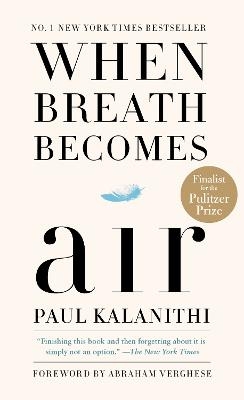

When Breath Becomes Air

Random House USA Inc (Verlag)

978-1-9848-0182-1 (ISBN)

NAMED ONE OF PASTE'S BEST MEMOIRS OF THE DECADE - NAMED ONE OF THE BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR BY The New York Times Book Review - People - NPR - The Washington Post - Slate - Harper's Bazaar - Time Out New York - Publishers Weekly - BookPage

Finalist for the PEN Center USA Literary Award in Creative Nonfiction and the Books for a Better Life Award in Inspirational Memoir

At the age of thirty-six, on the verge of completing a decade's worth of training as a neurosurgeon, Paul Kalanithi was diagnosed with stage IV lung cancer. One day he was a doctor treating the dying, and the next he was a patient struggling to live. And just like that, the future he and his wife had imagined evaporated. When Breath Becomes Air chronicles Kalanithi's transformation from a naïve medical student "possessed," as he wrote, "by the question of what, given that all organisms die, makes a virtuous and meaningful life" into a neurosurgeon at Stanford working in the brain, the most critical place for human identity, and finally into a patient and new father confronting his own mortality.

What makes life worth living in the face of death? What do you do when the future, no longer a ladder toward your goals in life, flattens out into a perpetual present? What does it mean to have a child, to nurture a new life as another fades away? These are some of the questions Kalanithi wrestles with in this profoundly moving, exquisitely observed memoir.

Paul Kalanithi died in March 2015, while working on this book, yet his words live on as a guide and a gift to us all. "I began to realize that coming face to face with my own mortality, in a sense, had changed nothing and everything," he wrote. "Seven words from Samuel Beckett began to repeat in my head: 'I can't go on. I'll go on.'" When Breath Becomes Air is an unforgettable, life-affirming reflection on the challenge of facing death and on the relationship between doctor and patient, from a brilliant writer who became both.

Paul Kalanithi was a neurosurgeon and writer. He grew up in Kingman, Arizona, and graduated from Stanford University with a BA and MA in English literature and a BA in human biology. He earned an MPhil in history and philosophy of science and medicine from the University of Cambridge and graduated cum laude from the Yale School of Medicine, where he was inducted into the Alpha Omega Alpha national medical honor society. He returned to Stanford to complete his residency training in neurological surgery and a postdoctoral fellowship in neuroscience, during which he received the American Academy of Neurological Surgery's highest award for research. He died in March 2015. He is survived by his large, loving family, including his wife, Lucy, and their daughter, Elizabeth Acadia.

Part I In Perfect Health I Begin The hand of the Lord was upon me, and carried me out in the spirit of the Lord, and set me down in the midst of the valley which was full of bones, And caused me to pass by them round about: and, behold, there were very many in the open valley; and, lo, they were very dry. And he said unto me, Son of man, can these bones live? -Ezekiel 37:1-3, King James translation I knew with certainty that I would never be a doctor. I stretched out in the sun, relaxing on a desert plateau just above our house. My uncle, a doctor, like so many of my relatives, had asked me earlier that day what I planned on doing for a career, now that I was heading off to college, and the question barely registered. If you had forced me to answer, I suppose I would have said a writer, but frankly, thoughts of any career at this point seemed absurd. I was leaving this small Arizona town in a few weeks, and I felt less like someone preparing to climb a career ladder than a buzzing electron about to achieve escape velocity, flinging out into a strange and sparkling universe. I lay there in the dirt, awash in sunlight and memory, feeling the shrinking size of this town of fifteen thousand, six hundred miles from my new college dormitory at Stanford and all its promise. I knew medicine only by its absence-specifically, the absence of a father growing up, one who went to work before dawn and returned in the dark to a plate of reheated dinner. When I was ten, my father had moved us-three boys, ages fourteen, ten, and eight-from Bronxville, New York, a compact, affluent suburb just north of Manhattan, to Kingman, Arizona, in a desert valley ringed by two mountain ranges, known primarily to the outside world as a place to get gas en route to somewhere else. He was drawn by the sun, by the cost of living-how else would he pay for his sons to attend the colleges he aspired to?-and by the opportunity to establish a regional cardiology practice of his own. His unyielding dedication to his patients soon made him a respected member of the community. When we did see him, late at night or on weekends, he was an amalgam of sweet affections and austere diktats, hugs and kisses mixed with stony pronouncements: "It's very easy to be number one: find the guy who is number one, and score one point higher than he does." He had reached some compromise in his mind that fatherhood could be distilled; short, concentrated (but sincere) bursts of high intensity could equal . . . whatever it was that other fathers did. All I knew was, if that was the price of medicine, it was simply too high. From my desert plateau, I could see our house, just beyond the city limits, at the base of the Cerbat Mountains, amid red-rock desert speckled with mesquite, tumbleweeds, and paddle-shaped cacti. Out here, dust devils swirled up from nothing, blurring your vision, then disappeared. Spaces stretched on, then fell away into the distance. Our two dogs, Max and Nip, never grew tired of the freedom. Every day, they'd venture forth and bring home some new desert treasure: the leg of a deer, unfinished bits of jackrabbit to eat later, the sun-bleached skull of a horse, the jawbone of a coyote. My friends and I loved the freedom, too, and we spent our afternoons exploring, walking, scavenging for bones and rare desert creeks. Having spent my previous years in a lightly forested suburb in the Northeast, with a tree-lined main street and a candy store, I found the wild, windy desert alien and alluring. On my first trek alone, as a ten-year-old, I discovered an old irrigation grate. I pried it open with my fingers, lifted it up, and there, a few inches from my face, were three white silken webs, and in each, marching along on spindled legs, was a glistening black bulbous body, bearing in its shine the dreaded blood-red hourglass. Near to each spider a pale, pulsating sac breathed with the imminent

| Erscheinungsdatum | 17.12.2018 |

|---|---|

| Vorwort | Abraham Verghese |

| Verlagsort | New York |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Maße | 105 x 174 mm |

| Gewicht | 125 g |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Briefe / Tagebücher | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik ► Politik / Gesellschaft | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie ► Esoterik / Spiritualität | |

| Schlagworte | autobiographies • Autobiography • Being Mortal • Biographies • Biography • Cancer • cancer books best sellers • cancer memoir • Death • death and dying • doctors • Dying • Grief • Health • Inspirational • inspirational books • Meaning of life • Medical • medical books • Medicine • Memoir • Memoirs • Mental Health • Mortality • Mourning • Neuroscience • neurosurgeon • nonfiction best sellers • ny times best seller list • Philosophy • Sociology • terminal illness • top biographies • True stories • True story • when breath becomes air by paul kalanithi |

| ISBN-10 | 1-9848-0182-1 / 1984801821 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-9848-0182-1 / 9781984801821 |

| Zustand | Neuware |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

aus dem Bereich