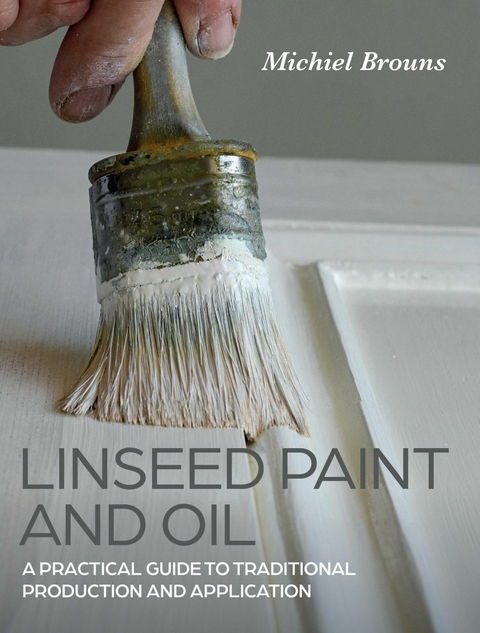

Linseed Paint and Oil (eBook)

112 Seiten

The Crowood Press (Verlag)

978-0-7198-4226-9 (ISBN)

Michiel Brouns has worked in historic building preservation for twenty years, and established the linseed paint company Brouns & Co. in 2011. He has worked on high-profile restoration projects including Woburn Abbey, Chatsworth House and Windsor Castle. He is widely regarded as one of the few experts in linseed paint, and he delivers presentations to architects across the UK and USA, approved by RIBA, AIA, ICAA and ACBA.

Linseed paint helped protect wood and iron for many hundreds of years. Since the advent of petrochemical paints, however, the industry has largely forgotten the value of traditional alternatives. This book provides an insight into the benefits of linseed paint for architects, professional decorators, restoration professionals and DIY enthusiasts alike. It describes in detail the unique role linseed paint plays in the preservation of historic buildings, including: What linseed paint is, what the ingredients are and how it is made, the benefits of linseed paint and how it functions on a molecular level, how linseed paint can play a pivotal role in reducing microplastics and making the building and restoration industries more sustainable and detailed step-by-step instructions for applying linseed paint to a variety of surfaces

Chapter One

The History of Linseed Paint

Linseed oil is often said to be as old as the hills. Though it probably isn’t quite that old, there is certainly enough evidence to link it back to multiple ancient civilisations, including Ancient Egypt.

In 2013, the UK’s Channel 4 aired a documentary about the remains of Tutankhamun called Tutankhamun: The Mystery of the Burnt Mummy. In particular, the documentary set out to address the question of why the king’s remains are so badly charred, and why this appears to have happened while the mummy was sealed inside the coffin.5 After much careful analysis, the experts determined that the reason for the charring was because the mummification of Tutankhamun’s remains had to happen quickly – most likely because of war or civil unrest – and those who carried out the process were therefore careless. The experts’ theory was that rags soaked with linseed oil, which had been used in the process, were left on the mummy and caught fire, causing the remains to burn inside the sarcophagus.

Not all scholars agree on this and Professor Ben Sherman from the University of Bradford had his doubts when I discussed it with him. Though it’s certainly an interesting theory, whether or not linseed oil was used on that particular occasion as part of the process is more or less irrelevant. What does matter, and what is known without any doubt, is that the use of linseed oil and paint can be traced back for thousands of years.

How is Linseed Paint Made?

Historically, linseed paint was mixed in individual quantities by hand. In the 1723 book, The Art of Painting in Oyl, John Smith wrote:

Lay … two Spoonfuls of the colour on the midst of your Stone, and put a little Linseed Oyl to it, … then with your Muller mix it together … ’till it come to the Consistence of an Oyntment … and smooth as the most curious Sort of Butter.6

In essence, modern linseed paint production has not changed a great deal from these instructions. Though, of course, when making linseed paint in industrial quantities, a muller and stone is obviously not an efficient way of doing things. On an industrial scale, the muller and stone are replaced with a triple roller mill. Though significantly larger and more sophisticated, a triple roller mill still achieves the main purpose in exactly the same way – by grinding pigment into boiled linseed oil to form a paste.

Quicker production methods do exist, such as using high-speed machinery to stir oil and pigments together to disperse the pigment. However, this does not result in the same smooth, fine texture as is achieved by the grinding process. Another method involves what is essentially a big column drill with an extended head that uses ball bearings to grind pigment into oil, but this method would only be able to create the correct consistency with days and days of work. If that wasn’t reason enough for this method to be considered unworkable, the pressure released by the drill would heat the oil and pigments to such an extent that they would need to be left to cool every couple of hours. Arguably, this is one of those instances where the original method just can’t be beaten, though obviously it’s been refined over the centuries as new technology and equipment has come along.

Once the initial paste of pigment and boiled linseed oil has been created, additional pigment pastes can be mixed in to achieve the correct hue. Finally, more boiled oil is added in order to reach the desired consistency. Real linseed paint should only contain a mix of natural pigments without any synthetic colourants, as these are not stable enough in boiled linseed oil. Modern linseed oil generally also contains a small proportion of natural solvents (such as balsam turpentine) and drying agents.

The Early History of Linseed Oil

Early history in Europe

It all began with the flax plant, officially known as Linum usitatissimum. This multipurpose plant is not only responsible for linseed oil, which is derived from the seeds, but also linen, which is made from the plant fibres.

Growing and cultivating flax plants is an ancient activity, as is the making of linen. Evidence of linen-making has been found by archaeologists in Neolithic settlements in the Jura Mountains of Switzerland.7 With the knowledge we have now about the ancient use of linseed oil, we can safely assume that wherever there was linen production, there was also linseed oil. Over the centuries, the growing and processing of flax became a commercially minded operation. By the Middle Ages it was big business, especially in the lower Rhine region of Germany. At the time, Germany made and exported more linen than anywhere else in the world.8

This is also the point at which linseed oil became widely used as a building product. Evidence of this can be seen at the Museum of Cultural History in Lund, Sweden, which collects old buildings from all over the country and reconstructs them together in one place for people to visit. Amongst these buildings are cabins from the 1300s, which still include some of the original timbers. There is evidence to suggest that these timbers have only ever been treated with pine tar and linseed oil.

The Art of Painting in Oyl.

We know from the paintings of Vermeer and Rembrandt that the use of linseed paint was very common in the art world by the 1600s. However, by this point it was also being widely used in building applications outside Scandinavia, certainly in Amsterdam, Delft and Leiden. By the late 1600s and early 1700s, this had spread even further and linseed paint was being used extensively in England. It was at this time that John Smith published the first known account of how to make and apply linseed oil. My copy of his book The Art of Painting in Oyl is a fifth edition and was published in 1723 (the first edition was published in 1676). Smith wrote:

The whole Treatise being to full Compleat, and to exactly fitted to the meanest Capacity, that all Persons whatsoever, may be able by these Directions, to Paint in Oyl Colours all manner of Timber work; that require either Use, Beauty of Preservation, from the violence or Injury of the Weather.9

Though Germany dominated the flax trade early on, by the sixteenth century there was a wide corridor of flax production stretching from western Switzerland to the Rhine, up to Denmark and Sweden.10 The huge trade in flax, linen and linseed oil would have meant that the people who lived in these areas were hugely familiar with linseed oil and its uses.

It’s only natural, then, that when European nations began expanding into the ‘new world’ of the Americas, the people that travelled there took their knowledge of linseed oil with them.

Reaching the New World

By the late 1500s, Sweden, the Netherlands (Holland), France and Spain were battling for dominance, both in terms of religion and land. This quest eventually led them to expand into the ‘New World’ of the Americas. Spain began to dominate the largest part of South and middle America, but Sweden and the Netherlands were more interested in parts of North America, as was France. France was on the rise as a world power and had its sights firmly fixed on what is now the Hudson Bay area, along with most of eastern Canada. The most effective way for cultures, habits, languages and architecture to spread is by the movement of people. As European settlements expanded into other parts of the world, they took all these things with them.

The later 1500s and early 1600s were a fairly turbulent period in terms of religion, with convictions and affiliations frequently changing, especially in England. A group of persecuted Protestants fled Yorkshire, Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire to seek religious sanctuary in Leiden, in the Netherlands. This religious persecution fuelled the expansion of Protestant Northern European nations into the New World, and the Leiden Protestants set sail in 1620, first on the Speedwell from Delfshaven, in the Netherlands, then onwards on the Mayflower from England.

Map depicting the journey of the Mayflower and first European settlement areas.

The Mayflower is best known for the Pilgrims, but at least half of the passengers on board were classified as ‘strangers’. These strangers were non-Puritans simply hoping to start a better life in what they thought would be Virginia.11 Many of these individuals had been selected on the basis of their usefulness and physical fitness. This meant that they were disproportionately young men, most barely out of their teens, who were skilled in rough trades such as carpentry, thatching and general building work. Many of these strangers would therefore have been well-practised in using linseed oil and its derivatives for building applications. Indeed, on their initial voyages they took some essential tools and building materials with them, including linseed oil and pigments.

When the settlers reached America and established the Plymouth Colony, linseed oil was one of the building products they used to do this. Not only would it likely have been used for timber preservation, but Patricia and Scott Deetz also note in their book The Times of their Lives: Life, Love and Death in Plymouth Colony: ‘the house’s tiny, barely translucent windows were made of linseed-coated parchment’.12

It was not only persecuted Protestants from Europe who took linseed oil with them to the Americas. By the late seventeenth century, northern Ireland had emerged as a leader...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 14.6.2023 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Freizeit / Hobby ► Hausbau / Einrichten / Renovieren |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Freizeit / Hobby ► Heimwerken / Do it yourself | |

| Schlagworte | algae • Application of paint • Applying paint • Brushes • Cleaning brushes • Colours • decoration • Exterior features • hardwood • Heritage Buildings • Heritage skills • Heritage trades • Historic Buildings • Internal walls • linseed oil • listed buildings • Masonry • metal surfaces • Modernist Movement • mould • painting • Period features • Pigments • Plastic paint • Preparation • Preparing the surface • Rot • Rotting timber • softwood • Storing paint • Tar oil • timber • Window frames • Wooden doors |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7198-4226-3 / 0719842263 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7198-4226-9 / 9780719842269 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich