Strong Legs and a Full Quiver (eBook)

210 Seiten

Bookbaby (Verlag)

979-8-3509-4196-8 (ISBN)

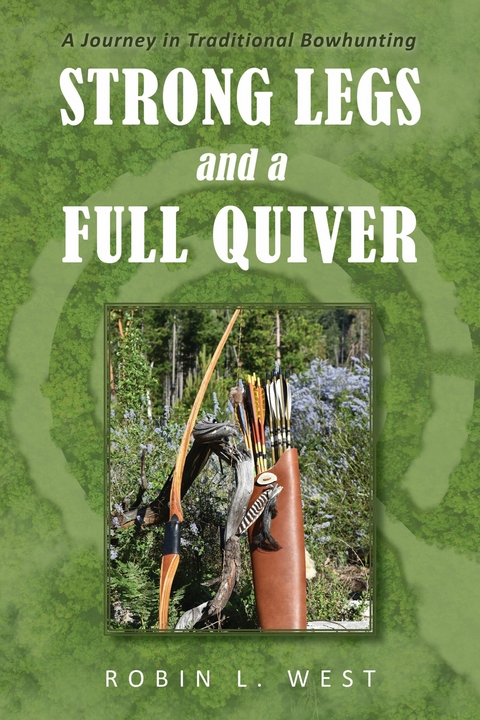

STRONG LEGS AND A FULL QUIVER is a compilation of stories about the author's life and how wildlife, wild places, and hunting helped define who he was, who he wanted to be, and where he would find challenges, lessons, and rewards in life. His passion for archery, and the use of traditional bows and arrows for hunting, was central to his journey. He grew up in a hunting family, and venison was a primary food. Hunting to fill the freezer was never a question posed in his home; how it was done was. The author grew in his awe of the history, simplicity, and lethality of recurve and longbows and learned to shoot them accurately and use them effectively to take a wide variety of game. He focused on the total experience: learning an animal's habits, gaining skills to stalk closely, using restraint before releasing an arrow at an animal, and utilizing it fully once harvested. The book acknowledges that the author found value in all of his hunts, whether successful or not, but that food was generally the underlying purpose of the activity. Because of this he often includes favorite recipes of harvested game at the end of a chapter. The stories include lessons, dangers, and sometimes humor in the author's real-life accounts of over 50 years of adventures from around the globe. The book includes 15 chapters, dozens of stories, and over 50 photographs.

Chapter Two

TRADITIONS AND CHOICES

Traditions are different for different cultures, individual people, and time periods. What is important as a tradition to one person may be nonsensical to another. So too, traditional archery can be defined differently by different people. For most, including references used by state fish and game agencies and regulators, “traditional archery equipment” is generally used to define recurve or longbows—pulled and held with the strength of one’s arms without aid of pulleys or cables. Individuals who participate in the sport may go further with their definitions to define traditional archery equipment to include only wooden arrows, fixed blade broadheads, and perhaps only to self-bows (made only with natural materials, without the aid of graphite or fiberglass). Some of this further refinement of the definition may come from personal beliefs, and that is fine, if it is focused on one’s self. It can become a distraction, if not a destructive force to the furtherance of the sport, if people allow their traditional beliefs to become too narrow and elitist. I started in the archery world using fiberglass-backed simple recurve bows and longbows, without sights or fancy arrow rests. I never used a release aid and preferred a tab over a glove to protect my fingers. I used wood, fiberglass, and aluminum arrows. I learned with this equipment and shot it endlessly. It was traditional for me.

Fairly soon after I took up the sport of archery, compound bows appeared on the scene. At the time, the choice was primarily between a simple fiberglass set-up marketed by Allen, or a range of strikingly beautiful wooden handled compounds made by Jennings. Within a couple of years, a few other designs hit the market, most notably from Bear Archery, and then the flood gates opened and compound bows (by the mid to late 1970s) were rapidly replacing stick bows. In all fairness, longbows had already largely been replaced by recurves. Until new designs from custom bowyers perfected limb modifications, such as the reflex-deflex design, hand shock from traditional English longbows made them uncomfortable to shoot, and many archers couldn’t master the weights needed to accurately propel a heavy hunting arrow with any degree of confidence. I would suggest that most archers at the time gave a compound a try, at least for a while. I was no exception. I got a Bear Polar II compound and used it for a couple of years. I killed a couple of bucks with it too and then gave it to a friend. It was heavy, got tangled in the brush easily, and the deer I killed with it weren’t any deader than the ones I had taken with my recurve.

Bear Archery had a marketing scheme in the seventies that proved effective. They sold a lot of archery equipment trying to reach rifle hunters—not necessarily to convert them to archery—but to become “two season hunters.” Many states at the time, including my home state of Oregon, had separate archery and rifle seasons for deer and elk, but a hunter wasn’t limited in their participation. They could hunt both seasons if they switched weapons. This allowed many people to be in the field for months rather than weeks, allowed using archery equipment early for deer, and the elk rut, and late for elk, and the deer rut, with a rifle in between if desired. What wasn’t to like? Two season opportunities, however, faded nearly as fast as they appeared. The longer seasons increased harvest, created crowding in popular areas, and created some worry about potential increased crippling loss from hunters who might be less inclined to learn to shoot their archery equipment well. Bowhunter education started up about the same time that fish and game agencies struggled with dialing back some of the opportunities that they had created. It wasn’t long before hunters had to choose their weapon type they would use for a species for the year, at least in many western states. Even that restriction wasn’t enough to reduce harvest and crowding over time and many of the historical general hunting seasons went to draw only. Some of this was deemed necessary because of more hunters in the field—the world’s population was growing but the world itself wasn’t getting any bigger. Some of it too was necessary because of increased success. Hunters armed with compound bows, sights, and release aids generally could learn to shoot reasonably well in less time and could shoot farther and more accurately than those that limited themselves to traditional equipment. Harvest success went up and opportunities had to be reduced.

As people were forced to make choices about how they preferred to hunt, public debate was common. Some rifle hunters wanted less archery opportunity arguing they were inefficient and resulted in unnecessary crippling loss. Counter arguments pointed out that archery equipment had proven effective at taking game for thousands of years and, that used properly, could be a very effective conservation tool. This was argued to be true for specific management goals that benefitted from using short-ranged weapons to reduce game populations in urban areas, to a longer view argument, suggesting that archery seasons allowed more hunters to be in the field enjoying the sport longer and had a valuable place in helping in hunter recruitment and bringing more hunter-conservationists into the fold. These discussions took place at state fish and game regulation meetings, in campgrounds and taverns, and in individual homes, including my own. My Dad was not a fan of bowhunting. He referred to arrows as “wounding sticks” and thought their use should generally be discontinued—artifacts of history and of simpler times. I would argue that the greater the challenge, the greater the reward. He would counter that if I wanted to get really close, I still could, just use restraint with a rifle until I stalked within a few feet and then shoot the animal in the ear. Our discussions were amiable, but he was pretty unchanging, until he saw me kill three bucks in three years. He was at my side with two of the animals, and they both were dead within seconds of being struck by an arrow and were quick and easy to recover. The next season Dad practiced with a Browning recurve and some cedar arrows and went hunting with me. He never shot well and gave it up after the one season, arguing that I was an exception and that most people couldn’t shoot well enough to hunt ethically with a bow. It was some years later before I realized that Dad was cross-dominant, and likely why he found trying to shoot a traditional bow instinctively to be very frustrating. Even with his difficulty using a bow personally, and apparent general disapproval of archery seasons, Dad supported my interests. He would drive me to hunting areas, operate a boat so I could shoot carp and bull frogs, and help me when I wanted to make arrows or alternations to my tackle.

Traditional archery tackle was used for a variety of activities.

By the time I had left for college, I had hunted and taken game with shotgun, rifle, handgun, muzzleloader, and both compound and recurve bows. I had a fair degree of competence with all of the weapons, but I already knew my weapon of choice was a traditional bow. The simplicity of design, the growing confidence I had when carrying one, and for numerous reasons that are hard to explain, I was the happiest when carrying a stick bow and a quiver full of arrows. Sometimes I would choose to use a different weapon for a hunt, but in later years, when physical conditions occasionally limited my choice to something other than a traditional bow, I felt a little bit cheated.

Getting Close

Traditional archery equipment generally does not allow for the same accuracy at distance that using a compound bow with sights offers. Some well-known archers, such as Howard Hill, gained reputations as modern-day Robin Hoods and amazed people with almost mystical abilities using traditional archery equipment, both at targets near and far, but they were the exception rather than the rule. All in all, however, the limited range that the average archer has when choosing traditional equipment, over using more technology, doesn’t have to mean much if the archer practices diligently with their equipment, hones their hunting skills to get close to their prey, and uses patience and thoughtful restraint when shooting. Consider in comparison using different firearms during the rifle season. One hunter may choose to carry their grandfather’s iron-sighted carbine and be limited in accuracy of approximately fifty yards. Another hunter may buy the latest and greatest flat shooting rifle with bipod and range-finding scope. With practice, they may shoot accurately out to 500 yards or even further. Both are rifles but they do not have the same effective ranges. The same is true with archery equipment. The basic limitations inherent to any particular piece of equipment, individual capabilities, and the amount of practice, will dictate the effective range of an archer. I was lucky. While growing up, I lived in a place that allowed daily practice, and it was rare that I didn’t get some in. There were large open fields behind our house, and less than two miles away (an easy bike ride before I drove) was an abandoned archery range. The trails at the old range wound around the mountain to abandoned shooting stations with large cedar bales, some still upright, and others toppled over. It didn’t matter. I could roam for hours—shooting from various distances and positions at the abandoned bales. This...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 31.1.2024 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport |

| ISBN-13 | 979-8-3509-4196-8 / 9798350941968 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 13,9 MB

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich