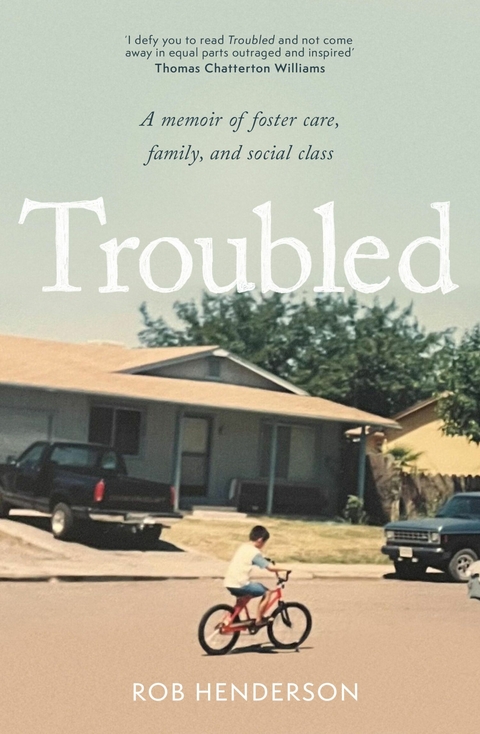

Troubled (eBook)

290 Seiten

Forum (Verlag)

978-1-80075-365-5 (ISBN)

Rob Henderson grew up in foster homes in Los Angeles and the rural town of Red Bluff, California. He joined the Air Force at the age of seventeen. After his enlistment, he graduated from Yale University with a BS in psychology and was subsequently awarded a Gates Cambridge Scholarship. Once described as 'self-made' by the New York Times, Rob received a PhD in psychology from St. Catharinexe2x80x99s College, Cambridge in 2022. His writing has appeared in the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the Boston Globe, and the New York Post, among other outlets. Robxe2x80x99s popular Substack newsletter is sent each week to more than forty thousand subscribers.

CHAPTER ONE

Until Your Heart Explodes

I graduated with a BS in psychology from Yale University on May 21, 2018. Shortly before the commencement ceremony, I walked through the idyllic campus one last time with my sister. A friend from class loudly called my name as we passed. He and his boyfriend joined us, saying they needed a short break from their families. My sister snapped photos of the Gothic architecture for her Instagram story.

My friend grinned and wrapped his arm across my shoulder, whispering “So who is she?” and tilting his head toward Hannah.

“Matthew,” I replied, “that’s my sister.”

“What? You guys don’t really look alike.”

“I’m adopted. I’ve told you this.” Matthew was right. Although my adoptive sister and I share a similar ethnic background—both of us are half Korean—there isn’t much of a resemblance.

“Oh, right. Wow. Yale and now Cambridge. And you’re like the only foster kid I know. Dude, your family won the adoption lottery!”

I laughed with him. “Yeah, maybe they did.”

If you ask most people to recall their earliest memory, it’s usually from when they were around age three. Here is mine.

It’s completely dark. I am gripping my mother’s lap. Burying my face so deeply into her stomach I can’t breathe. I come up for air and see two police officers looming over us. I know they want to take my mom away, but I’m scared and don’t want to let her go. I fasten myself to her as hard as I can.

My internal alarms are going off and I’m sobbing. I want the strange men in black clothes to leave.

The memory picks up, like a dream, in a long white hallway with my mother. I’m sitting on a bench next to her drinking chocolate milk. My three-year-old legs dangle above the floor. I sneeze and spill my chocolate milk. I look to my mom for help, but she can’t move her arms. She’s wearing handcuffs.

My mother came to the United States from Seoul, South Korea. Her father, my grandfather, was a former police detective who had grown wealthy after starting a fertilizer company. My mother moved to California as a young woman and completed one semester of college before dropping out. Her parents supported her while she studied. After I was removed from her care, she was asked by a forensic psychologist if she had taken drugs in college. She replied, “It was a psychedelic age.” Several years after arriving in the US, she met my father, and became pregnant with me. As an adult, I took a DNA test that revealed that my father was Hispanic, with ancestry from Mexico and Spain. He abandoned my mother shortly after her pregnancy, and I have no memories of him. According to the social worker responsible for my case, my mother had two sons with two other men before becoming pregnant with me. I’ve never met my half-brothers. I’ve never tried or wanted to. From a young age, I wanted to distance myself from any reminder of my origins.

When I was a baby, my mother and I lived in a car. About a year later, we moved into a slum apartment in Westlake, a poor neighborhood in Los Angeles. Documents from social workers report that my mother would tie me to a chair with a bathrobe belt so that she could get high in another room without being interrupted. She left bruises and marks on my face. While my mother did drugs, I would cry from the other room as I struggled to break free.

Eventually, after many instances of this, neighbors in the apartment complex overheard my screams. They called the police. Later, I obtained a report from a Los Angeles County forensic psychologist:

I have received reports from her apartment manager that she has been associating with known drug users. There have been many people, mostly men, in and out of her room at all hours, and allegations that she is exchanging sexual favors for drugs. She denies these accusations.

In view of the above, I cannot recommend she have custody of her son at this time. While I do not doubt her love for her son, the atmosphere in which she has chosen to live is not conducive to child-rearing. Furthermore, she may soon be homeless again.

After her arrest, my mother was deported to South Korea. I never saw her again. It’s funny, many nonadopted people have asked me if I’ve tried to find her, and when I say I haven’t, they often react with surprise. But other adopted people seldom ask me about whether I’ve tried to find my birth parents, and when they do, they’re never surprised when I say I haven’t. Why try to find someone who did not want you in their life?

No father, no mother. I was three years old when I entered the Los Angeles County foster care system.

One in five foster kids are placed in five or more homes throughout their time in the system. Three-quarters of foster kids spend at least two years in foster care. Thirty-three percent stay five or more years. One in four are adopted. The median age for leaving foster care is seven years old.1 I am a data point for each of these statistics. I am often asked why foster kids are moved into so many different homes, even when things are going relatively well. One reason is that, oftentimes, a birth parent or family member will later become available to care for the kid. But if the child has grown too attached to their foster parents, this can create problems. So, kids preemptively get shuffled around so that they don’t get too attached to any one particular home. But there are plenty of kids like me, with no possibility of being taken in by a family member, whom this strategy needlessly deprives of stability.

According to documents from my social workers, I lived in seven different foster homes in Los Angeles in total. In two of the placements, my stays were brief—less than a month—and nothing noteworthy occurred. In two others, I can’t report what happened because, to my dismay, I simply can’t remember. It’s possible that these experiences were so upsetting that the memories weren’t encoded. It’s also conceivable that I stayed in these homes for such a short amount of time that my recollections of them blended with the placements I do remember—this is what I hope occurred. I have substantive memories of three of my foster homes.

After I was taken from my mother, there was a blur of different adults buzzing around me. I felt confused and terrified. On the way to my first home, still distressed over my separation from my mother, I vibrated in my car seat as my social worker drove. Eventually I fell asleep from physical and emotional exhaustion and woke up in a foster home.

It was a small and crowded duplex. There were seven kids in my new home, mostly Black and Hispanic, plus one white kid. Race wasn’t a big deal in any of my homes, though. Size was more important. An older kid, around twelve years old, was the ringleader. He controlled the television channel with the threat of violence if any of us tried to watch what we wanted. We spent most of our time watching TV, roughhousing without much adult supervision, and scrounging around for food. MTV was usually on in the background, and it seemed like “Waterfalls” by TLC played every day.

After a few months of this, I got used to living there. One day, I was playing with the other kids under a table, pretending to be a dinosaur. Suddenly, an adult trespassed on our fantasy. This was rare. Typically, the adults in this home left us alone, except to feed and bathe us. I reluctantly peered out from under the table. A Black woman knelt down and said it was time for us to go. I recognized her as Gerri, the woman who first drove me here to my new home. Instinctively, I knew she was taking me somewhere else, and I would not return. Some part of me suspected that my arrangement was not meant to last. Even at four years old, I remember being confused that the people on-screen had different kinds of families than we did. The TV families were all the same. The kids always lived with the same parents; they never had to live with others. I’d also seen some of my foster siblings leave, and new ones had come to join us.

Gerri repeated that it was time to go. I started crying. The kind of crying where kids lose control of their bodies and forget how to breathe. I gripped one of the table legs, refusing to let go. My foster parents told me it was okay, that I would join a new foster family. Their words weren’t registering. I didn’t want a new family; I wanted to stay with what was familiar.

They were the only parents I had really known, even though I barely saw them. I had no idea where I was going next. I bawled the entire way to the new foster home. And when we arrived, I clutched Gerri, unwilling to let go of her leg. She was my new anchor. She was the only familiar thing in this strange new home, full of strange children and adults speaking a language I couldn’t understand. The house was located in West Covina, a working-class area of LA County composed mostly of Hispanic and Asian families.

I didn’t eat much for my first couple of days. Anytime my new foster parents, the Dela Peñas, tried to feed me, I’d push the food away, saying I had a stomachache. I did, from the distress of being taken from my previous foster placement. But I was also, without realizing it, on a hunger strike. I thought if I didn’t eat for long enough, maybe Gerri would reappear and I could ask her to take me back to my last home. She didn’t, and eventually my appetite returned.

My new foster parents were from the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 20.2.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie ► Esoterik / Spiritualität | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie ► Makrosoziologie | |

| Schlagworte | Coming-of-age • educated • Elite universities • foster care • Hillbilly Elegy • income inequality • JD Vance • luxury beliefs • Memoir • Military • privilege • Social Class • tara westover • US Air Force |

| ISBN-10 | 1-80075-365-9 / 1800753659 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-80075-365-5 / 9781800753655 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 987 KB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich