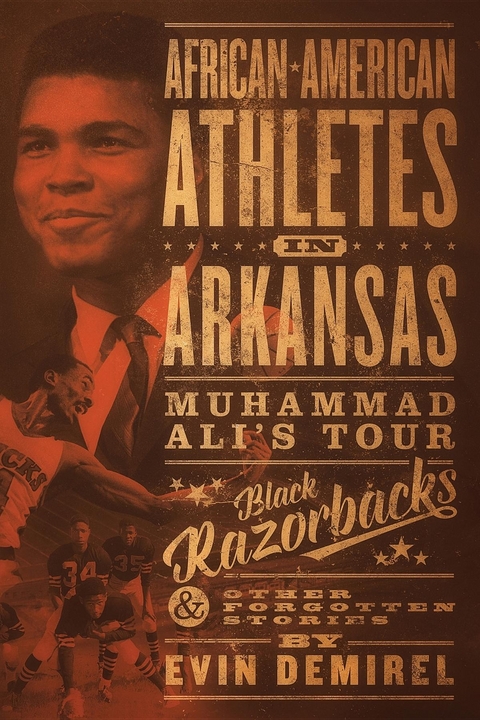

African-American Athletes in Arkansas (eBook)

202 Seiten

Publishdrive (Verlag)

978-0-9990083-2-4 (ISBN)

Sports has long been a powerful agent for change in American society. For the first time, the heritage of one region is examined through these lens. African-American Athletes in Arkansas brings to light forgotten figures and cultural giants who helped change the nation. These narrative non-fiction, primary sourced stories include:

1) An in-depth look at the evolution of various strands of black nationalism as seen through Muhammad Ali's college lecture tour in Arkansas

2) A national assessment of the lingering issue of integrating the sports records of all-black schools with those of their historical all-white counterparts

3) The inspiring story behind NBA pioneer 'Sweetwater' Clifton, who grew up near the Delta, attended DuSable High in Chicago and then starred for the New York Knicks

4) The college football boycott of the 'Black 14' in Wyoming, which thrust issues of race relations, civil rights and sports into the national limelight

5) The would-be Razorback pioneer Eddie Miles, who went on to star for Seattle University and the Detroit Pistons

6) How Arkansan African Americans helped fuel the Green Bay Packers' NFL dynasty of the 1960s

7) How Satchel Paige, the great Negro Leagues icon, and Dizzy Dean, the St. Louis Cardinals superstar, helped lay the groundwork for the Civil Rights Movement

9) How black Arkansas natives helped power a championship baseball team against all-white competition in Butte, Montana in the Great Depression

This one-of-a-kind anthology, which also showcases an original feature on Fayetteville's forgotten 'Black Razorbacks' of the Great Depression, includes articles from Slate, Arkansas Life, the Arkansas Times and more. These stories break new ground, illuminating some of the profound socioeconomic, educational and religious forces which shape the lives of all Americans - black, white, Hispanic, Southerner and non-Southerner alike - to this day.

Sports has long been a powerful agent for change in American society. For the first time, the heritage of one region is examined through these lens. African-American Athletes in Arkansas brings to light forgotten figures and cultural giants who helped change the nation. These narrative non-fiction, primary sourced stories include:1) An in-depth look at the evolution of various strands of black nationalism as seen through Muhammad Ali's college lecture tour in Arkansas2) A national assessment of the lingering issue of integrating the sports records of all-black schools with those of their historical all-white counterparts The inspiring story behind NBA pioneer "e;Sweetwater"e; Clifton, who grew up near the Delta, attended DuSable High in Chicago and then starred for the New York Knicks4) The college football boycott of the "e;Black 14"e; in Wyoming, which thrust issues of race relations, civil rights and sports into the national limelight5) The would-be Razorback pioneer Eddie Miles, who went on to star for Seattle University and the Detroit Pistons6) How Arkansan African Americans helped fuel the Green Bay Packers' NFL dynasty of the 1960s7) How Satchel Paige, the great Negro Leagues icon, and Dizzy Dean, the St. Louis Cardinals superstar, helped lay the groundwork for the Civil Rights Movement9) How black Arkansas natives helped power a championship baseball team against all-white competition in Butte, Montana in the Great DepressionThis one-of-a-kind anthology, which also showcases anoriginal featureon Fayetteville's forgotten "e;Black Razorbacks"e; of the Great Depression, includes articles from Slate, Arkansas Life,the Arkansas Times and more. Thesestoriesbreak new ground,illuminatingsome of theprofoundsocioeconomic, educational and religiousforceswhich shape the lives of allAmericans - black, white, Hispanic,Southerner and non-Southerner alike-to this day.

Integrate the Record BooksWhy black high school athletes from the Jim Crow era have been denied their place in history. The Original Black Razorbacks Decades before Arkansas football officially integrated, a team of African Americans played on university grounds, wore Hog uniforms and played against all-white teams. It appears University of Arkansas coaches even trained them. Black Razorback Fans of the Jim Crow Era: A Forgotten Past The story of African-American fans who cheered all-white Hogs in Fayetteville and Little Rock.Black Arkansans Fueled the NFL’s Evolution Arkansans like Faulkner County native Elijah Pitts formed the backbone of the first Super Bowl champions, the Green Bay Packers. The Pine Bluff Native Whose Protest Rocked the College Football World Arkansan Ivie Moore was one of 14 Wyoming football players who in 1969 ignited a national civil rights debate involving students’ rights, the power of the athletic department and free expression.The Sweetest Thing A major motion picture involving Ludacris and Nathan Lane is in the works about Arkansas native Nathaniel “Sweetwater” Clifton, a “Jackie Robinson of the NBA.”From Lonoke County to Legend Nat Clifton rose from life in Great Depression-era Lonoke County to star for the New York Knicks as one of the first African Americans in the NBA.Nolan Richardson Enters the Hall of Fame Evin Demirel’s on-site report from the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame induction of the greatest Razorback basketball coach. The Enduring Legacy of Little Rock’s Hilarious Jesters While history books tend to focus on the landmark events leading to integration, there were other moments that went largely undocumented—such as those that occurred during a pick-up game of basketball.Eddie Boone: First Black Coach in the Arkansas Activities Association Years before he coached Houston Nutt at LR Central, Boone led all-black basketball teams out of Menifee into the Ozark mountains. There they played communities where hardly any African Americans had been seen before.The Would-Be Razorback Pioneer: Eddie Miles In the late 1950s, Razorback basketball coaches almost made North Little Rock’s Eddie Miles (a future NBA No. 4 draft pick) the first official black Razorback.Photos from the Scrapbook Dizzy Dean & Satchel Paige As a St. Louis Cardinal superstar, Logan County native Dizzy Dean teamed up with Satchel Paige, the greatest Negro Leagues pitcher, to set the stage for the Civil Rights movement. Fort Smith’s Black Baseball Heritage Satchel Paige once dueled with Ft. Smith native Louis McGill in Arkansas. McGill’s son, George McGill, discusses his father’s adventures playing minor league and community ball in Sebastian and Washington counties. In Montana, Arkansans Played Key Role In Success Of Segregated Baseball Team The story of a group of Arkadelphia natives who formed a talent pipeline to Butte, MT of all places…Vanishing ActIn 1985, Arkansan African Americans helped push the Razorbacks to the College World Series with a record five black starters. Decades later, black baseball statewide is dying. What happened? Muhammad Ali in Arkansas At the height of the Vietnam War, the century’s most controversial and beloved athlete pulled no punches in Little Rock, Pine Bluff and Fayetteville. Acknowledgments EndnotesIndex

THE ORIGINAL BLACK RAZORBACKS

DECADES BEFORE OFFICIAL INTEGRATION, A TEAM OF AFRICAN AMERICANS PLAYED ON UNIVERSITY GROUNDS, WORE RAZORBACK FOOTBALL UNIFORMS AND COMPETED WITH WHITES. IT APPEARS UNIVERSITY OF ARKANSAS COACHES EVEN TRAINED THEM.

Razorback linebacker Brooks Ellis had lived in Fayetteville his whole life, but had never heard of the “Black Razorbacks.”1 Not that he’s to blame. Hardly anyone, after all, remembers the group of young African Americans who donned old Razorback and Fayetteville High jerseys during the Great Depression and played football across Fayetteville and the region. These northwest Arkansas locals, who represented their region against other all-black teams from Russellville, Arkansas to Joplin, Missouri, formed a kind of regional “Negro leagues of football” that is all but forgotten by Arkansans today.

Their story upends common modern conceptions of athletic segregation in the Old South. Not only did this team scrimmage against white players from a then-segregated Fayetteville High School, but they did so on the grounds of the segregated University of Arkansas itself—under the watch and tutelage of white Razorback football coaches. Moreover, the white players often visited Fayetteville’s all-black neighborhood to play there. “That’s awesome to hear about,” Ellis said as he sat in the Razorbacks locker room in August 2015. His alma mater, Fayetteville High School, stood less than a mile away.

Ellis noted Fayetteville High School had, in 1954, become the first high school in Arkansas to publicly announce its desegregation—“I take a little pride in that”—but the fact that African Americans were regularly playing against the all-white Bulldogs decades before that was news to him. He added, “It would be cool to learn more about, obviously.”

Let us begin, then.

Much of the Black Razorbacks’ story comes to us from accounts of their games buried in the archives of the Northwest Arkansas Times, a newspaper run by civic leader Roberta Fulbright—the mother of U.S. senator J. William Fulbright. The most detailed known retrospective comes from Arthur Friedman, a white Fayetteville resident who attended Fayetteville High School in the early 1930s.

He often watched the Black Razorbacks’ scrimmages and games, and considered those times “the highlight of my growing-up years and school,” he wrote in a 1985 Northwest Arkansas Times article.2 Indeed he considered the African-American players, many around his age, as friends.

All-black high schools proliferated in the east, central and south parts of Arkansas, but none existed in its northwest corner. The teenage African Americans in Washington and Benton counties seeking high school education had to move to Fort Smith to attend Lincoln High School, or relocate to more distant all-black schools in towns like Hot Springs.

The lack of educational resources for older black students in northwest Arkansas, in part, reflected the overall scarcity of blacks in the area. But it also represented the state’s allocation of fewer resources to its minority citizens. Consider that in 1928-29, the state spent an average of $35.05 per white student in its public schools compared to $14.38 per black student, according to Educating the Masses: The Unfolding History of Black School Administrators in Arkansas, 1900–2000.3

Some northwest Arkansas teenagers didn’t attend high school at all, or did so sporadically. This may explain why the Black Razorbacks sometimes scheduled early-afternoon weekday games during the school year. Arthur Friedman fondly recalled feigning sickness as a teen to skip school and attend one of those games against the all-black Joplin Pirates. He tried to keep it a secret from his parents, but his father figured out the ruse. He knew Friedman had been sent home for illness but never made it there. His suspicions of Friedman’s playing hooky were confirmed when he saw a recap of the Black Razorbacks’ game in the Fayetteville Daily Democrat the next morning.

Press coverage from white-owned and staffed newspapers, the only newspapers in northwest Arkansas, is a sign the Black Razorbacks benefited from biracial community support. So are reports citing attendance figures of up to 300 people for one of their home games. This is a large number of people in an era when Fayetteville’s overall population was less than 8,000 people, including a few hundred black residents. Certainly a large percentage, and possibly a majority, of the fans watching these all-black games would have been white residents.

In the Jim Crow era in many parts of the Old Confederacy, white spectators did not congregate at black sporting events. But Fayetteville was unusual. First of all, the University of Arkansas attracted more out-of-state professors, graduate students and administrators to this area compared to most parts of the state. Many came to Arkansas from regions outside of the South, places where Jim Crow laws did not so thoroughly permeate society.

Additionally, the town had so few black residents relative to whites that the two races could not, for practical reasons, separate even if that was what they wanted. Black Fayetteville natives often worked for and with whites in janitorial, food, hospitality and other service trades.

Although many black Fayetteville residents voluntarily lived in their own area of town, commonly known by white residents as Tin Cup4, they were not numerous enough to form a self-supporting community. So whites and blacks regularly commingled on the town square and in the poorer neighborhoods of south Fayetteville, and in and around the university.

Occasionally, white city leaders allowed official tribute to the contributions of black residents to their town’s heritage. One such instance came in 1928, when George Ballard, a local black poet, got permission to enter a float into the city’s 100-year anniversary parade on July 4. On this float named “Negroes of the Old South” rode some of the town’s eldest black residents, including “Uncle” Sam Young and Charles Richardson.

For at least a couple years around 1930, Friedman recalled, the Black Razorbacks were allowed to play on Fayetteville High’s Harmon Field. For how many years, specifically, is unknown. Fayetteville High first began using the field—then on the west side of town—in 1925.

In 1927, the city received funds from the New York City-based Harmon Foundation to upgrade the field.5 The son of a “Buffalo Soldiers” officer, the white William Harmon became a real estate developer and one of the nation’s foremost benefactors of African-American artists in the early 1900s. In the 1920s, he donated hundreds of thousands of dollars to municipal playgrounds across the nation.6 Sometimes the funds were for playgrounds meant to be enjoyed specifically by African-American children. This doesn’t appear to be the case with Fayetteville, though, considering the field’s location away from the black community and its status as the playing field of an all-white high school.

At some point in the early 1930s, “someone came up with a claim that the deed donating the area to the city of Fayetteville for recreational purposes stipulated that Negroes were never to be allowed to use the facilities,” Friedman recalled. And so, blacks were barred. (More than a little irony resides in the fact it was from a field named for, and funded by, one of the nation’s most egalitarian philanthropists.) To prevent a “racial hassle,” as Friedman recalled, the blacks moved to the center of the racetrack at the old Washington County Fairgrounds on Highway 62 West and there established a makeshift football field where they hosted out-of-town teams.

Since some white Fayetteville football fans personally knew the Black Razorbacks, it’s probable they were more likely to want to attend their games. According to Friedman, Fayetteville whites and blacks started playing each other in football in the 1920s. He recalled that as a child he and other white boys growing up on South Street played “weekly contests with the Black Razorbacks second team.” He recalled alternating playing “on the old Arkansas practice field directly east of Garland from the fieldhouse” and a “field strewn with rocks on Willow Avenue in the middle of Tincup [sic].”

On university grounds, the whites often routed the second-teamers, Friedman recalled. Sometimes the Black Razorbacks got so beat up they had to summon a local taxi driver named “Mud” Shelly to take them home. Shelly charged a quarter for the trip back to Tin Cup, making them pile en masse into his car or stand on the automobile’s running boards, Friedman recalled.

Friedman adds that the head football coach of the official Arkansas Razorbacks, Fred Thomsen, occasionally stopped by to scout these scrimmages. As a Nebraska native, Thomsen likely held a more permissive attitude toward interracial competition, and of donating old jerseys to African Americans co-opting his team’s name, than some natives of the South would have had. Nebraska had limited but unenforced Jim Crow rules,7 unlike the more elaborate discrimination laws in more southern Great Plains states and...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 12.7.2017 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Natur / Technik ► Fahrzeuge / Flugzeuge / Schiffe ► Fahrrad |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte | |

| Schlagworte | African-American • African-American athletes • Arkansans • Arkansas • Baseball • Basketball • black athletes • Black Studies • Football • Muhammad Ali • Race relations • razorbacks • Sports History • sports protests |

| ISBN-10 | 0-9990083-2-3 / 0999008323 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-9990083-2-4 / 9780999008324 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 9,3 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich