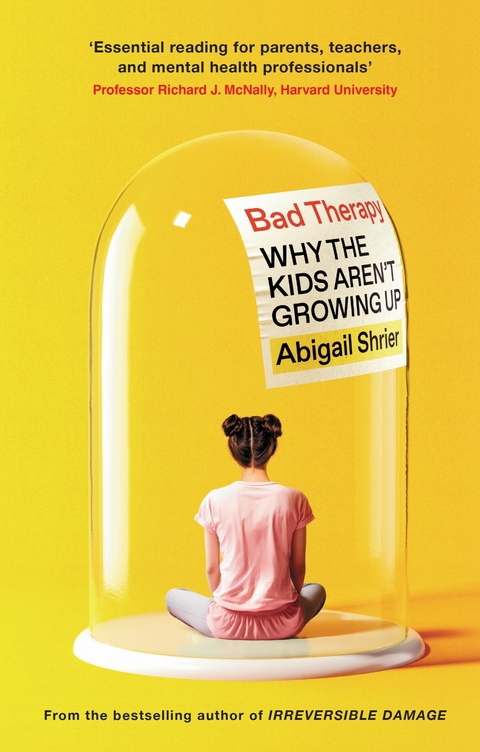

Bad Therapy (eBook)

288 Seiten

Swift Press (Verlag)

978-1-80075-414-0 (ISBN)

'A pacy, no-holds barred attack on mental health professionals and parenting experts ...thought-provoking' Financial Times

'A message that parents, teachers, mental health professionals and policymakers need to hear' New Statesman

In virtually every way that can be measured, Gen Z's mental health is worse than that of previous generations. Youth suicide rates are climbing, antidepressant prescriptions for children are common, and the proliferation of mental health diagnoses has not helped the staggering number of kids who are lonely, lost, sad and fearful of growing up. What's gone wrong?

In Bad Therapy, bestselling investigative journalist Abigail Shrier argues that the problem isn't the kids – it's the mental health experts. Drawing on hundreds of interviews with child psychologists, parents, teachers and young people themselves, Shrier explores the ways the mental health industry has transformed the way we teach, treat, discipline and even talk to our kids. She reveals that most of the therapeutic approaches have serious side effects and few proven benefits: for instance, talk therapy can induce rumination, trapping children in cycles of anxiety and depression; while 'gentle parenting' can encourage emotional turbulence – even violence – in children as they lash out, desperate for an adult to be in charge.

Mental health care can be lifesaving when properly applied to children with severe needs, but for the typical child, the cure can be worse than the disease. Bad Therapy is a must-read for anyone questioning why our efforts to support our kids have backfired – and what it will take for parents to lead a turnaround.

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 27.2.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie ► Krankheiten / Heilverfahren |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie ► Schwangerschaft / Geburt | |

| Medizin / Pharmazie ► Gesundheitswesen | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| Wirtschaft | |

| Schlagworte | ADHD • adolescence • antidepressants • Counselling • counsellor • gen z • Irreversible Damage • Mental Health • mental health industry • therapising • therapy • YOUTH SUICIDE |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80075-414-0 / 1800754140 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80075-414-0 / 9781800754140 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 1,4 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich