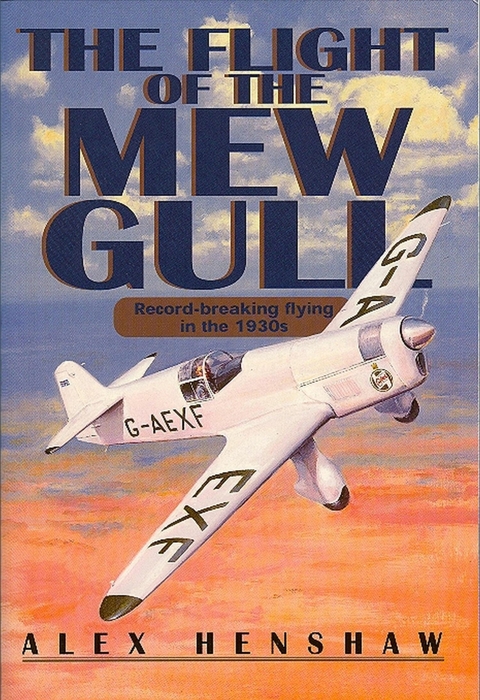

Flight Of The Mew Gull (eBook)

272 Seiten

Airlife (Verlag)

978-1-84797-408-2 (ISBN)

Awarded Siddeley Trophy 1933. Parachuted from blazing aircraft 1935. Crashed into Irish Sea 1935 King's Cup race. Won 1938 King's Cup race at fastest speed ever recorded. Broke all records to Cape Town and back 1939 which remain unbroken today. Awarded Brittania Trophy 1940. Chief Test Pilot Castle Bromwich factory 1940. Awarded MBE 1944. Queen's Award for Bravery 1953. HRH Duke of Edinburgh awarded Gold Medallion for contribution made to youth of this country 1997.

I must have caused my parents a great deal of worry. The earliest recollection I have of shock was on my mother’s face when a policeman came to the door with a summons for Alexander Adolphus Dumfries Henshaw. I think I was nine at the time. I was petrified and immediately thought of my poaching efforts on the railway cutting with my double-barrelled .410, but from the injured and ashamed look on my mother’s face, I guessed it must be something more serious. I had forgotten that two weeks before I had cycled to the cinema in Lincoln, and when I came to ride home in the dark, my lights failed. As it was five miles or more, I couldn’t walk, so I took a chance. Unfortunately for me, just when I thought I was in the clear an enormous figure loomed out of the night and grabbed my handlebars, and although I explained to the policeman that my dynamo had failed, he said I ought to know better and wrote things down in a little book. I now looked at this very official document with my name in clear print and wondered what my father would say. In fact he said very little, although he was not at all pleased. ‘You want to learn the eleventh commandment,’ he said. ‘It’s one of my own: Thou shall not get caught.’

I suffered days of anguish whilst my parents discussed who was to take me to court. Then quite suddenly the position came to me very clearly: no one was going to take me; I had got myself into this mess and I would get myself out of it. My mother would not hear of it, but my father, who I think really appreciated my stand, said ‘OK, if that’s how you feel about it.’ I knew the ancient Roman Stonebow very well, but I had not known it was also a Magistrates Court. I sneaked in and hid behind a chair.

Then suddenly huge lumbering policemen seemed to be everywhere and they were calling ‘Henshaw, Henshaw’. When I moved out of my hiding place, a policeman nearly fell over me and said, ‘What are you doing there, sonny? This is no place for you.’ ‘My name is Henshaw,’ I said. The magistrates were somewhat nonplussed and in reply to their query as to who was defending me, I said I didn’t understand what they meant. Then one of the elderly gentlemen on the bench asked me if I had any money. When I said I hadn’t, he asked, with a loud guffaw, if I knew the prison sentence for non-payment of fines. Before I could reply, a lady magistrate spoke up sharply and rebuked him for frightening the child. There was a hushed conversation between the Chairman, the Clerk, the policeman who booked me and a senior police officer. I guessed the police were getting it in the neck for having brought me there, as the constable, to my glee, back-tracked from the bench, very red in the face, and the lady magistrate said in a very kindly voice, ‘If you promise never to do it again, you can go.’

A few years later my mother looked out the window, exclaimed and said, ‘There’s a policeman coming up the drive!’ I couldn’t think of anything really bad I had done recently, so I was not unduly worried, but when he said in a loud voice he had a document for Alexander Adolphus Dumfries Henshaw I wanted to die. If only the floor would open up and swallow me. I was so shaken that I did not hear my mother’s gasp of joy, or the policeman saying what pleasure it gave him to request, on behalf of the Lincoln County Magistrates, if I could attend an official ceremony to be presented with the Royal Humane Society’s award for saving a boy’s life in the River Witham the summer before. I remembered the incident well, but was embarrassed to read the citation and the press reports, and thought they grossly exaggerated the true situation. Inwardly I wanted to say it was not strictly true and there were others involved as well as myself, but I hadn’t the courage. The press reports said I dived fully clothed into the river and saved the boy as he was going down for the third time. The true story is that I heard the boy yell whilst I was dressing on the bank. I rushed on to the wooden ferry moored near the edge of the water, and paused to take off my trousers and shoes as they were new, and mother had said she would tan me if I messed them up. When I dived in the boy had panicked and I had a job to hold him up, but did so as I trod water frantically; whilst I was working slowly towards the bank, other boys rushed in and grabbed us both, The most gratifying part of the whole incident to me was when I went again to the Lincoln Magistrates Court and heard, not ‘Henshaw’ called, but, ‘Would Master Henshaw kindly step forward, please?’

During that period of my life, water and I seemed to go together, for the next summer I was at Trusthorpe, on the East Coast, when someone rushed up to me one evening and said, ‘There’s a dog in the Grift Drain, drowning.’ I ran on to the beach right away, and saw a small crowd watching a little Yorkshire terrier being swept back and forth as the tide surged up and down the Grift sea defence drain-run, really a large wooden open-faced tunnel on the seaward side, disappearing into the sandhills as a tunnel to link up with the land on the other side, from which it drained all the water. I knew the tunnel well, for in my more daring moments, and when the tide was going out, I had paddled a canvas canoe down it and out to sea. I realised at once that unless the dog was brought out it would be plunged into the tunnel with a large wave and that would be the end. Everyone was making suggestions how to reach the dog, but no one was doing anything, and the old lady who owned it was crying bitterly. I stood it so long, and then without really being able to help myself I slipped off my shirt and boots before anyone could stop me and jumped into the racing drain. I grabbed the small dog in my hands, waited for a wave to surge me upwards and as I did so held the dog up so that those on the side could reach it. Now I was in trouble, but whereas no one had been doing anything for the dog, several men rushed into action when they saw me in difficulties. By the time I was too near the tunnel entrance for comfort and I was a very relieved boy when two men were able to lean over the drain wall and grab me before another wave surged me under. My father played hell over this incident when he heard, but I could see he didn’t mean a word of it, and in any case the pathetic little letter I received from the old lady made it all worthwhile.

My father was a great adventurer. He was one of a very large family, and at the age of sixteen ran away to America, landing with thirty shillings in his pocket. The first winter he spent in a lumber camp, but as the company owning the camp went bankrupt and the weather was bitterly cold, he had to stay there living on bad flour, bilberries and pork. It was not often he spoke of his early days, but when he did I hung on to every word. He trekked off into the Hudson Bay territory and at one time was alone on snowshoes with only a rifle and a little food, and the nearest white man was nearly a hundred miles away. Once he had a huge Scandinavian draw a knife on him, and as he lunged with the knife, my father hit him with all his strength, knocking him out; he took the knife from the inert body and kept it as a souvenir. After a long and often distressing period in which my father said he had never suffered nor worked so hard in all his life, he met by chance an old prospector who took a liking to him. They had the unbelievable luck to discover a silver mine which enlarged considerably the original thirty shillings he had landed with in America, enabling him to return to England a richer and more experienced man.

I loved to get into an escapade with my father, who sometimes had bright ideas which went wrong. He once thought that a fleet of barges would solve some of the transport problems in his business, so he hired a sea captain to tow three barges on to the Frieston Marshes near Boston. The calibre of the sea captain may be judged by the fact that with a heavy-gauge hemp rope he tied one of the barges tight up to the Boston wharf at high tide and left it; when the tide dropped at least fifteen feet the barge dangled from the wharf with one end under the water like a black sausage on a butcher’s hook. We eventually started down the River Witham in the tug, towing all the barges in a string aiming to reach the marshes at high tide, where the tug would run the barges as near to the shoreline as possible; then we would return with the tug to Boston. Unfortunately it didn’t work out that way. We got rid of one of the barges, but then as we were going full blast with the next one the tug gave a sudden lurch which flung all of us on the deck into a heap, and we came to a sudden but definite stop. We were aground and there was nothing we could do about it until the next tide. We all went below, but as the boat was at an acute angle the quarters were very uncomfortable; the fire also smoked badly and we began to feel rather like badly packed kippers. My father suggested that we try to walk over the marshes and reach Frieston on foot, but the tug captain said it would be dangerous and wellnigh impossible. We stuck it out for an hour or so, but I could see my father was getting restless and working up to something. Finally he said, ‘You stay here, Alex, I’ll see if we can reach the shore on foot.’ I said I could swim and jump, and where he went I would go. I shall never forget that walk over the marshes, with the tide running out of the almost foll creeks and each of us walking over the samphire in the dim light, searching for a firm spot where we hoped we could jump across. If one of...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 1.5.2012 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Natur / Technik ► Fahrzeuge / Flugzeuge / Schiffe ► Luftfahrt / Raumfahrt |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Technikgeschichte | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Psychologie | |

| Technik ► Fahrzeugbau / Schiffbau | |

| Technik ► Luft- / Raumfahrttechnik | |

| Schlagworte | blue riband • Cape Town • Comper Swift • Leopard Moth • Merlin engine • Percival Mew Gull • pre-recce • Shuttleworth • solo records |

| ISBN-10 | 1-84797-408-2 / 1847974082 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-84797-408-2 / 9781847974082 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 4,2 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich