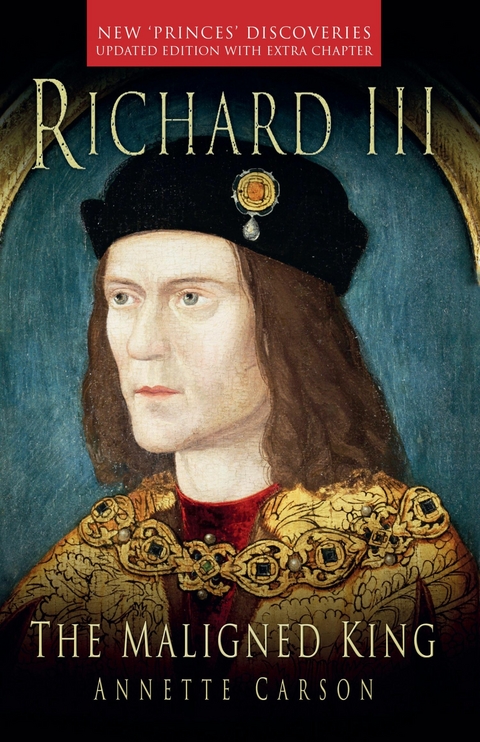

Richard III: The Maligned King (eBook)

352 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-0-7524-7314-7 (ISBN)

Annette Carson is a professional writer and has been an editor and award-winning copywriter. A prominent Ricardian, in 2011 she was invited by Philippa Langley to join the team searching for the king's lost grave, which found and exhumed Richard's remains for honourable reburial.

Preface

This book is not a biography of Richard III. It is a highly personal analysis of the more controversial events of that king’s reign, starting with the death of his predecessor and brother, Edward IV, in 1483.

At the outset my aim was to research, not to vindicate. However, in the course of my progress many surprising things became evident. Among them was the determination of most historians to place negative interpretations on Richard’s actions, while applauding the career of deceit and underhandedness that characterized his nemesis, Henry VII.

Thus, the thrust of my writing gravitated towards Richard’s defence. I do not claim to have found unequivocal answers; but I have delved as deeply as possible into particular topics that seem to need exposure to the clear light of day, seeking for a kernel of truth under layers of misinformation. Sometimes I offer conjectures, mine and other people’s, that disturb long-established comfort zones. I offer them in support of a truth too often overlooked: we do not know as much as we are led to think we know. Context is everything, especially with equivocal events – for example speculation around Edward IV’s death and its date. I see a clear parallel with the way theorists have interpreted historical records over the centuries to build their case against Richard III.

Although my main interests lie in the oft-ignored nooks and crannies of history, let me emphasize that this book is written for the ordinary reader – anyone who knows a little about King Richard III of England and would like to know more. A strand of narrative runs through it all which ensures that we keep following the story of Richard III’s reign as it unfolds.

Above all you will find none of the sweeping judgements so loved by historians (good, evil, prudent, ambitious, pious, hypocritical, etc.). Richard was a man of his times and a king of his times, concerned with matters beyond the experience of any twenty-first century commentator.

Current academic orthodoxy concedes that Richard III was probably not the monster of Tudor mythology, but assumes the rationale behind his seizure of the crown must have been a fiction; that being a usurper, he must have had his two nephews murdered because that was what usurpers did; and that their murder was, on balance, confirmed by the bones inurned in Westminster Abbey by Charles II. These are, inter alia, assumptions that I challenge in these pages.

Those who cast Richard III as an unprincipled usurper have done so because they have made judgements and drawn conclusions: no concrete evidence exists to convict him. But academic orthodoxy is a tough nut to crack, and is passed on to each new generation of scholars.

If Richard III is to be assessed, let it be on his overall conduct as a sovereign. When it comes to matters in which he had some control, such as legislation brought before Parliament, his record has been recognized over the centuries as significant and enlightened. By contrast with kings before and after him, he indulged in no financial extortion, no religious persecution, no violation of sanctuary, no burning at the stake, no killing of women, no torture or starvation and no cynical breach of promise, pardon or safe-conduct in order to entrap a subject. Anyone who has been led to believe that Sir Henry Wyatt was tortured by Richard III is recommended to read my comprehensive refutation of that myth (see www.richardiii.net/downloads/wyatt_questionable_legend.pdf ).

After Richard’s death the story of the murderous, tyrannical king was fostered by his killers and became part of English legend. Encouraged by a climate of Court approval, chroniclers vied with each other to heap venom on his memory and devise horror stories to add to his constantly growing list of crimes. In their ignorance they jeered at his physical form and heaped on him an assortment of grotesqueries, believing that an ill-formed body was the outward manifestation of an evil mind. This fictitious Richard III became the subject of one of Shakespeare’s most alluring melodramas. Shakespeare had little need for invention: he found the entire artifice already crafted to perfection by the Tudor chroniclers.

By contrast, the scant information dating from pre-Tudor times is generally found in letters and jottings, cursory government records, or a few isolated narratives. The unreliability of the latter is amply demonstrated in the works of John Rous, a Warwickshire priest who fancied himself a chronicler. Rous generously left to posterity two opposite views of Richard III: the first, composed during his reign, admiring and complimentary; the second, composed after his downfall, hostile and vituperative.

The example of Rous illustrates how important is familiarity with the source material when it comes to forming an independent opinion. Here, therefore, you will find an unusual approach: an Appendix is provided which contains a list of the principal sources used, together with notes about factors which may be relevant to the credibility of the writers. These include dates; partisanship; motivation; whether answerable to a patron; whether facts were accessed at first hand and, if at second hand, the reliability of the likely informants. The notes are mine, taking into account analyses by historians and academics.

In the last resort the issue of credibility is a matter for the individual to determine, and I cannot substitute my judgement for yours. Nor is it my intention to provide scholarly analyses of sources. As an author I have made choices as to which are reliable enough to be quoted in evidence, and which are, to a greater or lesser extent, dubious. If a source is so biased that it must, in my opinion, be read with inordinate care and circumspection, or if written by a person too far distant in time or location from the events he purports to describe, then it will be mentioned only if there is some exceptional reason for doing so – and then with a health warning attached.

I have taken as my main sources two narratives that were written by people who were present when most of the events they describe took place. The first is an intelligence report produced for his foreign master by an Italian cleric, Domenico Mancini, after visiting London in 1483. The second is also probably the work of a cleric, an anonymous Englishman this time, who in 1485–6 related his version of recent secular affairs while contributing to the ongoing Chronicle of the Abbey of Crowland; a man who seems to have enjoyed a degree of intimacy with the centres of political power. Even these sources are marred by identifiable errors and partisanship, but they are undoubtedly the best we have.

A third important writer, Polydore Vergil, produced a gigantic history of England in the early sixteenth century at Henry VII’s behest. Vergil’s treatment of Richard suffers from the same drawbacks, with a few new ones into the bargain: he writes at a distance of over two decades after the events; he is an Italian with no personal knowledge of Richard III’s England, so his material is gleaned through informants; plus he always has to keep an eye on the interests of his patron.

Nevertheless, Vergil made manful efforts to get factual information, both written and oral. Regrettably, commentators have given equal credence to writers of his century with far less claim to credibility, whose fantastic stories have been believed and retold in all seriousness. In this book the reader will find scant place for such works of imagination, into which category Thomas More’s History of King Richard the Third is firmly relegated.

Though written more than a generation after the event, and crafted as a literary piece with an underlaying didactic message, More’s apologue is still trusted and quoted by experts up to the present day. Unfortunately, because so much of popular tradition about Richard derives from More, it has not been possible to ignore him altogether. In this connection it is instructive to consider who might have been his informants (see Appendix).

Such evaluation of sources is at the heart of all scholarship, and routinely gives rise to disagreements among historians. Unsurprisingly, opinions are polarized as to the relative value of Thomas More’s imaginative ‘history’. At one end of the scale we have David Starkey of television fame, who places utter faith in it as the work of a reliable historian – give or take a few blunders – while at the other end is Alison Hanham, author of an illuminating survey of Richard’s early historians, who labels it a ‘satirical drama’. See also a seminal paper, ‘influential in the development of a critical trend’, by Arthur Kincaid, ‘The Dramatic Structure of Sir Thomas More’s History of King Richard III’, Studies in English Literature 1500–1900: Elizabethan and Jacobean Drama (Rice University, Houston, Texas), Vol. XII, No. 2, spring 1972, pp. 223–242, twice anthologized.

Of course, professional historians tend to see it as their own peculiar and especial prerogative to evaluate sources. Charles Ross, in his 1981 biography of Richard III, speaks for many of his colleagues when he denigrates ‘revisionists’ for picking and choosing which portions of sources they believe. ‘For example,’ he says in his Introduction, ‘Polydore Vergil, as a Tudor author corrupted by [Archbishop John] Morton, cannot be relied upon, and yet becomes an acceptable authority when he reports a general belief that the princes were still...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 13.4.2017 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Mittelalter | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Neuzeit (bis 1918) | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | British Monarch • British Royalty • King Richard III • Medieval • Plantagenet • Richard III • royalty • royalty, british monarch, british royalty, richard III, tower of london, medieval, wars of the roses, Plantagenet • royalty, british monarch, british royalty, richard III, tower of london, medieval, wars of the roses, Plantagenet, king richard iii, thomas more, shakespeare • Shakespeare • Thomas More • Tower of London • Wars of the Roses |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7524-7314-X / 075247314X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7524-7314-7 / 9780752473147 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 11,5 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich