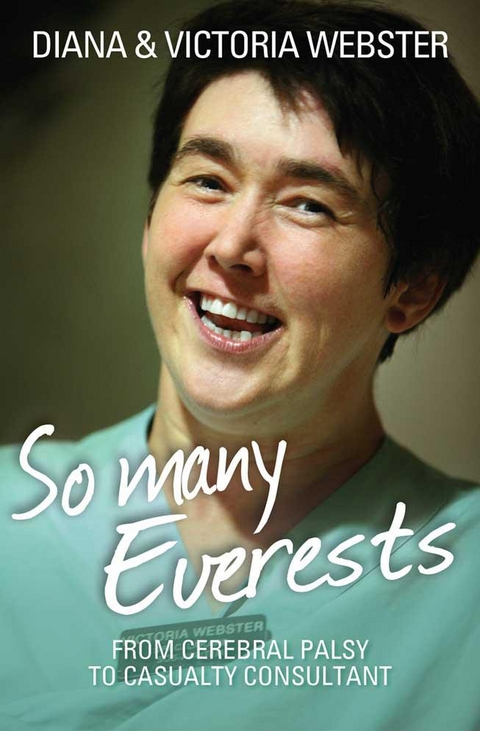

So Many Everests (eBook)

240 Seiten

Lion Hudson (Verlag)

978-0-7459-5761-6 (ISBN)

Victoria Webster was born with cerebral palsy and that meant, for many of those involved in her education, that she should limit her horizons. But Victoria had her eyes, and her heart, set on a high peak of achievement to be a doctor. And, despite everything she tackled taking her longer than most of her peers, despite assurances that her patients would object, despite suggestions that she give up, she persevered and became not only a Casualty Consultant but the first Casualty Consultant in Sweden. Surrounded by loving family from her birth onwards, Victoria's story is also her mother's, Diana's story, and together they tell of the mountains scaled and conquered. This is wonderful, heart-warming and encouraging read. 'This is easily the most moving book I have read.' Katherine Whitehorn, journalist and columnist

CHAPTER 2

I dozed fitfully in my bed in the maternity ward until the morning began to grey. They had put me in a separate room, so again I was alone. Sometimes I was wakened by the distant cry of a baby. Not mine, though.

Finally the events of the night began to return and I woke up for good. I felt strangely detached, as if I had never had a baby, but my fingertips still remembered a warm, silky skin. They had taken it away to give it more oxygen, they had said. Surely oxygen was something essential? What did a lack of oxygen mean? Would it damage the baby and, if so, how? Where was Mike? I wanted Mike.

‘When can I see my husband?’

The nurse spoke some English. ‘In visiting hours, Mrs Webster.’

‘When’s that?’

‘Between one and two o’clock.’

‘But that’s another six hours away! Can’t I see him before that?’

‘I am sorry, no, Mrs Webster. They are the rules.’

‘Can I telephone him then?’

‘Yes, of course. I will bring a telephone to your room.’

The phone didn’t come. Gingerly, I got up – the birth had torn me and I had had to have several stitches, so sitting down had to be done carefully, balancing on the side of one buttock. I went out into a white corridor and walked along to find a nurse or a phone. As I did, I passed a long glass window in the left-hand wall. I looked through. Babies. Rows of baby faces peeking out of swaddling bands in their cots like tiny Egyptian mummies. Some I could see were crying, crumpling up the folds of their faces and opening and shutting their mouths, some squidging a grimace, some giving a delicate little yawn, others sleeping tranquilly. Some had tufts of black hair showing, some had a faint yellow down, some were totally bald. None of them was my baby. I returned to my room.

After a long, long while someone came with a telephone. I dialled our number, but Mike wasn’t at home.

Suddenly I felt impelled to do something, anything that might help the baby. So far I had been, it seemed, totally helpless, a mere birth-machine in the hands of others who had decided everything for me and had finally removed my baby. That baby was somewhere here, though, in this very hospital, in an oxygen tent. Was she still alive?

Then I remembered Pelle. Pelle was a consultant at one of the children’s hospitals in Helsinki and was a friend of my mother’s – wouldn’t a special hospital be better than here? In any event, there would be someone who knew us at the other hospital, to whom the baby would not just be any baby but our baby.

It was a Saturday and I prayed that he would be there, knowing that doctors often did not work at weekends, but Pelle was on duty. He was always a laconic man and no more so than on the telephone. He just listened and said: ‘Right. I’ll get her over here right away.’

He didn’t offer comment or sympathy – he just acted – and I lay back on my bed with a huge sense of relief. She’d be all right now – Pelle would see to it.

I waited through the long, long time until visiting hours. At last Mike opened the door and came over to hug me.

‘I’m so sorry, sweetie,’ he said.

‘You know?’

He nodded. ‘They phoned me.’

‘They gave her four points at birth, they said.’

‘What does that mean?’

‘Apparently they give points to babies when they are born. As if they were in a health race. Ten points to the best babies.’

‘Ah.’ We looked at each other.

I said: ‘I got through to Pelle. He said he would get her sent over straight away to the Children’s Hospital and look after her.’

‘I know. He told me and I went over to see her.’

‘You’ve seen her?’

‘Such a pretty baby, sweetie. Lots of black hair.’

‘I couldn’t really see. She was almost all covered up when they showed her to me.’

‘A lovely baby. Clever old you.’

It was much, much later that Mike told me that when he saw her in the Intensive Care Unit she was having a convulsion. She was in a domed glass case, like a Victorian trophy, with a tube in her nose; while he was there she turned rigid, blue. He never said either then or later what his feelings were about the whole thing but just did everything he could to make me feel better.

‘Look, I’ve brought you this.’

He held up an unsightly dark red rubber ring, which he proceeded to blow up.

‘What…?’ I said.

‘It’s for people with piles, but I thought it would do for you.’

I giggled and tried sitting on it. From then on, for my three or four days in hospital I was the envy of many a precariously buttock-balancing mum. I asked a nurse if it wouldn’t be a good idea to have a supply that women could borrow.

She shook her head disapprovingly. ‘No, it is not good for mothers,’ she said.

‘Why on earth not?’

‘They heal better with no… no cushion.’

I didn’t believe her for a moment – ‘They just haven’t thought of it,’ I said to myself, and continued to sit comfortably. There seemed in fact to be a general feeling in Finnish hospitals at that time that pain was essential to childbirth, perhaps because of the famous Finnish sisu, a word which expresses a kind of stoical persistence in the face of all hardships. An Italian friend of mine, who had a baby a couple of years later in a private hospital, asked as I had for something to help the pain, but was told curtly and unsympathetically: ‘You can’t expect to have a baby without pain. Finnish women don’t.’

Attitudes have fortunately changed since then and Finland is as advanced as any other western country in pain relief. Changes have happened elsewhere too: husbands are regularly present at the actual birth and there would be no rules about visiting hours for a husband to visit a wife whose baby had been taken to intensive care or who had died. But it was not so in 1965 – and worse was to come.

A couple of days later I woke up to a soaking wet nightie and sheets. I couldn’t think at first what had happened. There was a familiar and yet unfamiliar smell, slightly sour. Milk? Yes, but… Again the books hadn’t mentioned this aspect of it – I didn’t know you leaked. There had only been pictures of a happy mother and a blissfully sucking baby. I hadn’t realized either that you could have milk without having the baby. It seemed so unfair.

When the nurse finally came, she said: ‘Ah, your milk is in, Mrs Webster. I bring a bowl.’

A bowl? What would I do with a bowl? Have the milk with cornflakes?

The nurse came back with a largish metal bowl.

‘Here you are,’ she said. ‘You must – express – the milk.’

‘Express?’ I asked, baffled.

She made movements of pulling at her own nipple. I realized that she meant I must milk myself. Like a cow, I thought. After all, that’s what happened to cows, wasn’t it: they had a calf, then the milk came for the calf, then the calf was taken away but they kept on milking the cow. I suppose they leak too if they aren’t milked. Poor bloody cows.

‘I show you,’ said the nurse. ‘It is easy.’

She put her finger and her thumb on either side of my nipple with a squeezing motion and a spray of milk shot out into the bowl.

‘Now you try.’

It had looked easy. However, it was surprisingly difficult to master, to find exactly where to press, the precise movement of the fingers needed and the critical pressure. After I had tried and failed several times, the nurse said: ‘I get you – machine.’

She returned with a metal instrument with a small cup which she clamped to my breast. The milk began to come out again. I remembered those rows of cows in the milking sheds with metal pumps attached to their teats. No, I would not be a dairy cow.

‘Stop, please,’ I said. ‘I want to try again myself.’

And finally I did get the hang of it. A steady stream of milk squirted in a narrow spray against the side of the metal bowl. I recalled the sound. As a child on a farm in the summers in England I had watched the farmhand milking a cow by hand: siss! siss! siss! into the metal bucket. I also remembered a painting I had seen of a Madonna and Baby, one of the thousands, by – whom? some Italian? – but the only one I had ever seen where the milk was coming out of Mary’s breast in a fine spray of misty white. Well, at least that artist had seen the real thing and recorded it, although I did not feel a bit Madonna-ish.

‘Why do I have to do it?’ I asked the nurse. ‘What’s the point when I haven’t got a baby?’

‘Then you make more milk. It do not stop. So then when Baby come home, you can feed her.’

‘Oh yes!’ I said eagerly. ‘I want to do that.’

‘And before baby is well, you can take your milk to hospital each day.’

‘But would she get it?’ I asked. ‘Would it go to her?’

‘Oh yes,’...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 19.10.2012 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Natur / Technik | |

| Medizin / Pharmazie ► Medizinische Fachgebiete ► Notfallmedizin | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7459-5761-7 / 0745957617 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7459-5761-6 / 9780745957616 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich