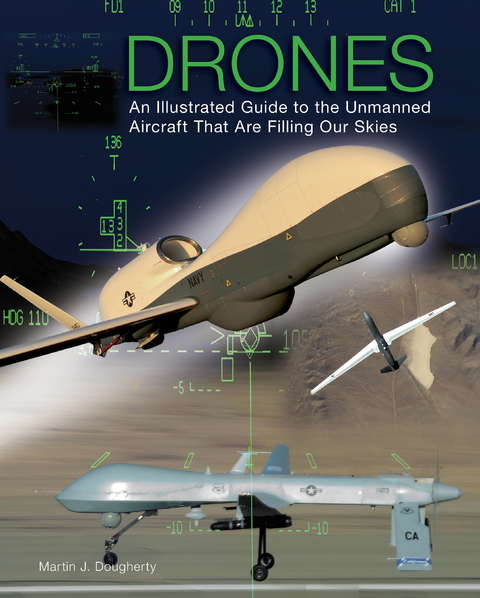

Drones (eBook)

224 Seiten

Amber Books Ltd (Verlag)

978-1-78274-300-2 (ISBN)

Used for reconnaissance work and mapping as well as launching missiles, drones can fly autonomously or be controlled by remote control. Peering into a volcano about to erupt, checking how fast a forest fire is spreading, exploring the wreck of a sunken ship, charting your enemy's position and taking out a military target-these are just some of the uses of drones today.

From drones the size of a fingertip to drones that can carry soldiers, from single rotorcraft to multi-rotorcraft to propeller craft drones, Drones expertly examines these complex vehicles, which are not only very different from manned aircraft, but also very different from each other.

Illustrated with more than 220 colour photographs and artworks, Drones is an exciting, accessibly written work about the latest in military and civilian aviation technology.

Little more than ten years ago drones were barely used, but now more than 50 countries have them in service and they are not only changing how wars are fought but how crops are sprayed, how underwater pipelines are monitored and even how sports events are filmed. If it's too risky to send a manned aircraft to survey the intensity of a hurricane or a combat zone, or too costly for conservation wardens to chart the movement of wildlife, drones can be used. Used for reconnaissance work and mapping as well as launching missiles, drones can fly autonomously or be controlled by remote control. Peering into a volcano about to erupt, checking how fast a forest fire is spreading, exploring the wreck of a sunken ship, charting your enemy's position and taking out a military target-these are just some of the uses of drones today. From drones the size of a fingertip to drones that can carry soldiers, from single rotorcraft to multi-rotorcraft to propeller craft drones, Drones expertly examines these complex vehicles, which are not only very different from manned aircraft, but also very different from each other. Illustrated with more than 220 colour photographs and artworks, Drones is an exciting, accessibly written work about the latest in military and civilian aviation technology.

Introduction

Not very many years ago, few people had even heard of drones. Most of those who had would probably have an idea from science fiction or techno-thrillers about what a drone was and what it might be capable of, but no real knowledge. Yet, in just a few years, drones have gone from obscurity to near-constant media attention. We hear of drone strikes and drone surveillance in the world’s trouble zones, and of drones delivering packages – even pizza – in the commercial world.

A surprising number and range of users have been operating drones for some time, although the rest of the world has known little about it. Outside of the military, drones have been used for research purposes, or to monitor the environment. Commercially available drones can now be bought at quite a cheap price by private users for recreational purposes.

Yet, in truth, there is nothing really new about the idea of a remotely operated vehicle. The word ‘drone’ has entered the popular vocabulary, but long before this happened users were flying remote-controlled aircraft and helicopters, or racing radio-controlled cars. Remotely controlled weapons have been in use for several years – although not always with a great deal of success. It is, however, debatable whether these were, strictly speaking, drones.

What is a Drone?

One useful definition of a drone is a pilotless aircraft that can operate autonomously, i.e. one that does not require constant user control. This means that traditional radio-controlled aircraft and the like are not, in the strictest sense, drones. Nor are many underwater Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs), and not only because they are not aircraft. In fact, many recreational ‘drones’ are not really drones, as they are semi-autonomous. However, it is useful to widen the definition of a drone somewhat in order to cover a range of similar vehicles that undertake the same role using broadly the same principles.

RQ-4 GLOBAL HAWK

SPECIFICATIONS: RQ-4 GLOBAL HAWK

Length: 14.5m (47ft 6in)

Wingspan: 39.8m (130ft 6in)

Height: 4.7m (15ft 4in)

Powerplant: Rolls-Royce North American F137-RR-100 turbofan engine

Maximum takeoff weight: 14,628kg (32,250lb)

Maximum speed: 574km/h (357mph)

Range: 22,632km (14,063 miles)

Ceiling: 18,288m (60,000ft)

Endurance: More than 34 hours

Operating a UAV is a complex business, which has been described as similar to flying a plane whilst looking through a straw. In addition to piloting the vehicle, operators must control cameras, radar and other instruments, and hand-off data to other users, making the operation of a large military UAV a multi-person task.

It is quite difficult to pin down a working definition of ‘drone’ that does not immediately founder on the rocks of the first exception it encounters. In theory, any remote-controlled aircraft can operate like a drone, inasmuch as it can be pointed in the right direction and set to fly straight and level. During this period, the operator can let go of the controls and the aircraft will go on its way without control input.

This is not really a drone operation, however. To be such, the aircraft would need to be able to make some decisions for itself. A simple autopilot that used the aircraft’s control surfaces to keep it on course might not qualify, but one that could be given a destination and fly the aircraft to it, possibly making course changes as necessary, would fit the common definition of a drone.

Some ‘drones’, especially those operated by the military, are primarily operated by a pilot from a ground station. They can undertake autonomous flight, but are normally under constant control. Military drones, such as Predator, require considerable piloting skills and push the boundaries of what is, and what is not, a drone. Indeed, many operators dislike the use of the term ‘drone’, as what they do is every bit as difficult as flying an aircraft that they are aboard.

HOW DRONES WORK

The majority of small UAVs resemble the miniature aeroplanes flown by radio-control enthusiasts for many years. There are more design options as size increases. The RQ-2 Pioneer at centre rear is essentially a conventional small aircraft whilst the RQ-15 Neptune at right rear is a flying boat designed to land on water.

AUTONOMOUS LANDING PROCEDURE

A US military Predator drone, flying under constant control by a ground operator, is not really a drone under the strict definition above. It is an Unmanned Air Vehicle (UAV), a term that its operators prefer in any case. Similarly, a remotely operated vehicle used for underwater operations – say inspecting deep-water pipelines – may be under constant control and would best be considered a Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) or an Unmanned Underwater Vehicle (UUV).

Missiles and torpedoes meet the definition of a drone in many ways. They can guide themselves, making decisions about flight path or direction of travel, and often operate autonomously. Some are manually guided or home in on a manually controlled targeting system, such as a laser designator. Missiles and torpedoes are not, however, normally considered to be drones, even though there are drones that fulfil a similar role.

Likewise, it can be difficult to decide whether a given vehicle is a drone or not by just seeing it in operation. A drone-like aircraft could be under constant manual control, perhaps by using a First-Person View (FPV) system. This is essentially a camera in the front of the vehicle that gives the operator a pilot’s view. A small aircraft-type ‘drone’ might be a traditional model aircraft, or might be flying under its own control using GPS guidance.

Thus the field of drone operations is rather complex and overlaps in some other areas. For our purposes it must suffice to use a fairly loose definition of the term ‘drone’. We shall therefore consider a drone to be any vehicle that has no pilot aboard, and which is capable of at least some autonomous functions that require onboard decision-making, and which does not obviously fall into some other category, such as a missile or a guided artillery shell.

Historical Attempts

Historically, there have been numerous attempts to create pilotless vehicles, mainly for military purposes. Among the more ludicrous was the idea of using ‘organic control’ in a missile. The organic control took the form of a pigeon trained to recognize a particular type of target and peck at it. The intrepid pigeon could then guide a missile to the target by pecking at a screen in the front of the missile, which was connected to the controls to allow corrections. With the missile centred on the target, the pigeon’s pecks would keep the missile on course; deviation would be corrected as the pecks moved further from the centre of the screen.

The development of electronic systems small enough to fit inside a missile ensured that organic control was abandoned in the early 1950s. It has not, strangely enough, been revisited.

Other attempts at creating autonomous vehicles, also originating in World War II, were more straightforward. The V1 ‘flying bomb’ was essentially a pilotless aircraft powered by a pulse-jet engine. It was of simple construction and cheap to build, but carried a significant warhead. The V1 had an autopilot of sorts, which kept it level, and a very simple inertial system that activated the dive mechanism. A small propeller on the front of the V1 was driven round by air passing over the nose. When the propeller reached a preset number of revolutions, the bomb would, in theory, have travelled the requisite distance and should begin its dive towards the target.

V1 FLIGHT PATH

In practice, the careful calculations used to determine the dive point were thrown out by headwinds, tailwinds or imprecision in the device, causing many V1s to fall long or short. A side wind would also send the device off course. It had no navigation system as such, merely being launched in the direction of the target. This also made the V1 vulnerable to interception by aircraft and ground-based guns, as it had to follow a straight course.

Lack of a true autopilot allowed the flying bomb to be defeated by either flying ahead of it so that the slipstream of an aircraft caused it to veer off course and crash, or by the rather more hands-on approach of tipping the wing while flying alongside. The warhead did still come down somewhere, but it could be sent off target and prevented from striking a densely populated area.

The Mistel

The V1 flying bomb was not a drone as such, nor was it a missile. It can be considered a precursor to the modern military drone and missile, and helped prove the concept was workable. Another attempt at the same goal was the German ‘Beethoven Device’, a composite aircraft created from a single-seat fighter riding atop a larger aircraft. The latter, known as the ‘Mistel’, was packed with explosives and flown by remote control from the smaller aircraft.

The Mistel was usually a light bomber, such as a Ju-88, although various aircraft were used. Often these were obsolete designs, the intent being to obtain some useful...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 17.9.2015 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik ► Allgemeines / Lexika |

| Natur / Technik ► Fahrzeuge / Flugzeuge / Schiffe ► Luftfahrt / Raumfahrt | |

| Natur / Technik ► Fahrzeuge / Flugzeuge / Schiffe ► Militärfahrzeuge / -flugzeuge / -schiffe | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Militärgeschichte | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| Schlagworte | Afghan • airstrike • Control • drone • hellfire • Pakistan • Predator • remote • Search • seek • Strike • Surveillance • Track • underwater |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78274-300-6 / 1782743006 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78274-300-2 / 9781782743002 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 65,4 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich