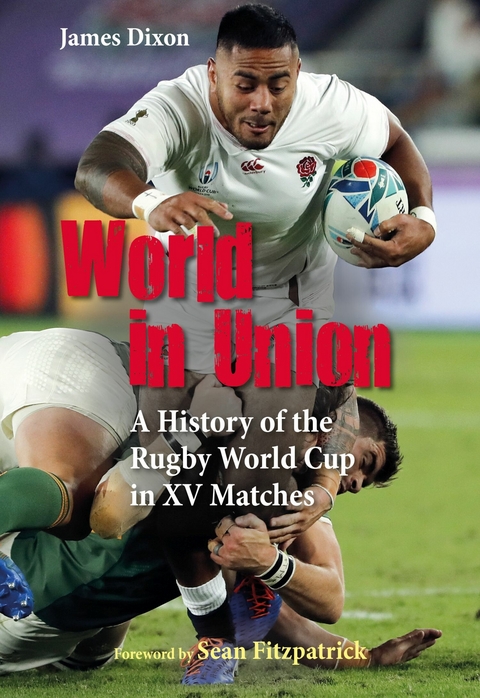

World in Union (eBook)

288 Seiten

Meyer & Meyer (Verlag)

978-1-78255-532-2 (ISBN)

James Dixon (Rugby World, FourFourTwo, Athletics Weekly) is a sportswriter and historian with an interest in the social, economic, and political history of sport. His debut book, The Fix, told the story of the establishment of the UEFA Champions League during a period of economic and political tumult in Europe and European football. In World in Union, he's turned his attention to the Rugby World Cup and the existential role it played in rugby's battle between amateurism and professionalism. James currently resides in England.

James Dixon (Rugby World, FourFourTwo, Athletics Weekly) is a sportswriter and historian with an interest in the social, economic, and political history of sport. His debut book, The Fix, told the story of the establishment of the UEFA Champions League during a period of economic and political tumult in Europe and European football. In World in Union, he's turned his attention to the Rugby World Cup and the existential role it played in rugby's battle between amateurism and professionalism. James currently resides in England.

The Pre-Match

Nick & Dick versus The International Rugby Board

March 21, 1985, Paris

‘If someone did not do something towards promoting the game,

it would eventually curl up and die’

Dick Littlejohn, New Zealand

Chaos theory hypotheses that small, seemingly inconsequential events can lead to major divergences in outcomes. A county cricketer suffering an injury while bowling against Nottinghamshire may have been the flapping butterfly wing that led to the inauguration of the Rugby World Cup.

Basil D’Oliveira was born in Cape Town, South Africa. He emigrated to England in 1960 because the Indian part of his mixed Indian and Portuguese ancestry was barring him from being selected as a Test cricketer for apartheidera South Africa.

After satisfying a three-year residency requirement, D’Oliveira began playing for Worcestershire and received an England call-up in 1966. D’Oliveira was in and out of the side during the 1968 Ashes. However, a superb 158 in the final Test of the summer at the Oval seemed to have secured his place on that winter’s tour to South Africa.

Under intense political pressure from the South African government, the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) (under whose auspices the England cricket team formally toured until 1977) declined to select D’Oliveira. The Warwickshire all-rounder Tom Cartwright, who hadn’t played Test cricket since 1965, was chosen instead. The omission prompted an outcry in England. Most believed D’Oliveira had earned his place on merit and was being denied it on the grounds of race.

When Cartwright, a working-class lad from Coventry with socialist sensibilities, withdrew from the touring party (officially due to an injury, but many suspected partly mixed with morality), the MCC belatedly selected D’Oliveira. B. J. Vorster, Prime Minister of South Africa, gave a sharply critical speech about D’Oliveira’s inclusion and the MCC opted to tour Pakistan instead.

The D’Oliveira affair was not the first sporting boycott of the apartheid state. Still, it was the first in one of the two main sports of the ruling Afrikaners and directly led to South Africa’s total exclusion from international cricket from 1970 onwards.

In 1956, the International Table Tennis Federation severed its ties with the all-white South African Table Tennis Union. FIFA suspended South Africa from international football in 1963, and the International Olympic Committee excluded South Africa from the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo.

As early as 1934, the British Empire Games, the precursor to today’s Commonwealth Games, had to be relocated from Johannesburg to London for fears over whether non-white athletes would be allowed to compete. However, rugby’s relationship with apartheid South Africa was more complicated.

Unlike cricket, rugby did not benefit from having teams like India, Pakistan and the West Indies at its top table. Until 1978, only seven countries (Australia, England, Ireland, New Zealand, Scotland, South Africa and Wales) were represented on the International Rugby Board (IRB). The IRB was an anglophone, almost exclusively white organisation, more concerned with preserving amateurism than dismantling apartheid.

In 1960, South Africa refused to grant New Zealand’s Māori players admission to enter the country. Shamefully, the All Black tour proceeded with an all-white team. The political fallout of that decision meant that New Zealand didn’t tour South Africa again until 1970 when Māori and players of Samoan heritage were allowed but designated by their hosts as ‘honorary whites’.

Stop the Tour – a protest group led by future Labour Cabinet Minister Peter Hain and including future UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown – disrupted the Springbok tour of the British Isles in the winter of 1969–70 with a civil disobedience campaign.

Halt All Racist Tours (HART), a similarly minded Kiwi organisation succeeded in having the Springboks’ 1973 invitation to tour New Zealand revoked by the country’s social democratic prime minister. Norman Kirk said a South African Rugby team touring New Zealand under the present circumstances would lead to the ‘greatest eruption of violence this country has ever known’.

However, Kirk’s untimely death in August 1974 at just 51 led to a change of government. The National Party’s Robert Muldoon won the 1975 New Zealand general election and refused to prohibit the proposed 1976 tour of South Africa by the All Blacks.

The Australian government refused permission for the plane carrying the All Blacks to South Africa to refuel on its territory. Consequently, New Zealand travelled to South Africa via the United States, Portugal and Nigeria.

New Zealand wasn’t alone. Much of the rugby world seemed determined to maintain sporting contact with South Africa. England toured South Africa in 1972 and France in both 1971 and 1975. The British & Irish Lions had toured South Africa in 1974, but some players like Wales’s John Taylor and Gerald Davies had refused on moral grounds.

Commonwealth heads of government, including Muldoon, signed up to the 1977 Gleneagles Agreement, which was supposed to curtail sporting contact between Commonwealth countries and South Africa. However, since cricket already had its own ban, the Gleneagles Agreement aimed chiefly at hurting Afrikaner pride where it mattered most to them – the rugby field.

Rugby, with the notable exception of Australia, ignored the Gleneagles Agreement. The Lions toured South Africa again in 1980, while the Springboks toured New Zealand in 1981.

Although the Foreign Office briefly discussed confiscating passports from prospective tourists, Margaret Thatcher’s government took the view that all they could do was dissuade, not prohibit. Replying to a letter from the President of Liberia, Thatcher wrote, ‘We have sought by all the means open to us to discourage the tour … the fact, however, remains that our governing bodies of sport are rightly autonomous and Ministers do not have the power to direct them.’

Muldoon came up with an even more mealy-mouthed formulation of words. He said his government did not want the tour to go ahead but would do nothing to stop it. The National Party had one eye on the 1981 New Zealand general election and courted the votes of rural New Zealanders more likely to support the Springbok tour.

Hundreds of HART protestors succeeded in getting the second tour match played in Hamilton abandoned. Days later, a protest in Wellington at the South African High Commission turned violent with police baton-charging protestors.

The New Zealand Commissioner of Police advised the government that the police could not guarantee security and recommended cancelling the tour. However, Muldoon ignored the Commissioner and deployed the New Zealand military to ensure the tour he was publicly against went ahead. Subsequently, Muldoon’s National Party won a third term with a one-seat parliamentary majority even though they gained fewer votes than the opposition Labour Party.

HART heavily protested all three Test matches, and All Blacks captain Graham Mourie made himself unavailable for selection, later saying, ‘You’ve got to be able to look at yourself in the mirror’.

Security was ramped up for the deciding Test match, turning Eden Park into a fortress. A fortress HART protestors were very willing to lay siege to. Most memorably, two protestors, Marx Jones and Grant Cole, hired a prop plane to rain flour bombs down on the players below. When All Black front-row forward Gary Knight was felled by a flour bomb, South African captain Wynand Claassen asked if New Zealand had an air force.

Playing South Africa at home was now practically impossible. Even if governments allowed tours to go ahead, their citizenry in tune with the horrors of apartheid would not.

Not being able to play the Springboks was a mild inconvenience to the Five Nations, who could bank on two sell-out crowds each season to swell the coffers of their respective unions, but a significant problem for Australia and New Zealand. Playing South Africa was partly how the southern hemisphere unions made their money. Lions tours were infrequent, and despite the Australasian teams touring Britain since the Edwardian era, England had only reciprocated with three visits Down Under.

The answer was clear: Rugby Union needed a World Cup.

After all, FIFA held their first World Cup in 1930, Rugby League managed to host one in 1954 and even cricket had modernised enough by 1975 to stage an eight-team tournament.

In 1982, the Australian Rugby Union sought the IRB’s permission to host a World Cup in 1988 to coincide with the bicentenary of Australia. Not to be outdone in 1983, the New Zealand Rugby Union (NZRU) proposed they host a World Cup in 1987. However, given the opposition among the home unions to the concept, the two Barbarians at the gate realised they couldn’t waste their energy fighting each other. A World Cup hosted jointly by Australia and New Zealand in 1987 was proposed.

The ‘Nick and Dick Show’ was born. Nicholas Shehadie of the Australian Rugby Union and Dick Littlejohn of the NZRU toured the world and made the case for a Rugby World Cup.

‘The game of rugby needed to be advanced worldwide … we were convinced of that,’ said Littlejohn. ‘If someone did not do something towards promoting the game, it would eventually curl up and die.’

The IRB split on the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.9.2023 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | Aachen |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport ► Ballsport |

| Schlagworte | All Blacks • Murderball • Rugby • rugby history • rugby world cup • Scrum • Sport History • Sport narrative |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78255-532-3 / 1782555323 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78255-532-2 / 9781782555322 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 3,2 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich