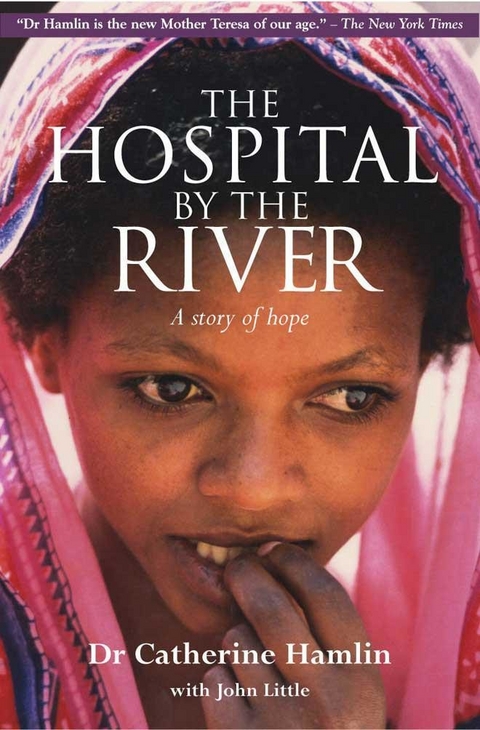

Hospital by the river (eBook)

320 Seiten

Lion Hudson (Verlag)

978-0-85721-407-2 (ISBN)

Gynaecologists Catherine and Reg Hamlin left Australia in 1959 on a short contract to establish a midwifery school in Ethiopia. Over 40 years later, Catherine is still there, running one of the most outstanding medical programmes in the world.

Chapter Two

I am sometimes asked how I have come to spend the greater part of my life in Ethiopia. The answer is simple. I believe that Reg and I were guided here by God. It is not inconceivable that the call was uttered long ago, before either of us were born. There is a verse in the Psalms which says, ‘For you have heard my vows, O God; you have given me the heritage of those who fear your name.’ Both Reg’s family and mine have a tradition of missionary service dating back at least to the nineteenth century. It is quite possible that one or another of our ancestors might have prayed for their work to continue with future generations.

My great-grandfather, Henry Young, was born at Masulipatam (now better-known as Machilipatnam), India, in 1803. As a young man he worked for the Honourable East India Company. He was a keen scholar, so gifted that he rapidly gained promotion until he became the youngest judge in India.

Although he seemed set for a brilliant career, he heard a more compelling call. He gave it all up to travel with his wife, Catherine, to England to preach the gospel. Having resigned his post, he thought it would be wrong to accept the large pension to which he was entitled. His daughter, Florence, wrote in her autobiography Pearls from the Pacific, that she ‘often heard him speak of the joy of this ministry and of the blessedness of entire dependence on God for the supply of daily needs’.

Despite these sentiments, in 1860 the necessity to support his family brought him to New Zealand, and he began farming near Invercargill in the South Island. The family struggled to make a living from the land. Rabbits were in plague proportions, and they had to wage a constant battle against weeds, thistles and other pests.

Catherine was by all accounts a frail woman, constantly beset by ill health. In the exceptionally cold winter of 1875 she and one of her sons, Horace, contracted pneumonia. At eight o’clock one evening the doctor was called. He informed the family that Catherine was too frail to fight the disease and would probably not live through the night. Two hours later she passed away. Horace, however, survived.

Horace was my grandfather.

Three years later Henry Young decided to sell up and move to Australia. He bought property near Bundaberg in Queensland, which he named Fairymead. Among the children who went with him were Horace and Florence. With the help of a labour force of Kanakas from the Solomon Islands and the New Hebrides, they commenced cultivating the land and building a mill for a sugar plantation. While this pioneering work was going on Horace married Ellen Thorne, whose family was originally from Tasmania. They were to have three sons and five daughters. One daughter, Elinor, was my mother.

When Florence, my great-aunt, got to know some of the Pacific Islanders, whom she described as ‘Merry, warm-hearted and very responsive to kindness,’ she was appalled that they had never heard of Jesus Christ. She decided to try to remedy the situation, beginning with a Sunday class in an old wooden humpy, attended by ten stalwart men and the housegirl. With the help of coloured pictures, she taught them about Creation and the death and resurrection of Jesus.

By the time the first harvest was in, in 1885, the classes had increased to 40 and by the following year there was an average attendance of 80 people on Sundays and 40 every evening. She must have had tremendous energy. By 1887 she had founded the Queensland Kanaka Mission, administering to 10,000 Islanders.

Florence writes that in 1890 she turned her attention to the ‘unreached heathen’ in China. Although the Chinese were reluctant to embrace Christianity, she persevered for ten years, rejoicing in the occasional convert, until the Boxer Rebellion forced her to quit the country and return to Brisbane.

Shortly after she came home, in October 1900, the Australian Government passed the Pacific Island Labourers Act, sending all Kanakas back to where they had come from. The thought of these people being cast adrift in a pagan land weighed heavily on Florence, and in March 1904 she and a companion, Mrs Fricke, and three male missionaries, left Sydney bound for the Solomon Islands. They found the Islanders split into two fiercely divided groups – the saltwater people, who lived on the coast, and the bush people, who lived deep in the almost impenetrable bush of the interior. The bush people were in a state of constant war with one another. Men, women and children were shot, speared or clubbed in endless vendettas. Missionaries and Islanders who had converted were regarded with suspicion and hatred.

Undaunted by these obstacles, Florence began spreading the gospel, journeying back and forth from Queensland to the Solomons for the next twenty years – often laid low by fever, encountering setbacks and hostility, but never giving up.

She lived to the age of 84. I cannot remember meeting her, but my two sisters, Sheila and Ailsa, have faint recollections of visiting a rather formidable old lady in retirement at Killara in Sydney, where she still occasionally taught Sunday school.

I do have clear memories of my grandmother, Ellen. When she and Horace retired, they left the heat of Queensland and built a grand house, Silvermere, at Wentworth Falls in the Blue Mountains near Sydney. They had been there only a year or so when Horace died. Granny kept the big house on. Our family used to visit her every Boxing Day with all her other grandchildren. We spent many happy holidays with her.

After rising early and starting the day with a cold bath, Granny would shepherd us together for prayers then accompany us on the harmonium while we sang hymns. The servants were expected to take part as well.

With an aunt like Florence and a mother like Ellen, it is little wonder that my mother, Elinor, had strict Christian values and a vibrant faith, which she passed on to all her children.

My father’s father, James Nicholson, was born at Stirling in Scotland on 10 March 1863. He became a partner in the London engineering firm of Richard Waygood and Co. In 1891 he was sent to Australia to sort out some management problems in the Melbourne office and ended up taking over the branch in exchange for his London partnership.

After marrying my grandmother, Ethel Beath, Grandfather moved to Sydney. His company merged with another to become Standard-Waygood Ltd. They became renowned as lift manufacturers. Grandfather had a flair for business. He made a great deal of money and gave much of it away, living without ostentation. ‘I try to lay up treasure in heaven,’ he would say, ‘rather than on earth.’

Most of his philanthropy was anonymous. He was deeply interested in missions and missionary work, and so was my grandmother. Three of her sisters were missionaries and three of their descendants also became missionaries.

Grandfather was a great supporter of the Sudan Interior Mission with which, coincidentally, I had dealings myself decades later. When the Italians invaded Ethiopia in 1935, the SIM in Addis Ababa decided they would either have to leave Africa altogether or re-establish in Khartoum. One of the missionaries, Mr Cain, wrote to my grandfather asking for funds to make the move. For weeks they waited without receiving a reply. After praying about this they resolved that if the money hadn’t come in a fortnight’s time, they would pull out and go back to Australia.

On the final day a parcel arrived. As they unwrapped it their spirits rose and then plummeted again as they saw what it contained. It was a week-old Sydney Morning Herald. Despondently, one of the missionaries opened the paper and out fell a cheque for the exact amount they required. Suspecting that it could have been opened at the post office and stolen, Grandfather had hidden the cheque inside the rolled-up newspaper.

Grandfather had four daughters and two sons. His daughters all remained single – because, it was jokingly said, their father didn’t want them to marry unsuitable people. During the war Mary worked with the Sands homes for soldiers in Northern Ireland; these were recreation centres where soldiers on leave could relax and have contact with a Christian ministry. Elaine worked with the poor in the London slums. Constance went to China as a missionary, while Hope stayed at home and looked after her parents into their old age. Of the two sons, Jack, the younger, went onto the land in New South Wales. Theodore took over management of Grandfather’s business.

Theo was my father.

The Youngs used to come to Sydney each year from Bundaberg to escape the heat of the Queensland summer. Through their mutual interest in Christianity they met the Nicholsons, and the two families became friendly. Naturally, Elinor and Theo saw a lot of each other, but it wasn’t until the families went on a skiing holiday together in Europe that their friendship began to develop into something deeper. The first hint of interest on my father’s part came in Switzerland, when he asked Elinor to sew a button onto his shirt. She thought it was an odd request when any one of his sisters could have done it.

My mother was seventeen and my father was nineteen on that holiday. Their friendship slowly blossomed into a romance. When Theo visited Elinor he would always take her a bunch of violets, knowing that they were her favourite flower.

Theo proposed when Mother was 23; the pair were on a picnic together. She did not doubt that she was in love but there were complications. Inspired by her mother and her aunt, Florence, she had long had...

| Sprache | englisch |

|---|---|

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik | |

| Medizin / Pharmazie ► Gesundheitsfachberufe ► Hebamme / Entbindungspfleger | |

| Medizin / Pharmazie ► Gesundheitswesen | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie ► Mikrosoziologie | |

| ISBN-10 | 0-85721-407-1 / 0857214071 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-85721-407-2 / 9780857214072 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich