners and their fans don’t know each other, yet they feel close, spatially and emotionally.

The “Go, go, go!” from the spectators carries the runners across the finish line. Happiness hormones flow through the body, and potentially do so for some time. Kreienbühl tells us that his “high” lasts for two to three weeks. “During that time, I practically fly through my daily routine. Many things seem incredibly easy.”53

UNDERSTANDING THE MATCH

We can spur ourselves on, motivate ourselves, achieve highs and states of flow. It would be unfortunate and very limiting to always tie our feeling of happiness exclusively to the sense of always having to be better than the others. Because the basic concept of competition only admits very few to its winner circle.

This concept can be distilled down to a very short formula: one wins, one loses. Or slightly more differentiated: the first one wins, the second and third also win a little bit, and everyone else loses. And in some sports, even third place isn’t worth anything. Like tennis. So, it’s about a very few first places that the confusingly large horde of success-hungry athletes vie for. In other words: There are very few winners and an awful lot of losers.

That’s pretty frustrating for the non-winners, especially considering the fact that there is not much fluctuation in the group of winners, meaning it is often the same ones that raise the trophy, the Messis and Ronaldos, the Williamses, Woods, Bolts, Bradys, Gretzkys, Neuners, Grafs, and Halmichs. Changes on the winner’s podium often only occur when those who led for years slowly decline due to age.

It’s like the worldwide distribution of money. At the end of 2020, about 1 percent of the world’s population owned almost half of all the money in the world.54 This means that very few reap the fruit of their labor, in society overall and especially in the sports market segment. Beyond dispute: it’s the sport that makes it so difficult to get all the way to the top, and that ultimately the hope for success is greater than any rational forecast.

It is not a philosophical digression on the overrated question of fairness. Rather, it is about generating more satisfaction, or better yet, producing more satisfied individuals from this blatant disproportion. Or simply put:

•How can an ambitious, diligent person, and particularly a hard-working, talented athlete also find some personal gratification off the winner’s podium?

Meaning, equating satisfaction solely with the number of victories—with such a low chance of winning—is more than precarious. While winning might be a person’s ultimate goal, the journey is also of value. The arrangement must be mutually agreeable, which is also something employers and employees say when they negotiate salaries.

So, it’s not just about the salary deposited into your account at the end of the month meeting your demand. The four weeks prior to payday are also of value. This corporate concept also applies in sports and can be projected onto a match, a tournament, a season, or even an athlete’s entire sports career.

Hence, we need to think about the demands and desires with which we approach our goals. And, whether sports or athletics, it is primarily not a question of physics, but of the psyche, which organizes the system that is human as a facilitator and regulator, much like a traffic- and information network.

That’s how Paul Kunath, who established and headed the department of sports psychology at the prestigious German College of Physical Culture in Leipzig in 1961, eloquently described it.55 We must think about what it is we want in terms of our long- and short-term goals.

Win or loss. Good or bad match. Healthy or injured. Only striving for perfection, considering only the best as good enough and, if necessary, forcing it; for years, these things prevented me from tapping my full potential. And it mostly kept me from enjoying the small steps. My greatest developmental leaps forward only came when I was finally able to stop seeing everything as black or white.

It was particularly evident in my younger years; everything had to be perfect. The preparation, training, the match. Every dent in my performance or inconsistency in the process on the way to my goal felt like something unwanted, something bad. On my quest for perfection, I was nearly always disappointed. One thing is certain: the ideal of perfection is a rarity, and not only in professional sports.

My delusion regarding perfection even caused me to completely lose my joy in playing tennis, and for a while I did not play professional tennis at all. My view of perfection, performance, and success changed a lot during my hiatus.

I learned to look at my career as a whole, but also view my matches as small journeys, with their highs and lows, with which I wanted to consciously engage. With that attitude in the back of my head, I was able to play a very different kind of tennis. I still had a goal, but a different one.

Viewing our own performance and development as small stages in a journey can become a worthwhile goal and can underpin the creative process with even more meaning and satisfaction. To that end, working with everyday metaphors always proves an effective vehicle. It transports us through familiar surroundings in our imagination.

Travel is a particularly suitable parallel universe when it comes to process structure. We can accelerate when it is urgent, for instance, when the final minutes of a match must force a decision. And we decelerate when we wish to break up the rhythm or want to buy time.

And when the opponent is setting the pace? We adapt the metaphor accordingly: we briefly become the passenger and wait for the moment when we can retake control of the car to continue the trip in the direction we wish to travel.

We are essentially determined to gain the upper hand as quickly as possible. We try to dominate the rallies from the start, but also the pace and the time between rallies to control the overall atmosphere on the court, to put our own mark on the match. The opponent should feel like it’s not her match, not her court, not her day.

On the professional level, there is no time to wait and see how the game evolves. We get down to business immediately, and anyone who can’t keep up usually loses.

In tennis you can lose against the opponent or against yourself. In a match there can be phases when you sense that the opponent is getting on the wrong track and having trouble with her own game, for instance, if she starts to hit too hard and makes unforced errors. In moments like these, it can be wise to ride the wave of the match dynamics, for example, to consciously become the passenger with little active intervention.

In doing so, one can, for instance, take a small step back from their own offensive style of play and deliberately return more balls with less speed to entice the opponent to play even more balls with too much power. However, it is...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.6.2024 |

|---|---|

| Vorwort | Dominik Klein |

| Verlagsort | Aachen |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport ► Ballsport |

| Schlagworte | Match • Match Point • mental game • Mental Training • professional tennis • Tennis • Tennis Player • tennis practice • tennis training |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78255-553-6 / 1782555536 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78255-553-7 / 9781782555537 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 8,3 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich