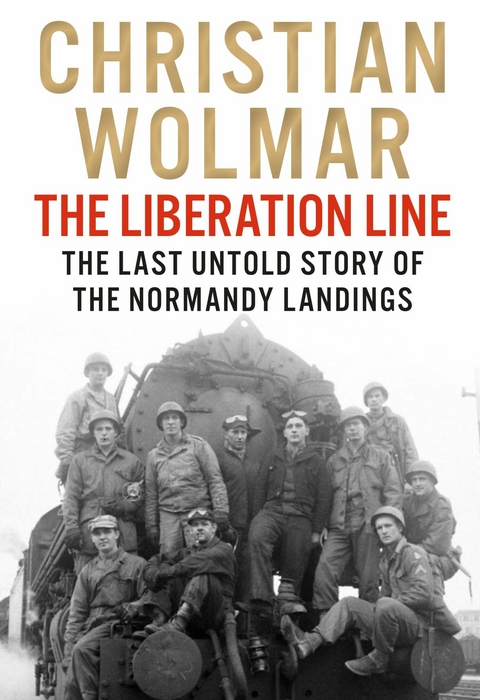

The Liberation Line (eBook)

384 Seiten

Atlantic Books (Verlag)

978-1-83895-753-7 (ISBN)

Christian Wolmar is a writer and broadcaster. He is the author of The Subterranean Railway (Atlantic Books). He writes regularly for the Independent and Evening Standard, and frequently appears on TV and radio on current affairs and news programmes. Fire and Steam: A New History of the Railways in Britain was published by Atlantic Books in 2007.

Christian Wolmar has written for every national newspaper and appears frequently on TV and radio as a commentator on transport issues. His previous books include the widely acclaimed The Subterranean Railway; Fire and Steam; Blood, Iron and Gold; Engines of War; The Great Railway Revolution; To the Edge of the World; Railways and the Raj; Cathedrals of Steam; and British Rail.

INTRODUCTION

GEORGE PATTON WAS not a happy man. His US Third Army, newly arrived in France a few weeks after the initial D-Day landings, was in danger of becoming bogged down. Patton’s reputation had been built on his ability to move and manoeuvre quickly. Static armies, he reckoned, were useless. His Third Army had just fought its way to Le Mans, a mere 150 miles away from Paris, surprisingly fast and he was anxious to keep up the momentum. Capturing the French capital was his goal and he reckoned that with the right support, he could reach the city within a couple of weeks. The fact that his superiors in High Command were concerned he was going too fast and would overstretch his supply line did not worry him. All he needed was enough gasoline to feed his precious tanks and trucks.

Patton had just achieved the near-miraculous feat of leading his Third Army out of the Cherbourg peninsula on a narrow road under constant threat of air attack. He had been so anxious to get his troops moving that he had spent a couple of hours personally acting as a traffic policeman, directing the flow of military vehicles at a vital crossroads. Nothing was going to stop him heading towards Paris except a shortage of fuel, and that was only because the damned planners had failed to recognize how fast armies could move.

It had been precisely Patton’s military nous that had persuaded General Eisenhower, the supreme commander of the Allied forces, to put the impetuous and impatient general in charge of the Third Army. Patton had become the go-to man when the military High Command wanted a rapid advance, earning that reputation in two earlier major campaigns in the war. In Tunisia in early 1943, he had taken over the leadership of a demoralized invasion force and instilled a fighting spirit by boosting morale and paying attention to detail. The result, barely a month after he took over, was the important victory in the Al-Guettar battle, the first in North Africa in which the Americans had overcome the German tanks. In Sicily, in the summer of that year, he had led another invasion force with great success, making effective use of the new amphibious trucks that were to play a vital part in Normandy. In both cases, Patton had taken over armies that consisted largely of inexperienced and untried troops and turned them into effective fighting forces through inspiring leadership and improved morale.

Patton was a formidable leader who was proud to call himself a cavalryman in an age when horses were no longer at the spearhead of any attacking army. He deliberately cultivated a flashy, distinctive image to win over the men under him. He carried an ivory-handled Smith & Wesson Magnum and on visits to the troops he invariably donned a perfectly polished helmet to go along with his riding pants and high cavalry boots. His jeep bore oversized placards displaying his rank on the front and back, as well as a klaxon horn that would loudly announce his approach from afar, notably when on visits to address his troops. His speeches, delivered without notes because of his dyslexia, were ‘simplistic, profane, [and] deeply offensive to some’,1 but proved effective at motivating the troops even if some of his officers disapproved of his use of bad language.

His enthusiasm, though, could quickly transform into intolerance. After a shameful episode in Sicily during which Patton slapped a soldier in a field hospital who, today, would be recognized as suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, it took Eisenhower’s intervention to prevent his dismissal from the army – though at the cost of being sidelined for a few months.

Eisenhower’s faith in Patton never wavered. And so it was Eisenhower himself who, in January 1944, appointed Patton to lead the American Third Army. This force was not to be part of the initial Normandy invasion which began on 6 June 1944 but rather to form a heavily armoured mobile group that would take advantage of an embattled enemy and sweep through France to the German frontier and beyond. Those two previous campaigns, however, had been short, both around a month long. Retaking continental Europe was bound to require a much longer effort. Even so, Patton wanted to make sure it took as little time as possible.

He had not wasted those months of preparation in England. The long delay before his army was sent abroad gave Patton the chance to turn his troops, many of whom had only arrived in Britain a month or two before crossing the Channel, into what he called a ‘hell on wheels’ outfit, as battle-ready as possible thanks to a gruelling training programme. And he did his homework. He read Edward A. Freeman’s book, The Norman Conquest, very carefully, focusing particularly on the sections describing the routes William and his army had used almost 900 years previously through Brittany and Normandy to reach the Channel.

Patton was also playing another role during his stay in England, one that involved no work on his part but was of vital importance to the preparations for the landing. He was a decoy, set up to fool German intelligence. He was the supposed commander of a phantom army group that appeared to be building up forces around Dover in order to attack Calais and Boulogne in the Pas-de-Calais, the nearest part of France to the English coast. This was part of a gigantic deception operation for the benefit of the German High Command, persuading them that they needed to reinforce that stretch of the coastline rather than Normandy where all the Allied forces ultimately were sent. Patton, as a successful general with a proven record of success, would have been perceived by the Germans as having a key role in any invasion force, which made him the perfect choice to lead this non-existent army. The confidence trick worked, with the Germans massing forces around Calais in anticipation of an attack that never came.

Patton was a general who both loved and hated war, but, irrespective of the horrors he had seen all too often, he always wanted to be in the thick of the action, and it was with relief that, at last, he crossed over to France on 4 July. His men, who would constitute the Third Army, were beginning to arrive there, too, but would kick their heels in camps behind the lines until the new army was officially brought into being. There was a delay because of bad weather and the slower than expected progress in the face of German resistance. Consequently, the Third Army was not activated until 1 August and even then not publicly acknowledged until two weeks later in order to maintain the subterfuge that there would be an attack via Calais.

The Third Army was to be the Allies’ secret weapon, the equivalent of the Germans’ Blitzkrieg, a force that would sweep through France in the same way the Germans had four years previously. From the outset, Patton deployed his troops with characteristic alacrity after the First Army’s initial breakout of the Normandy bocage – the difficult territory of hedgerows and ditches in northern France that made it hard for tanks to move forward and consequently the Allied invasion force had been stuck for weeks. After pushing through a bottleneck at Avranches, the crucial junction at the base of the Cotentin peninsula, the Third Army split into two, advancing simultaneously southeast towards Paris and southwest towards Brittany. The latter had initially been a priority but was now seen as a secondary objective. The main thrust was to be towards Paris and his troops progressed remarkably quickly, reaching Le Mans, 110 miles by road from Avranches, on 8 August.

Early on, the transport planners had expressed their doubts about the feasibility of Patton’s endeavour, suggesting that moving so fast was impossible, but their fears had been largely ignored. Consequently, Patton now faced an obstacle which risked stopping the Third Army in its tracks: it had overrun its supply line. Patton was not a man who would allow such base considerations as a lack of transportation to stop him – the planners be damned. He needed to establish a line of communication to support his troops, notably to provide enough gasoline to enable him to keep moving towards the French capital. Patton knew there was only one way that sufficient supplies could be brought forward. Road transport was proving too slow. The key roads were in terrible condition and were heavily congested with military and civilian traffic. Moreover, there was a shortage of trucks and drivers. There was nowhere for planes to land and, in any case, they could not carry adequate quantities of fuel. Only trains could provide sufficient supplies in good time. Patton’s demand was quite specific. He needed thirty-one train loads of gasoline to be delivered to the yard at Le Mans. And quickly.

His problem was that the railways had been wrecked – by the Allies themselves. Earlier in the year, the Allies had successfully launched their so-called Transportation Plan, relentlessly bombing the French network to prevent it being used by the Germans to bring up reinforcements to repel the Allied forces arriving on the beaches. While the authors of Operation Overlord, the Normandy invasion plan, had always envisaged a key logistical role for railways, they had assumed that the scale of the damage they had wreaked on the system would mean the railways would not be usable until much later in the advance towards Germany.

That, however, had been a grave mistake. As it turned out, the railways were needed far more urgently than anticipated and therefore considerable forces would need to be allocated to repairing them.

Patton was furious that the planners had not addressed this...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 2.5.2024 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | 2x8pp b/w plates and maps |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Natur / Technik ► Fahrzeuge / Flugzeuge / Schiffe ► Allgemeines / Lexika |

| Natur / Technik ► Fahrzeuge / Flugzeuge / Schiffe ► Militärfahrzeuge / -flugzeuge / -schiffe | |

| Natur / Technik ► Fahrzeuge / Flugzeuge / Schiffe ► Schienenfahrzeuge | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Neuzeit (bis 1918) | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► 1918 bis 1945 | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Militärgeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | Blood • British Rail • Churchill • D-Day • Dunkirk • France • Fury • Iron and Gold • liberation • Nazi Germany • Normandy • oppenheimer • Railways • Royal Engineers • Sabotage • Supplies • the monuments men • Trains • Vichy • World War II • World War Two |

| ISBN-10 | 1-83895-753-7 / 1838957537 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-83895-753-7 / 9781838957537 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 9,7 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich