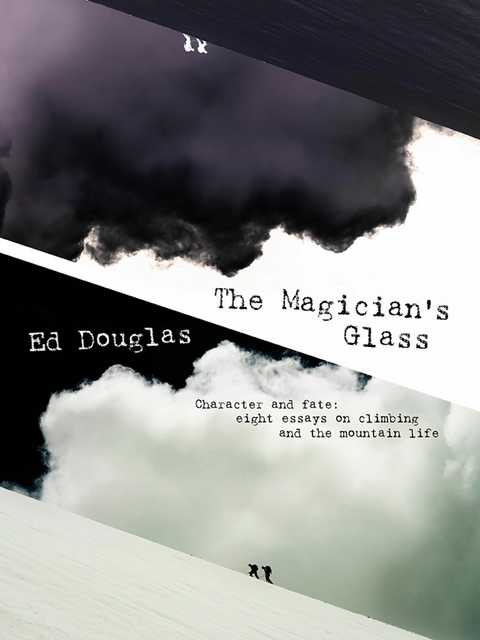

The Magician's Glass (eBook)

192 Seiten

Vertebrate Digital (Verlag)

978-1-911342-49-6 (ISBN)

Ed Douglas has been climbing for over thirty-five years and has been a writer and editor for the last thirty. He launched the magazine On The Edge while at university in Manchester, and has published eight books about mountains and their people. His books include biographies of Tenzing Norgay, rock-climbing visionary Ben Moon and the late British mountaineer Alison Hargreaves. His ghostwritten autobiography of Ron Fawcett, Rock Athlete, won the Boardman Tasker Award for Mountain Literature in 2010. Three of the essays in The Magician's Glass were either shortlisted for or won at the Banff Mountain Book Festival in Canada. Douglas's journalistic work most often appears in The Observer and The Guardian. He is the current editor of the Alpine Journal and lives in Sheffield with his wife Kate. They have two grown-up children.

Stefanie Egger struggles to her feet and disappears into the kitchen to fetch something she wants me to see. Now in her mid eighties, Steffi no longer moves easily, but her eyes are bright and her mind is sharp. She’s suffered more than many from life’s hardships, but this seems only to have whetted her dry sense of humour. Returning to the table, she lays in front of me a photograph taken of her family in 1930 when they still lived across the border in the Italian mountain town of Bolzano – called Bozen by its German-speaking population.

It’s a formal family portrait and the children are in their best clothes. Stefanie’s mother stands at her husband’s shoulder, her right arm resting on the back of his chair. Steffi sits upright on her father’s lap while her three brothers group around their mother. Franz, eight years old, is the only one of the brood with even the hint of a smile. Next to him is Hans, two years younger, with full lips and his head tilted to one side, looking a little dreamy. In front of him is the youngest boy, Toni, dressed in a checked wool jacket with a lick of blond hair over his forehead. He looks unusually focused for a child of four.

‘Toni was the darling,’ Steffi says without a trace of envy or resentment. ‘He could do no wrong. Toni war alles. He was everything. And if he wanted to be a mountain guide, then that was perfectly fine with my mother.’

While I scan the photograph, Steffi’s hand rests on another image, quite possibly the last ever taken of her brother, although this detail, like so much of Toni Egger’s last days, is now a matter of intense controversy. The image is taken from Cesare Maestri’s book Arrampicare è il Mio Mestiere – Climbing is My Trade – first published in 1961, two years after the two men, as the book claims, made the first ascent of a peak routinely described as the most beautiful and difficult in the world.

Reinhold Messner called Cerro Torre ‘a shriek turned to stone’, but that’s only when the wind blows. Under blue skies and high pressure it’s the closest you can imagine to mountaineering perfection, the Platonic ideal of what a climbing challenge should be. It provokes something akin to lust, which might explain that while gorgeous, the peak has borne witness to some morally questionable behaviour. As the famous French alpinist Lionel Terray put it, looking over at Cerro Torre from the summit of nearby Fitz Roy: ‘Now there’s a mountain worth risking one’s skin for!’

Through the 1950s, as ponderous national expeditions were planting flags on the summits of the world’s highest peaks, the true prophets of alpinism turned elsewhere to spy the future. Even though Lionel Terray, who had made the first ascent of Fitz Roy in 1952, dubbed Cerro Torre ‘impossible’, Patagonia looked a lot more like it than Everest. Cerro Torre drew the Italian climbers Walter Bonatti and Carlo Mauri, who made a bold attempt on the tower from the west. It also persuaded Cesarino Fava, an Italian émigré to Argentina, to write to the most famous climber from his home district, the man dubbed the Spider of the Dolomites: ‘Come here,’ he told Maestri, ‘You will find pane per i tuoi denti (bread for your teeth).’

Maestri acted on Fava’s invitation and when he returned to Italy and a hero’s welcome in 1959 after claiming Cerro Torre’s first ascent, the world of alpinism was duly impressed. At the age of twenty-nine he appeared to have jumped from being merely very good to reaching a place among the immortals. Terray wrote: ‘The ascent of Cerro Torre … by Toni Egger and Cesare Maestri, seems to me the greatest mountaineering feat of all time.’ Maestri himself loved making provocative or hyperbolic statements. ‘I wished to use climbing as a way of imposing my personality,’ he once said. Now, it seemed, he really had something to crow about. ‘This is my joy,’ Maestri said, responding to the Italian public who had come out to meet him. ‘And it helps to ease the pain of the loss of Toni.’

Stefanie Egger remembers those weeks in early 1959 when Toni was in Patagonia attempting Cerro Torre with Maestri – how her mother grew increasingly alarmed at the continuing silence of Toni, who in the past had been such a good correspondent. Stefanie was almost thirty and living in Innsbruck, working in the konditorei – the patisserie – of a local hotel, when the call came from her mother to tell her that her brother was dead.

‘You can imagine the impact, when a mother gets the message her son had died,’ Stefanie told me. ‘I think she thought about the possibility already, because it had been such a long time since we’d heard anything. When your child goes to the mountains, you have to consider the possibility.’

Stefanie went home to Lienz to comfort her grieving mother, and so was there when Maestri showed up at the door holding a bunch of white flowers, the colour, as Stefanie reminds me, of innocence and remembrance. Maestri told Stefanie’s mother what had happened: that the two men had been retreating in a storm; that Maestri was lowering Egger, who was looking for a bivouac site; that they both heard a rushing sound before an avalanche roared out of the cloud, sweeping Egger off the face and snapping the rope.

‘I didn’t believe his story,’ Stefanie says. ‘I believed they reached the top, but I knew there was something wrong with the story because nothing came back. Nothing. Not a sweater. Not his clothes. Not even his passport. Why? Why did nothing come back?’

Maestri attended a mass for Toni on 2 April and afterwards joined a group of Toni’s friends in the Rose pub, where he explained the circumstances of Toni’s death and promised to give a slide show about the ascent. It never happened and Stefanie hasn’t seen him since. (In the 1980s, Egger’s climbing club in Lienz invited Maestri, but he claimed his slides had been stolen.) The Egger family – Stefanie, her mother and her surviving brother, Hans – got on with their lives. For the climbing world, Toni became an abstraction, a two-dimensional character whose story was picked over for evidence in the growing controversy about Maestri’s claim. Even when Toni’s remains were found by the American climber Jim Donini in 1974, in a location well down the glacier that feeds from Cerro Torre and its satellites, Egger remained somehow remote, a handsome face in a black and white photograph from another era. His remarkable climbing career would soon be reduced to one simple question: How did he die?

While Toni Egger faded from view, Maestri’s book went through four editions in a decade, his reputation as one of Italy’s greatest climbers seemingly assured. And in each edition the caption to this last photograph of her brother, the one Stefanie is now looking at, remained the same: ‘Toni Egger on the lower slabs of Cerro Torre.’

For close students of Cerro Torre’s troubled history, this photograph has long prompted questions and a vague sense that something, somewhere, is not right, and for one simple reason: it shouldn’t exist. When Cesarino Fava, the third member of the Cerro Torre expedition, who only climbed low on the route and waited in camp while Egger and Maestri climbed on, discovered Maestri more dead than alive at the foot of the granite tower, the only evidence Maestri could offer that he and Toni Egger had reached the summit was his word and his story. The only camera with them had been lost with Egger in his fatal fall.

So where had this photograph come from?

Kelly Cordes, in his compelling history of Cerro Torre, The Tower, explains how Egger injured his foot approaching base camp, a wound that became infected, keeping the Austrian at base camp for the initial stages of the expedition. While Egger was recovering, Maestri, with Fava in support, fixed the first 300 metres of the route. Then, according to Maestri’s account, he and Egger left for the summit. So if Egger fell to his death on the descent, losing the only camera, how could Maestri publish a photograph of Egger on the lower slabs? The short answer is that the photo is of an entirely different mountain.

‘We [Patagonia experts] knew the photo wasn’t taken on Cerro Torre, as no place Maestri went there resembled the image,’ Cordes told me. ‘But it could have been anyplace – could have been back in the Alps, elsewhere in the Chaltén massif, who knows.’

Cordes knows that if you are looking for a needle in a haystack, then ask the man who knows the haystack best. When it comes to Cerro Torre and the Chaltén massif, that man is Rolando Garibotti. Born in Italy and raised in Bariloche in northern Patagonia, Garibotti did his first route in the Chaltén range at fifteen years of age. Not only did he write the guidebook to Patagonia, his book is widely regarded as a classic of its genre, underpinned by knowledge and research that is best characterised as relentless. In 2004, the American Alpine Journal, where Cordes was then working, published a seminal examination of Maestri’s claim titled ‘A Mountain...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 31.7.2017 |

|---|---|

| Vorwort | Katie Ives |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Anthologien |

| Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte | |

| Literatur ► Essays / Feuilleton | |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport | |

| Schlagworte | Alex MacIntyre • alpine climbing • Alpine Journal • Andy Kirkpatrick • Annapurna • Bernadette Mcdonald • Big Guts • Bonington • Cerro Torre • Cesare Maestri • Chris Bonington • climbing art • climbing articles • climbing book • controversies in climbing • crazy wisdom • Ed Douglas • Edward Douglas • famous climbers • Himalaya • Himalayan climbing • Himalayan mountaineering • Humar • ice climbing • Katie Ives • Kurt Albert • Langtang Lirung • Lines of Beauty • Lone Wolf • Magician's Glass • Marko Prezelj • Nepal • Nick Colton • Patrick Edlinger • rock climbing book • Searching for Humar • Stealing Toni Egger • Stefanie Egger • The Magician's Glass • Tomaz Humar • Tomo Cesen • Toni Egger • Ueli Steck • What's Eating Ueli Steck • who invented the redpoint |

| ISBN-10 | 1-911342-49-5 / 1911342495 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-911342-49-6 / 9781911342496 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 1,2 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich