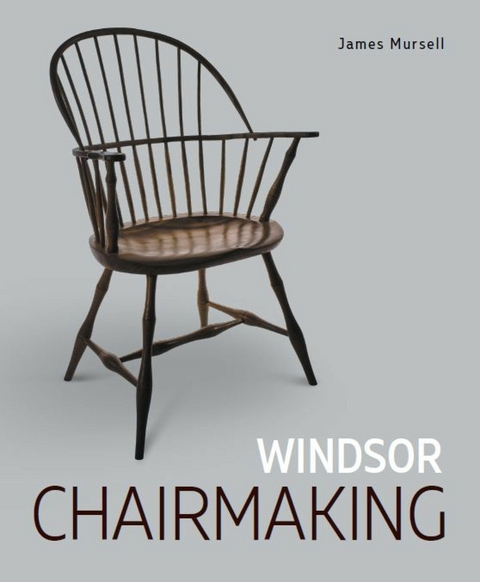

Windsor Chairmaking (eBook)

192 Seiten

The Crowood Press (Verlag)

978-0-7198-4362-4 (ISBN)

James Mursell has been making Windsor chairs since the mid-1990s. Initially he learnt from chairmakers in England and America but to a large extent is self-apprenticed, learning from constant experimentation and trial and error. He now teaches his craft from his home where he has built a teaching workshop on his farm. He promotes Windsor chairmaking by exhibiting and demonstrating widely around England and regularly writes for British woodworking magazines. Resident - West Sussex

INTRODUCTION

The golden period for Windsor chairs was between 1720 and 1800, just eighty years, or one lifetime. It is tempting for contemporary Windsor enthusiasts to wish to have been born during this exciting period, but we are probably much luckier to be alive today. We are able to see examples of the whole spectrum of chairs that were produced in this period from the distance of over two centuries, in spite of the loss and destruction of the vast majority of old chairs.

Most makers in the mid-eighteenth century would have been exposed to only a limited range of furniture, and most of that would have been made locally and exhibited only minor variation. Development was mainly incremental, but every now and again a step change would have been made by enterprising and imaginative makers who had been exposed to a much greater variety of influences, perhaps in London.

We must thank those early innovators who took the simple concept of a Windsor chair and developed it into a worldwide phenomenon, starting with individual makers and leading into the industrial production in the nineteenth century that epitomized the Victorian Industrial Revolution.

English double-bow in yew fruitwood and elm.

(Courtesy Michael Harding-Hill)

Today, with relatively inexpensive travel and the internet, we can study furniture from all over the world, and in particular Windsors from England and America. We are also fortunate that dedicated scholars have researched so thoroughly the developments of Windsor chairmaking on both sides of the Atlantic, in particular Nancy Goyne Evans who has produced the seminal works on the origins of Windsors and the development of American Windsor chairs, and Dr Bernard ‘Bill’ Cotton who has studied nineteenth-century English chairs so thoroughly.

Although interest in Windsor chairs almost died out in England and America at the beginning of the twentieth century, there has been a major revival in the past thirty years. Michael Harding-Hill and Charles Santore have championed the merits of eighteenth-century Windsors in England and America respectively, while Mike Dunbar and Jack Hill have introduced thousands of people to the delights of the chairs through their teaching.

A modern industrially made double-bow chair by Ercol.

(Courtesy Ercol)

Windsor chairs are still made today using industrial techniques. The best known manufacturer in Britain is probably Ercol, and many people who bought chairs from that company in the sixties are still proud owners, and keenly aware of the link to the past that these chairs represent. Windsors seem to be firmly embedded, even today, as a significant element in the histories of both England and America. Sadly many modern Windsors are not of such high quality as Ercol chairs. English pubs are full of modern manufactured Windsors, which aesthetically are quite depressing to anyone with an appreciation for the originals; and in America also, industrially produced Windsors can be seen everywhere. Unexciting as their designs may be, at least Windsors are still being made and used in good numbers.

This book will concentrate on chairs from that ‘golden’ period prior to 1800, and will pay little attention to chairs and designs made after that time. This reflects the author’s interests and inclinations, and should not discourage further study of these later chairs.

Checking the cut end of a felled oak tree for shakes – no problems were found.

Windsor chairs, even though they may have started life in the cities of London and Philadelphia, are nowadays considered ‘country’ furniture, and occupy a place in the woodworking pantheon with ladderback chairs. Both can be made with just the simplest of hand tools, and do not require the mastery of specialist techniques such as the cutting of dovetail joints before the first Windsor or ladderback is made. Thus the world of country chairs is far more accessible to woodworkers and prospective woodworkers than most forms of furniture. This is somewhat paradoxical as cabinet makers often consider chairs to be amongst the most difficult items to make. This relatively simple form of construction allowed artisans from other fields, such as wheelwrights, to make Windsors as part of their output as far back as the 1750s, and it is a good reason, for anybody who is interested, to make a chair today. It is hoped that this book will encourage the process.

Gimson ladderback chair with rush seat 1892 – 1904.

(© Victoria and Albert Museum, London)

The fact that green wood can be used for the chair’s construction is another feature that makes them attractive to people in the modern world. John Alexander in America and Mike Abbott in the UK have done more than most to publicize and promote green woodworking. Their enthusiasm for this type of material coincided with our increasing awareness of the environment and the importance of a sustainable lifestyle, both globally and individually. The use of the same word ‘green’ to describe both fresh, wet wood and also ‘consideration for the environment’ only enhances the interest that exists today for Windsor chairs, whether making new chairs or collecting/studying old chairs.

It is probably worth another word about ladderback chairs. Although they have a longer history than Windsors, they have never achieved quite the same prominence. Probably the best known examples were made by the highly commercial Shakers in America, who in the nineteenth century developed and promoted their chairs to make money for their communities. In England more recently the chairs of Gimpson and others have had a great following. Nobody can deny these chairs’ undoubted elegance, but it is perhaps possible to question their comfort in some cases. The reason for this is that ladder-backs tend to make fewer concessions to the human frame than Windsors – backs tend to be more vertical, and seats are not moulded to fit the posterior of sitters. However, some current makers, such as Brian Boggs, have combined form and function so successfully that comfort ceases to be an issue.

Ladderback chair by Brian Boggs.

(Courtesy Brian Boggs)

It may already be obvious that ‘country’ chairmakers tend to fall into either the ‘ladderback’ or ‘Windsor’ camp, but not both. It is a little like the love of cats and dogs, where most people love one or the other, but seldom both, though there are exceptions. Dave Sawyer, who makes the finest Windsors that I am aware of, in the woods of northern Vermont, began by making ladderbacks, but progressed to Windsors. He describes the Windsor as the Stradivarius of chairs, and I agree wholeheartedly with this sentiment!

Balloon-back Windsor chair by Dave Sawyer.

(Courtesy Dave Sawyer)

There is little doubt that Windsor chairs can become an addiction. You need only look at the number of people who have devoted significant parts of their lives to their study and making. No doubt each person is attracted to different aspects of these chairs, but I will try to explain what caused the addiction in me.

When I was very young my parents had Windsor chairs around our dining-room table, but soon acquired a set of Chippendale-style chairs from my grandmother. These were elegant chairs, but had embroidered seats stuffed with horse hair, which was none too comfortable on the legs to a young lad in short trousers. One up to Windsors!

At this same young age my father taught me to appreciate the pleasures of making things of wood, and this, combined with the love of these simple chairs, lodged in the back of my mind and lay dormant for almost thirty years. In the meantime I followed an academic rather than a practical education, culminating in a degree in botany. An MBA led to a number of years working in industry, both in England and America, and although I didn’t appreciate it at the time, this period of living in America would be a major influence in my chairmaking career.

In the mid-eighties I took over part of the family fruit-growing business, and after several years began, in the winter evenings, to make simple furniture based on lessons learned from my father and at school. Nearly thirty years had passed since I had sat on those Windsor chairs of my youth, but taking a chairmaking course to develop hand skills rekindled this interest and ignited a passion that has never left.

It was the simplicity of construction, and the ease with which one could create a thing of beauty and utility, that grabbed my attention. This combination perfectly matched the way that I work and think, and has informed my chairmaking ever since.

To bring my story up to date, chairmaking began to dominate my leisure time. I began to make chairs as a hobby, and within two years had taken a second course, this time in America. This introduced me to green woodworking, and finally gave me the means to begin creating the chairs that I could picture in my head. Sadly, fruit growing was becoming unviable and I closed down my farm in 2001. The upside of this difficult decision, and one that I have never regretted, is that it allowed me to devote all my time to Windsor chairs.

Ten days of formal instruction and fifteen years of selfapprenticeship have brought me to where I am now – and I’m still learning!

Windsor chairs are far more sculptural and organic in form than most cabinet work, and this is due to the lack of flat surfaces, parallel lines or...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 27.3.2023 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | 270 colour illustrations |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Freizeit / Hobby |

| Technik | |

| Weitere Fachgebiete ► Handwerk | |

| Schlagworte | anthropomorphic • Bow • pole lathe • round-tenoned • spindles • Splats • steam bent • stretchers |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7198-4362-6 / 0719843626 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7198-4362-4 / 9780719843624 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 37,8 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich