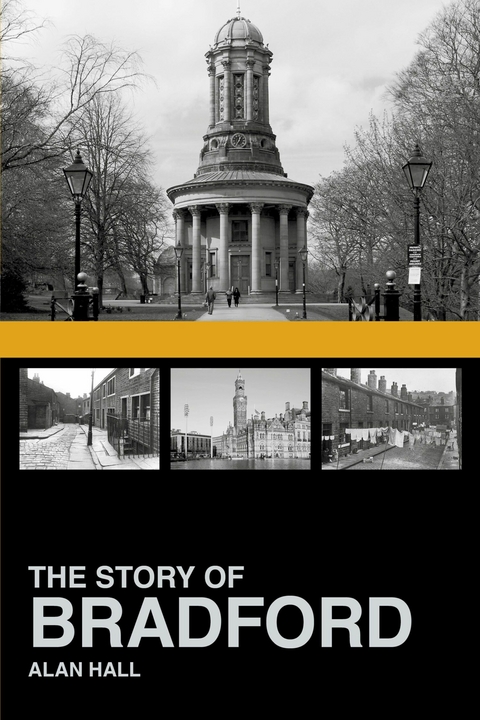

Story of Bradford (eBook)

224 Seiten

The History Press (Verlag)

978-0-7509-5236-1 (ISBN)

Alan Hall is a historian and author. He live in Shipley, West Yorkshire, and is vice chair of Bradford Civic Society.

The Story of Bradford traces the city's history from earliest times to the present, concluding with comments on the issues, challenges and opportunities that the 21st century will present. The departure of the German wool merchants in 1914 and the tragedy that befell the Bradford Pals at the Somme had a serious effect not just on the city but further afield, while the achievements of the great nineteenth-century wool barons are contrasted with the condition of the working-class and industrial unrest. The challenge in the new millennium is for Bradford to use its considerable assets - including the architectural development and heritage - to shine as a prosperous and self-confident community.

one

EARLY TIMES

Until the early years of the twenty-first century, just across the River Aire from Saltaire, was a public house with a curious name, the Cup and Ring. The name has nothing to do with drinking vessels or boxing matches; rather it alludes to a collection of boulders with strange markings that can be found a couple of miles away at the edge of Baildon Moor, quite near to Baildon Golf Club. Nobody has offered a completely satisfactory explanation of what these stones signify, nor how long they have been there, although the consensus is that they probably date from the early Bronze Age and possibly had a religious significance. Such cup and ring stones are not unique to the Bradford area; they can be found in other places in the North of England and also in parts of Scotland. Baildon Moor also contains several burial mounds from the Bronze Age, and some axes believed to be from this period have been found in the locality. Flint arrow-heads, probably from an earlier period, have also been found on Baildon Moor and in other parts of Bradford, notably Thornton, West Bowling and Eccleshill.

Celtic tribes migrated from mainland Europe to Britain from about 500 BC onwards, and these were the people that the Romans encountered when they began to colonise the country after AD 43. With the exception of the so-called swastika stone on Ilkley Moor, another boulder with unexplained markings but believed to be of Celtic origin, there is scant evidence of a Celtic presence in the Bradford area. Roman coins from the first and the fourth century AD have, however, been found in various places throughout Bradford, including Heaton, Idle and Cottingley, indicating the possibility that local Celtic people traded with the Roman occupiers, or used the coins for commercial activities between themselves.

It has to be said that these archaeological finds, especially when compared with what has been unearthed in other parts of Britain, do not amount to very much. This would seem to show that Bradford and its environs were rather off the beaten track. There was a Roman fort at Ilkley – called Olicana – but it was relatively small, and its prime function was to safeguard communications across the Pennines and keep the local population under control. There is no evidence that any Romans ever set foot in the bowl-shaped valley that was to become the centre of the city of Bradford; there was no real reason for them to do so. They may have had dealings with the primitive iron industry that existed at Bierley, as Roman coins have been found at this site, but this does not necessarily mean that any Romans actually visited the place.

Celtic people in the area would almost certainly be members of the Brigantes tribe who inhabited a large part of the North of England and were never completely subjugated by the Romans. We do not know to what extent, if any, local people were involved when the Brigantes revolted against the Romans in the first and third centuries AD. In short, with the exception of Olicana, the Roman occupation of Britain largely passed the Bradford area by.

Bronze Age Cup and Ring stones, Baildon Moor. (Sue Naylor)

Angles and Scandinavians

The Romans left Britain in the early part of the fifth century AD and between then and the Norman Conquest the country was subjected to successive waves of immigrants from what is now Germany and Scandinavia. Older histories often took the line that the Celtic inhabitants of Britain were forced westwards en masse into Wales and Cornwall by these incoming peoples; modern historians tend to believe that, while there were episodes of conflict, such as the Battle of Catterick in AD 600, in the longer term the newcomers and the Celts probably intermarried, and the reason that the western extremities of Britain remained predominantly Celtic was simply because the Anglo-Saxons never settled those areas in any numbers. The particular people who settled in what was to become West Yorkshire were the Angles, who are believed to have migrated from what is now Schleswig-Holstein in northern Germany. It is likely that they assimilated the Celts rather than driving them away. And the same process was probably repeated when the Norse people, or Vikings, arrived in the area in the ninth and tenth centuries.

The barbaric and bloodthirsty reputation of the Vikings owes much to their portrayal in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which was written by Christian monks who naturally felt antagonistic towards the pagan Norsemen. In fact the Vikings established a flourishing independent territory – the Danelaw – in the North of England, with its capital at Jorvik (York). They eventually converted to Christianity and, once established on the land, were unlikely to have been particularly hostile to their Angle neighbours. Their hostility was more likely to have been directed towards the Saxons of southern England who constantly sought to dominate them and take away their independence, right up to the time of the Norman Conquest. Viewed in this light, Alfred the Great, King of Wessex, is not so much a national hero for people in the North of England, but rather an oppressor of their forebears.

Again, archaeological remains from this whole period are very few in the Bradford area, but at least it is possible to tell something about how the land was settled by a study of local place names. Thus the Anglo-Saxon ending -ton, as in Thornton, Clayton and Allerton, indicates an enclosure, while the very common ending -ley, as in Keighley and Bingley, indicates a clearing in woodland. It is easy to deduce from this that Skipton originally meant an enclosure for sheep and Shipley meant a clearing for sheep. There is evidence of Norse settlements too in place names like Micklethwaite, near Bingley. Denholme may indicate a Danish settlement, although den is also the Anglo-Saxon word for a small valley (modern English dean or dene). Bradford itself derives its name from the words for broad and ford and refers to a settlement that was established at a crossing point on a tributary of the River Aire. The ford was almost certainly in the vicinity of today’s Forster Square.

Angle and Scandinavian influences can also be seen right up to the present in the way many people from West Yorkshire speak. Local people typically use short vowels and a rather flat intonation, making their speech sound quite different from that of southern England, which was mainly populated by the Saxons. Southern English had much less linguistic input from Scandinavia. Many words that have their origins in Denmark and Norway are still in common use in West Yorkshire. Instead of hill-walking local people will walk the fells and dales (valleys), perhaps stopping to cool their feet not in a stream but a beck, before refreshing themselves with some ale while watching their barns (children) laiking (playing) or ligging (lying down) on the grass to rest. Even ta, often wrongly dismissed as a slang or infantile word, is cognate with the modern Danish word tak, which is the word for thanks.

The Norman Conquest

The people of the North of England did not readily accept England’s new Norman rulers after the Conquest of 1066. Three years later there was an uprising, which King William crushed by laying waste large areas of land north of the Humber. This was the so-called Harrying of the North. The entry in the Domesday Book of 1086 shows that the manor of Bradford was itself laid waste: ‘In Bradeford with six berewicks, Gamel had fifteen caracutes of land to be taxed, where there may be eight ploughs. Ilbert has it and it is waste. Value in King Edward’s time four pounds.’ In more modern parlance this means that in the manor of Bradford there were eight ploughs belonging to the lord of the manor to cultivate about 1,600 acres, and that the local lord in Edward the Confessor’s reign was called Gamel. We know from the Domesday survey that Gamel also held land at Gomersal and Mirfield to the south of Bradford. We know very little else about him, but most, if not all, of his lands were given to a Norman called Ilbert de Lacy, as a reward for helping William in his successful campaign of conquest. Other manors that were much later to become suburbs of Bradford, or towns and villages within the Bradford Metropolitan District, are likewise described as waste; most of them were also taken over by Ilbert de Lacey.

Ilbert held a considerable amount of land in Yorkshire (and beyond) as a tenant of the king. Under the feudal system he would have been able to derive an income from his various manors in terms of rents and agricultural produce and, in return for being granted his lands, he was expected to be totally loyal to the king and provide money and military levies when required. As the North was still in need of firm control, Ilbert built strongholds throughout his domain, the most important being Pontefract Castle. When the de Lacey line died out in the early fourteenth century the manor of Bradford became part of the Duchy of Lancaster. By then the king had granted permission for a weekly market (1251) and an annual fair (1294) to be held in the town. The first mention of a parish church also dates from this time, and Bradford may have been developing into something of a local centre, although Bingley (1212) had a market granted by the king earlier than Bradford.

Bronze Age Swastika stone, Ilkey Moor. (Sue Naylor)

It has been estimated that Bradford had a population of about 650 in 1311, twice the number reckoned to be dwelling there at the time of the Conquest. But the population fell back to about 300 by 1379, probably because of a series...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.7.2013 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik ► Regional- / Landesgeschichte |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie ► Lebenshilfe / Lebensführung | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | archive photographs • Bradford • bradford book • bradford gift • bradford history • bradford pals • city of culture 2025 • german wool merchants • local bradford • Post-industrial • West Yorkshire |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7509-5236-9 / 0750952369 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7509-5236-1 / 9780750952361 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 57,0 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich