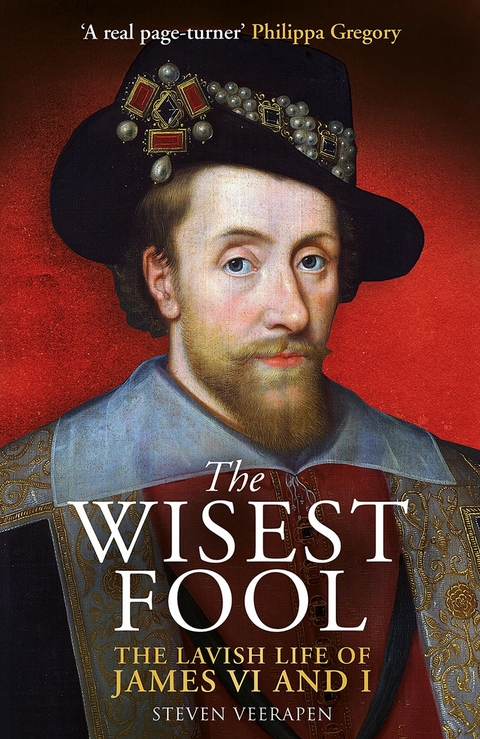

Wisest Fool (eBook)

432 Seiten

Birlinn (Verlag)

978-1-78885-640-9 (ISBN)

Steven Veerapen was born in Glasgow to a Scottish mother and a Mauritian father and raised in Paisley. Pursuing an interest in the sixteenth century, he was awarded a first-class Honours degree in English, focussing his dissertation on representations of Henry VIII's six wives.

James VI and I, the first monarch to reign over Scotland, England and Ireland, has long endured a mixed reputation. To many, he is simply the homosexual King, the inveterate witch-roaster, the smelly sovereign who never washed, the colourless man behind the authorised Bible bearing his name, or the drooling fool whose speech could barely be understood. For too long, he has paled in comparison to his more celebrated Tudor and Stuart forebears. But who was he really? To what extent have myth, anecdote, and rumour obscured him?In this new and ground-breaking biography, James's story is laid bare and a welter of scurrilous, outrageous assumptions penned by his political opponents put to rest. What emerges is a portrait of Elizabeth I's successor as his contemporaries knew him: a gregarious, idealistic man obsessed with the idea of family, whose personal and political goals could never match up to reality. With reference to letters, libels and state papers, it casts fresh light on the personal, domestic, international and sexual politics of this misunderstood sovereign. 'A real page-turner for lovers of history' - Philippa Gregory

Steven Veerapen was born in Glasgow to a Scottish mother and a Mauritian father. He graduated with 1st Class Honours from the University of Strathclyde and was awarded a PhD in 2014 He is currently teaching associate in English at Strathclyde. In addition to his academic work, he has also written a number of historical novels, and his crime mysteries featuring Anthony Blanke, set in Tudor England, is published by Polygon.

1

Baptism of Fire

If there is one thing all can agree on about Mary Queen of Scots, it was that the glamorous, French-educated sovereign knew how to put on a show. And that, during the chilly December of 1566, was exactly what she intended to do.

The occasion was the baptism of her son and heir, Charles James Stuart, whom she expected to succeed her as James VI of Scotland and, if she had her way, James I of England, assuming her own claim to the English Crown was duly recognised. As he was the putative heir to both British nations, it was important that the world should be aware of the baptism. Accordingly, the invitations had gone out the previous August: to England, France, Savoy; the black velvet gowns (black being a particularly expensive colour) had been ordered to outfit the prince’s nurses; a cradle had been especially carved and covered in a cloth-of-silver blanket; and, less charmingly, £12,000 Scots had been chiselled out of the Scottish people.1 As it had under earlier Renaissance monarchs, such as James IV and James V, a little bit of continental flair was coming to Scotland.

Stirling Castle, perched on its craggy rock overlooking the royal burgh of Stirling, was the venue. Accordingly, the night sky above the town came to life with the novel spectacle of fireworks. Below, the baby prince was carried to the courtyard’s chapel by the French ambassador, who walked through an avenue of Scottish barons and was followed by the country’s Catholic noblemen, bearing the accoutrements of baptism. Soldiers were clad in ‘Moorish’ costumes, the better to entertain the visiting dignitaries as they laid siege to a mock castle. A banquet – then a term denoting rich sweets and drinks – was given in the hammerbeam-roofed Great Hall, which rocked with music and pulsed with torchlight. Latin verses composed by the leading humanist George Buchanan were sung, followed by Italian songs and masques. The festivities carried on over three days, from the 17th to 19th, in a blaze of bonfires, fireworks, hunts, and cannon blasts. The ambassadors were suitably impressed and eager to play their part, distributing their gifts of a solid gold baptismal font (from England, but too small to baptise a six-month-old), jewelled fans, and earrings for the prince’s mother.

This frenzy of revelry was, however, an example of the beleaguered Queen of Scots protesting too much – an attempt to paint a little gold leaf over the deepening cracks within the political nation. Conspicuous by his non-appearance was the baby’s father, Henry, uncrowned King of Scots – more often known by his lesser title of Lord Darnley. Though provided with a suit of cloth-of-gold, the supposed king remained immured in his chambers at the castle, preferring not to face the contempt of foreign ambassadors, who were all too aware of the division between him and his wife and sovereign. Most irritating of all was that Elizabeth of England, sovereign of the country in which he had been born and raised, had expressly forbidden her ambassador, the 2nd Earl of Bedford, from acknowledging him at all.

This suited Queen Mary. Legends have abounded over the centuries about her whirlwind romance with Darnley, and they have rather tended to obscure what really went on in 1565. Then, the Englishman had been given leave by Elizabeth to leave his homeland to travel north, where Mary intended to rehabilitate his troublesome father, the exiled Matthew Stuart, 4th Earl of Lennox. This had suited both sovereigns, as well as the earl. Mary, having been widowed when her first husband, the French king, Francis II, died, was actively seeking a husband on the continent. Lennox had Scottish royal blood and his ambitious wife was descended, like his cousin the Scottish queen, from the elder sister of Henry VIII; thus, their son had a good claim to both the thrones of England and Scotland. This Queen Mary knew. Elizabeth knew it too, and it seems likely that she hoped to throw a spanner in Mary’s marital plans by letting the handsome Darnley intrude on her life. What the English queen did not expect, however, was that her Scottish cousin would realise that marriage with the Infante of Spain, Don Carlos, was a dead letter, and that she might instead woo the hapless Darnley. In doing so, Mary could bring under her own aegis a presumptive (and presumptuous) heir to Scotland and a rival for the English succession. Darnley, who was only a teenager, and one inflated with a grandiose sense of self-importance by his parents, could hardly believe his luck. When the chance of a crown was dangled before him – and a beautiful, willowy, and willing bride offering it – he leapt at it, and the pair had been wed on 29 July 1565, in the teeth of a panicked Elizabeth’s commands that he cease his sudden relationship and return to England.

Yet Mary Queen of Scots was no lovelorn girl. With Darnley safely married to her, she moved to clip his wings before they could flutter. As the queen’s partisan, Lord Herries, was later to report, ‘[Darnley] had done some things and signed papers without the knowledge of the Queen . . . she thought although she had made her husband a partner in the government, she had not given the power absolutely in his hands . . . [her] spirit would not quit [relinquish] any of her authority . . . And then, lest the King should be persuaded to pass gifts or any such thing privately, by himself, she appointed all things in that kind should be sealed with a seal.’2

Mary, it seems, had married a stud horse who would allow her to retain the Stuart name, and who might be usefully and publicly subordinated as a dynastic rival. She had not married, and nor did she want a superior partner in government. To Darnley’s credit, he did manage to perform his primary function: his wife’s pregnancy was apparent by the end of the year, with the baby born in Edinburgh Castle on 19 June 1566. A thin membrane about his head, supposedly, augured well; it was variously interpreted as offering protection from fairies, promising good luck, and indicating an ability to travel quickly. Soon enough, the English envoy, Henry Killigrew, was reporting that the child was ‘well-proportioned and like to prove a goodly prince’.3

It is not clear when Darnley realised he had been had, and that he was unlikely either to be taken seriously as a monarch or granted that peculiarly Scottish prize, the Crown Matrimonial (which would enable him to rule in his own right). At first, all the signs that the callow and easily-led youth would be a king in more than name had been good: he had been given the title – albeit by his wife’s proclamation rather than by the Scottish parliament – and his image and name had appeared on coinage. But realise he did, and that realisation provoked a simmering fury. Worse, it acted as an invitation to malcontents who resented their queen’s reliance on foreign, Catholic servants – chiefly on the upstart Savoyard musician, David Riccio. The details of the horrific result are well known enough to hardly require rehearsal: Darnley involved himself with a group of plotters who intruded on the heavily pregnant queen’s private apartments at the Palace of Holyroodhouse, dragged Riccio away from her, and stabbed him to death. Although Mary rallied and – to assure the world of her unborn child’s legitimacy – embraced her treacherous husband back into the fold, the marriage was effectively over. What followed, and what resulted in Darnley sulking in his rooms at Stirling Castle during James’s baptism, was a hollow pretence, characterised by mutual suspicion and endless scheming for possession of the infant. It was such scheming, indeed, that had led Mary in September 1566 to place their son first under the ‘government’ of the Countess of Moray, and the following March under the custodianship of John Erskine, Earl of Mar, in both cases behind Stirling’s thick walls. Mar, for his trouble, had his keepership of the castle made hereditary – an act which would have consequences for James and his own wife’s relationship.

If the marital breakdown of the royal couple was not enough to add an unpleasant undertone to the glitzy celebrations of the prince’s baptism, the religious and wider political divisions were worse. Mary was, of course, a committed Catholic. But the Scotland to which she had returned in August 1561, following her time in France, had been effectively taken over by a Protestant cabal calling themselves the Lords of the Congregation: a group which included her illegitimate half-brother, James Stuart, later Earl of Moray. These men had risen in rebellion in the late 1550s, their pockets weighted – though not as much as they would have liked – with English gold, against Mary’s mother and regent, Marie of Guise. Marie’s subsequent mistake had been to assume that Scottish nationalism was simply antipathy towards the English, and that any moves to counter aggression from the southern kingdom would win Scottish hearts. In response to her English-funded rebels, she had therefore flooded Scotland with French soldiers and installed trusted Frenchmen in government – an act which certainly helped her anti-English and anti-Protestant narrative, but which indicated to a significant number of Scots that their country would become a French satellite (a prospect as alarming as English domination). A state of conflict ensued, fought between the rebels – who could claim to stand against Francophilia – and the regency government, which looked increasingly likely to sell Scotland’s independence to the...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 7.9.2023 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | 16pp b/w plates |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Archäologie | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Neuzeit (bis 1918) | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Kulturgeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | balanced views • Biography • British history • fresh light • Great Britain • James VI • James VI and I • King James • laid bare • Leanda de Lisle • misunderstood • narrative history • new biography • Non-fiction • Other Boleyn Girl • Philipa Gregory • popular historian • Popular History • Primary Sources • revisionist history • Royal Family • Scotland • Scotland and England • Scottish History • scottish monarchy • scurrilous • sexual politics • Steven Veerapen • Stewart Kings • true account • True story • Union of the Crowns • United Kingdom |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78885-640-6 / 1788856406 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78885-640-9 / 9781788856409 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 13,1 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich