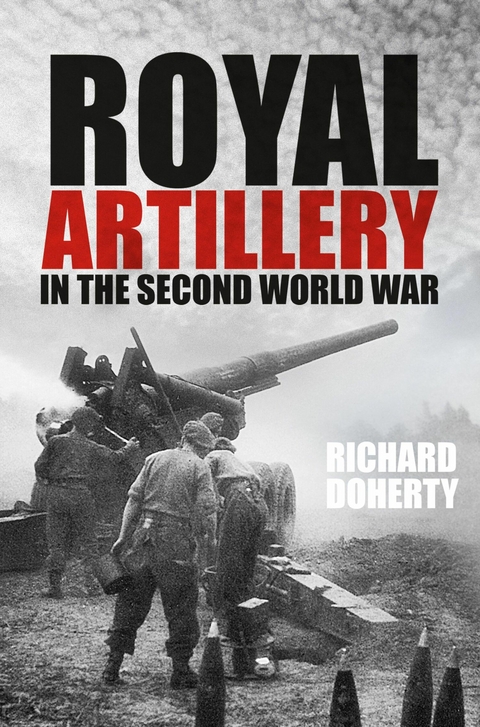

Royal Artillery in the Second World War (eBook)

320 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-0-7509-7931-3 (ISBN)

During the Second World War, the Germans considered the Royal Artillery to be the most professional arm of the British Army: British gunners were accurate, effective and efficient, and provided fire support for their armoured and infantry colleagues that was better than that in any other army. However, the Royal Artillery delivered much more than field and medium artillery battlefield support. Gunner regiments manned antitank guns on the front line and light anti-aircraft guns in divisional regiments to defend against air attack at home and abroad. The Royal Artillery also helped to protect convoys that brought essential supplies to Britain, and AA gunners had their finest hour when they destroyed the majority of the V-1 flying bombs launched against Britain from June 1944. Richard Doherty delves into the wide-ranging role of the Royal Artillery, examining its state of preparedness in 1939, the many developments that were introduced during the war including aerial observation and self-propelled artillery the growth of the regiment and its effectiveness in its many roles. Royal Artillery in the Second World War is a comprehensive account of a British Army regiment that played a vital role in the ensuing Allied victory.

Chapter One

Rumours of War

When the Great War ended the Royal Regiment of Artillery could reflect on having made a major contribution to Allied victory. Many lessons had been absorbed and gunnery had evolved greatly from the early days of war with the Gunners developing principles which survive to this day and which were put into effect during the Second World War. Not least of these was the principle of concentration of fire and speed in so doing, but there were others: there should be only one artillery commander at each level who must command all types of artillery allotted; gunner command and control must be linked directly to the tactical plan; operations without a fireplan are doomed to failure; artillery command must be well forward, and mobile. These were summarised by the late Sir Martin Farndale:

No other part of the Army can meet the severe demands of the principles of war as successfully as can the Gunners. Whether it be the persistent maintenance of the aim, day or night, in any weather or on any ground; the maintenance of morale by offensive action, which is the hallmark of all artillery operations; surprise – no Arm can produce surprise as can the Gunners; nothing is more surprising than the sudden, unexpected arrival of tons of high explosive on an unsuspecting target; no Arm can concentrate force as rapidly at one point on the battlefield, without the movement of its units, as can a divisional artillery correctly handled; a fundamental facet of the security of any position is an effective defensive fireplan; economy of effort cannot be better demonstrated, when needed, provided all guns are in range of the target; flexibility must be one of the most powerful characteristics of artillery, whether in method of attack, timing of attack or place of attack; no Arm relies so much on cooperation to achieve its aim. Alone it is effective but limited – with its comrades in the cavalry and infantry in full concert it is unbeatable; however, finally, without effective administration and, in particular, the provision of the weapon itself – the shell – it is useless.

But this is not all. Artillery command, control and communications must be second to none or all is lost. Battery commanders and forward observers without communications are useless. Guns out of contact with the battle are little more than mobile road blocks. In any operational plan the fireplan is paramount, for what is war but a gigantic fireplan? Artillery is flexible but is never unlinked to the main manoeuvre battle. It has never made, and must never make, the mistake of air-power which is totally flexible and, in the pursuit of flexibility, has disconnected itself from the operations of ground troops. Artillery must be kept clear of the manoeuvre battle but must remain an integral part of it.1

By 1919 the Royal Regiment was the world’s most professional artillery arm and faced the future with confidence. However, the 1920s became a decade of retrenchment as the Regiment reduced in size with the anti-aircraft element – built up so painstakingly in the late war – dismantled to leave but a single gun brigade2 and a searchlight battalion in the regular army; there were no AA units in the Territorial Army, re-formed in 1922, although the Territorial Force had provided a major element of the wartime strength of the artillery arm. Worse still, such had been the speed with which the War Office had run down the post-war Army that no evaluation of AA artillery, its tactics and the technical and logistic aspects of this field of gunnery had been made and thus no AA gunnery doctrine had been formulated while those with recent experience were still in service. Indeed, for six years there was no development at all in the field or, as Brigadier N W Routledge describes it, ‘there followed stagnation in the state of the art’.3

Unfortunately, this set the pattern for the inter-war years. The Army had to make do with what it had as the Treasury imposed the ‘ten-year rule’ which decreed that there would be no war in Europe for at least ten years. While this might have been fine had the rule been applied as a ‘one-off’ in 1919, it became a Treasury principle with a rolling ‘ten-year rule’ ensuring that the services remained short of funds until almost too late. Not until 1932 did the Cabinet abandon this rule. In the light of the history of the United Kingdom in the Second World War, it is worth noting that one of those who first promulgated the rule ‘that the British Empire will not be engaged in any great war during the next ten years, and that no expeditionary force is required for this purpose’, held the portfolios of War and Air. He was Winston S Churchill who, as Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1925 continued upholding the rule and used it to oppose plans to upgrade the Singapore naval base. In 1928 Churchill recommended that the rule ‘should now be laid down as a standing assumption that at any given date there will be no major war for ten years from that date’.4

Fortunately common sense prevailed in 1932. The rule was abandoned and investment began trickling into the services but there were many demands from all three services which could not be met immediately. Some investment in the Royal Regiment ensured that the bulk of the field artillery would be mechanised by 1939. New equipment was also funded, including that classic of field pieces, the 25-pounder, and the finest AA gun of the war, the 3.7. Since the size, diversity and range of roles of the Regiment meant that it sought a very large slice of the money available to the Army, it is appropriate to review the contemporary organisation of the Royal Artillery.

The division into Royal Field Artillery and Royal Garrison Artillery had been abandoned in 1924. (As if to add confusion, the Royal Horse Artillery was the corps d’elite of the Royal Field Artillery while the Honourable Artillery Company, a TA unit, also belongs to the regimental family.) However, it was decided that, once again, the Regiment should be split into two branches: Field Army and Coast Defence and Anti-Aircraft. The former included units designated as field brigades – later regiments – as well as medium, mountain and anti-tank units plus 1st Heavy Brigade, a survey company and section, and both mountain and medium units of the Hong Kong and Singapore Royal Artillery (HKSRA) while the latter took responsibility for coast defence and AA artillery, all heavy brigades and batteries other than 1st Heavy Brigade, home fixed defences and fire commands, and the AA and coast defence elements of the HKSRA. The paired functions of coast defence and AA were further divided into twin elements. Coast artillery included close defence guns and counter-bombardment guns with the former using automatic sights that measured and set target ranges while the latter carried out longer range tasks. In the AA role there were heavy and light guns, the former deploying against high-flying targets and the latter against low-flying aircraft. (Searchlights, a Royal Engineer responsibility before the war, would be transferred to the Royal Artillery.) To complicate matters further, light AA units would also be assigned to the Field Army, initially at corps and later at divisional level. This re-organisation took effect in 1938, the creation of the Coast Defence and Anti-Aircraft branch having received Royal approval on 30 March.5

Also in 1938 a re-organisation of artillery units saw the lieutenant colonel’s command redesignated from brigade to regiment.6 The most important fire unit continued to be the battery to which, of course, Gunners owe their first loyalty. However, the new organisation established a field regiment of two twelve-gun batteries whereas field brigades had had four six-gun batteries. In regular regiments this led to a pairing of batteries so as to maintain the traditions of every battery: thus, for example, 19th Field Brigade’s 29, 39, 96 and 97 Batteries became 19th Field Regiment’s 29/39 and 96/97 Batteries.7 Royal Horse Artillery units were also re-organised; the three RHA brigades became 1st, 2nd and 3rd Regiments RHA but since the original brigades had included three six-gun batteries, the new organisation was achieved by withdrawing E Battery from India – linked with A Battery it joined 1st Regiment – and redesignating two onetime RHA batteries, H (Ramsay’s Troop) and P (The Dragon Troop), which had been in 8th Field Regiment and 21st Anti-Tank Regiment respectively. In the RHA, batteries were divided into two six-gun troops, thus allowing the troop to maintain the identity of the battery it had formerly been. A proposal that the twelve-gun unit should be styled a ‘battalion’ with the term ‘battery’ retained for the six-gun unit came to nothing.8

For the Territorial Army the effect was not so traumatic as re-organisation coincided with the decision to double the TA. Thus each TA field regiment could throw off two batteries to form a duplicate unit; 60th (North Midland) Field Regiment’s second and fourth batteries – 238 and 240 – became 115th Field Regiment RA (North Midland) (TA), a pattern repeated across the TA throughout Great Britain.9 Medium, heavy, coast and anti-aircraft regiments did not suffer to the same extent as field units, apart from some pairing of regular medium batteries.

Field batteries were now divided into three troops, each of four guns, with command posts at both battery and troop. A battery command post was manned by the command post officer (CPO) with the necessary assistants, telephonists and radio-operators, a...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 22.7.2016 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Natur / Technik ► Fahrzeuge / Flugzeuge / Schiffe ► Militärfahrzeuge / -flugzeuge / -schiffe |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Neuzeit (bis 1918) | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► 1918 bis 1945 | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Militärgeschichte | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| Schlagworte | aerial observation • alamein line • anti tank • Battle of El Alamein • british gunners • dunkirk campaign • eight arym • operation lightfoot • Ra • Regiments • Royal Artillery • Second World War • sel-propelled artillery • Unique • World War II • World War Two |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7509-7931-3 / 0750979313 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7509-7931-3 / 9780750979313 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 15,1 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich