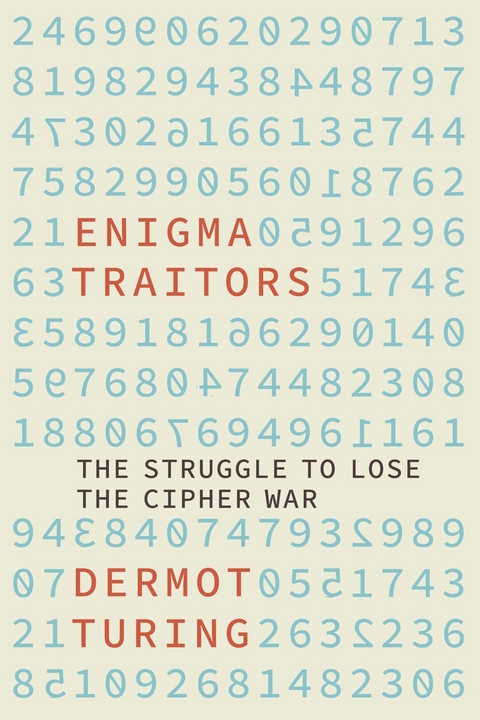

Enigma Traitors (eBook)

320 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-1-80399-180-1 (ISBN)

Dermot Turing is the acclaimed author of Prof, a biography of his famous uncle, The Story of Computing, and most recently X, Y and Z - the real story of how Enigma was broken. He began writing in 2014 after a career in law and is a regular speaker at historical and other events. As well as writing and speaking, he is a trustee of The Turing Trust and a Visiting Fellow at Kellogg College, Oxford. Dermot is married with two sons and lives in Kippen in Stirlingshire.

2FENNER |

Although a subject of his Imperial German Majesty, Wilhelm F. Flicke was born in Odessa in 1897. In 1915, he was expelled from Russia and impressed into the German Army, in which he found a role in radio interception.

The Armistice in November 1918 stabilised the situation in the West, but not the eastern marches of Germany. A newly emergent Poland found itself at war with both Germany and Russia in quick succession, and Flicke was observing the Poles and their radio behaviour. It was an embarrassing rerun of the opening days of the war, when the Russians lost the Battle of Tannenberg because of woeful radio and cipher security. Flicke observed sarcastically that, in 1919, ‘The Poles had to pay the same tuition fees that the Russians had had to pay at the beginning of World War I’.1

Despite the cost of bad security, seemingly everyone wanted to write about their educations. An American manual on codebreaking had appeared in 1916. There was a French textbook published in 1925, and an Austrian one in 1926.2 These two gave tantalising glimpses of the future, with mentions of automated cipher machines. The Austrian author even described Enigma – Chima AG’s publicity had made some impression. But if these seemed to be giving away tuition for free, the lessons that were hardest to understand came from Britain.

The price of private education in England could be astronomical, especially at the more exclusive schools. Possibly the most exclusive – indeed so exclusive as to be unheard of – was the Government Code & Cypher School. This institution was supposed to be unknown, yet its teaching materials were being distributed philanthropically to all, by none other than the British Government.

Winston Churchill’s book on the war, The World Crisis, was published in German by R.F. Koehler of Leipzig in 1924. On page 367 of Volume I, Churchill dropped a bit of a clanger: ‘The sources of information upon which we relied were evidently trustworthy […]’ He might not have said it explicitly – the Cabinet Secretary vetoed explicit mention of codebreaking – but to the other side, what Churchill was referring to was plain enough. Writing about this in 1934, a German naval staff officer noted that the Kaiser’s naval failures were linked to radio communications.3 The German Navy had paid its tuition fees.

It wasn’t just Churchill. The most senior and most wily officer in the Room 40 codebreaking operation at the British Admiralty during the war was Admiral ‘Blinker’ Hall – he, too, was distributing free crib sheets to the Germans, specifically 269 decrypted German messages made available to a German–American claims commission in 1926.4 To cap it all, there was Sir Alfred Ewing, notionally Blinker Hall’s boss, who spoke about the secret activities of the GC&CS’s predecessor in December 1927. His remarks, remarkably, were reported in The Times:

WAR WORK AT THE ADMIRALTY

SECRETS OF ‘ROOM 40.’

HOW GERMAN MESSAGES WERE DECODED

Sir Alfred Ewing, Principal of Edinburgh University, addressed the Edinburgh Philosophical Institution in the United Free Church Assembly Hall, Edinburgh, last night on his experiences at the Admiralty during the War […] The deciphering office was soon established as a separate branch of the Admiralty under the lecturer’s direction […] When the work had passed its initial stage, as many as 2,000 intercepted messages were often received and dealt with in the course of 24 hours. In this way a close and constant watch was kept on the German Fleet.5

Maybe Sir Alfred imagined that foreigners didn’t read The Times, but a translation was circulated in the Imperial German Admiralty within days.6 Indeed, the Ewing speech was a horrible reminder of the embarrassment of the Zimmermann Telegram. Six column inches later, Sir Alfred went on:

Besides intercepting naval signals, the cryptographers of Room 40 dealt successfully with much political cipher […] Among the many political messages read by his staff was the notorious Zimmermann telegram […], which revealed a conditional offer to Mexico of an alliance against the United States […] Its publication was decisive in converting American opinion to the necessity of war.

While the defeated Germans were trying to improve their own cipher security, the British were bragging about their codebreaking skills. Maybe the British needed some schooling of their own: if their aim was an uplift in German security, this was a rather good start.

For once, Chima AG was in luck: the Imperial Navy had set its own course for cipher security. Ships at sea cannot use landlines, and the war had taught the Naval Staff how dependent it was on radio telegraphy. Back in 1918, it was the navy that Arthur Scherbius first approached with his idea for a cipher machine, but the collapse of Germany and the debacle of Versailles put paid to that.7 However, on 26 August 1925, Commander Guse, the officer commanding the naval B Service (‘B’ standing for Beobachtung, or surveillance, a coy cover for the interception and decryption of foreign naval signals) placed an order with Chima AG for fifty Enigma machines.8

Commander Guse had very specific requirements for his machines – these were not going to be the unreliable typewriting versions, but the compact models in boxes, where the output was given by illuminating lettered torch bulbs. He also wanted a twenty-nine-letter keyboard, five interchangeable rotors to provide more variety in the cipher creation process, silent operation, and more – in total, twenty-four – specifications.

In a memoir written in 1950, a senior member of Guse’s team summed up the situation:

In the mid-twenties, the first mechanical cipher machine ‘Enigma’, or Radio Cipher M as it was officially called, was introduced into the German Navy. Analytical studies showed that the machine was only partially secure. The design still had significant defects. The design was significantly improved with changes proposed by the B Service control centre […] It had always been the policy of the B Service control center to gain the highest level of experience through close cooperation with the Decipherment Centre of the Armed Forces (OKW Chi). The exchange of experiences was very fruitful and benefited both sides.9

The rescue of Chima AG was a combined operation, relying on co-ordinated action between the two main branches of the armed forces. The OKW Chi (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht Chiffrierstelle) began, under the leadership of one Captain Rudolf Schmidt, conducting its own trials of Enigma in 1926.10

Captain Schmidt was a rising star. Born in 1886, he began a military career in conventional style as ensign in an infantry regiment at the age of 20. He was doing well enough on the army career ladder to be nominated for a place at the Military Academy, with matriculation due in October 1914. World events disrupted that plan but provided him with valuable experience on both Eastern and Western fronts. By 1915, Schmidt was a captain in charge of signals and telegraphy, and afterwards assigned to the General Staff.

At the war’s end, he was one of the few junior officers kept on in the tiny rump army allowed under Versailles. Then, in April 1925, he became head of the OKW Chi. The question of how Germany’s secrets could be kept secret was back on the table, and Captain Schmidt had been supplied with an example of the typewriting Enigma as a possible way of dealing with the problem.

In addition to cipher security, Schmidt wanted to build up the other side of operations at the OKW Chi:

With the takeover of the management of the Chi by Captain Schmidt, a new phase began in the development of the Chi. Schmidt’s comprehensive general education, his nuanced assessment of political power games, his knowledge of the disastrous effects of a bad – and the benefits of a good – German Intelligence Service gave Chi the opportunity to expand the field of work of the codebreaking function well before political crises and new power cultures made the breaking of other countries’ codes necessary […] Under his leadership, secret signals of the Russian, Polish, Czech, Italian and French army and air forces, and Polish, Romanian, Serbian, Italian, French, Dutch, Belgian, English and American (USA) diplomatic signals, were decrypted in real time, even though they used a complex tangle of superencipherment.11

The head codebreaker was Wilhelm Fenner, who joined the OKW Chi in the autumn of 1921. Fenner was born and grew up in St Petersburg. He went on to study sciences in Berlin and an engineering career beckoned. Then the war changed things: he saw service on the Russian, Italian, Western and Balkan fronts and then was employed in the army as a Russian interpreter. For a year or so after the war, he wandered through various unsatisfactory journalistic jobs, eventually finding himself in Paris where white Russian émigrés were congregating.

Fenner became acquainted with one of them, a one-time astronomer to the Tsar, now a ‘Professor of Applied Tactics’, called Pyotr Novopashenniy. Novopashenniy wanted to settle down in Berlin and he thought he could be of assistance to the German General Staff for, during the war, he had been director of the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 2.11.2023 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► 1918 bis 1945 | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Militärgeschichte | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung ► Staat / Verwaltung | |

| Schlagworte | Alan Turing • allied espionage • Bletchley Park • code-breakers • Code breaking • Enigma • german code breakers • german enigma cipher • german espionage • second world wars • Spies • World War Two • WWII |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80399-180-1 / 1803991801 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80399-180-1 / 9781803991801 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 9,4 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich