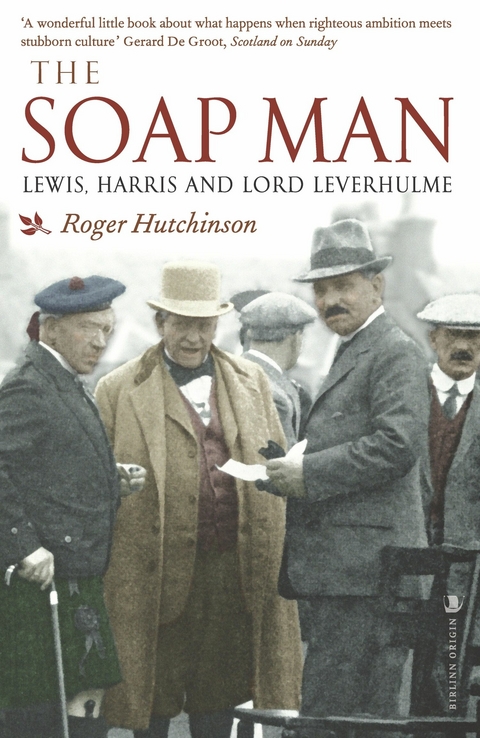

Soap Man (eBook)

256 Seiten

Birlinn (Verlag)

978-0-85790-074-6 (ISBN)

Roger Hutchinson is an award-winning author and journalist. After working as an editor in London, in 1977 he joined the West Highland Free Press in Skye. Since then he has published thirteen books, including Polly: the True Story Behind Whisky Galore. He is still a columnist for the WHFP, and has written for BBC Radio, The Scotsman, The Guardian, The Herald and The Literary Review. His book The Soap Man (Birlinn 2003) was shortlisted for the Saltire Scottish Book of the Year (2004) and the bestselling Calum's Road (2007) was shortlisted for the Royal Society of Literature's Ondaatje Prize.

In 1918, as the First World War was drawing to a close, the eminent liberal industrial Lord Leverhulme bought - lock, stock and barrel - the Hebridean island of Lewis. His intention was to revolutionise the lives and environments of its 30,000 people, and those of neighbouring Harris, which he shortly added to his estate. For the next five years a state of conflict reigned in the Hebrides. Island seamen and servicemen returned from the war to discover a new landlord whose declared aim was to uproot their identity as independent crofter/fishermen and turn them into tenured wage-owners. They fought back, and this is the story of that fight. The confrontation resulted in riot and land seizure and imprisonment for the islanders and the ultimate defeat for one of the most powerful men of his day. The Soap Man paints a beguiling portrait of the driven figure of Lord Leverhulme, but also looks for the first time at the infantry of his opposition: the men and women of Lewis and Harris who for long hard years fought the law, their landowner, local business opinion and the entire media, to preserve the settled crofting population of their islands.

Roger Hutchinson is an award-winning author and journalist. After working as an editor in London, in 1977 he joined the West Highland Free Press in Skye. Since then he has published thirteen books, including Polly: The True Story Behind Whisky Galore; an acclaimed literary biography of James Boswell; a definitive history of the 1966 World Cup; and a life of Aleister Crowley. He is still attached to the WHFP as editor and columnist, and has written for BBC Radio, The Scotsman, the Guardian, The Herald and the Literary Review. He lives on the Hebridean island of Raasay.

1

THE UNIVERSITY OF LIFE

Port Sunlight was the embodiment in bricks and mortar of the social and industrial philosophy of William Hesketh Lever. In 1887 it was an unpromising windswept area of marshland on the eastern coast of the Wirral peninsula, overlooking Liverpool and the broad Mersey estuary. In search of a new site for his expanding manufactory that year, Lever had boarded stopping trains up and down each bank of the Mersey from Warrington to the sea. He arrived at this reach of sodden fields and clutch of ramshackle shanties named Bromborough, turned to his companion and said: ‘Here we are.’1

Thirty years later there were those who chuckled at Lever’s apparent naivety in buying for development 770 square miles of Hebridean bog and stone. They may not have been familiar with Bromborough in 1887. ‘It was mostly,’ said one contemporary, ‘but a few feet above high water level and liable at any time to be flooded by high tides and thus to become indistinguishable from the muddy foreshores of the Mersey. Moreover, an arm of Bromborough Pool spread in various directions through the village, filling the ravines with ooze and slime . . . it did not, at first sight, seem fitted for human settlement.’2

One year later, in 1888, William Lever’s wife Elizabeth cut the first wet sod out of the Bromborough turf, the shanties and cabins and the very placename itself were quietly removed, and Port Sunlight – christened in honour of Lever’s celebrated brand of household soap – slid optimistically onto the map. There were hard-headed business reasons for this relocation, insisted Lever characteristically at the banquet in Liverpool which followed the turf-cutting ceremony. Bromborough/Port Sunlight was beyond the grasp of Liverpool’s harbour dues, saving him four shillings and tenpence on every ton of tallow. The festering mire of Brom-borough Pool could be converted to an anchorage with straightforward access to the shoreside soapworks. And that very anchorage in the sheltered waters of the inner Mersey River would release Lever Brothers from their expensive dependence on rail haulage. He could export his cargo by ship to the grimy, soap-hungry hordes of late-Victorian London. That might teach the railways to become competitive, and William Lever was ever in favour of teaching others the necessity of competition.

What was more, Bromborough came cheap. Who else in their right mind would bid for such a waterlogged wasteland on the depressed southern outskirts of Birkenhead? He walked straight into a buyer’s market; into negotiations with local landowners who were delighted to exchange their unproductive swamp for a handsome handout from the nouveau riche. William Lever initially bought 56 acres at Bromborough. By 1906 he had 330 acres of the place. Ninety of those acres were occupied by the Lever Brothers’ industrial plant. A further 100 acres were held in reserve. And 140 acres of reclaimed land were devoted to the mock-Tudor houses, gardens, broad avenues lined with spreading chestnut trees and fluting with birdsong, streams and quaint stone footbridges that comprised the model workers’ village of Port Sunlight.

William Lever was far from being the first such improver. The notion that capitalism’s servants might enjoy longer, healthier and more productive lives if released from the fearful urban stews had been proposed since the earliest years of the Industrial Revolution. Seventy years before Lever first set eyes on Bromborough Pool the socialist Robert Owen had constructed a workers’ mini-state at New Lanark Mills, and had recorded to his great satisfaction improved per capita production. In 1851 the wool-stapling millionaire Titus Salt had built a haven of sanitary terraced housing and schools for his workers beside the River Aire in Yorkshire. Even Queen Victoria’s lamented consort Albert had involved himself in the design and construction of new dwellings for the working Londoner.

Sir Titus Salt, Lord Mayor of Bradford, and Prince Albert were, unlike Robert Owen, no proto-communists, and neither was William Hesketh Lever (both Salt and Lever adhered, in fact, to William Gladstone’s Liberal Party). They were undoubtedly motivated by some sense of pity for the human flotsam of the nineteenth century. Lever cannot but have been aware of what a paradise a two-up-two-down semi-detached residence in Port Sunlight must have seemed to a worker’s family imported from the slums of Birkenhead. But socialist he was not. Trade union officials would repeatedly insist that Lever was the most autocratic and unreasonable employer in their considerable experience of autocratic and unreasonable employers. What agitated the Lancastrian industrialist William Lever was not the Rights of Man. ‘There could be no worse friend to labour,’ he would pronounce in 1909, ‘than the benevolent, philanthropic employer who carries his business on in a loose, lax manner, showing “kindness” to his employees; because, as certain as that man exists, because of his looseness and laxness, and because of his so-called kindness, benevolence, and lack of business principles, sooner or later he will be compelled to close.’3

This was not entirely logical. Benevolence and philanthropy and kindness are not automatically anathema – as Lever implied – to efficient ‘business principles’. But it was a typically uncompromising statement of intent, and one which would echo down his entrepreneurial years until the end of his life, touching and deeply affecting such distant quarters as West Africa, the Solomon Islands and the Outer Hebrides.

Profits came first. Even Port Sunlight, the young entrepreneur’s flagship venture, would have to pay its way before workers could be re-housed. The first twenty-eight ‘cottages’ (they were actually, by twenty-first as well as late nineteenth-century standards, reasonably-sized houses) would not be built until the soapery workplace was up and running. But once they were built the houses were model dwellings: strong, weatherproof, roomy and warm.

The price demanded of his workforce for such domestic luxury was their acceptance of benevolent dictatorship. The inhabitants of the New Jerusalem by the side of the Mersey would be asked to relinquish virtually all self-determination, and most of their collective rights, in return for a golden security in the young and infinitely promising twentieth century. Their employer, William Hesketh Lever, would become rather more than a dispenser of wage-packets operating in a free market of commodities and labour. He would determine not only the future and conditions of the industry which supported them all, but also the future and conditions of his workers’ private lives.

Lever saw no reason to be shamefaced or shy about this presumption. Why should he? ‘If I were to follow the usual mode of profit-sharing,’ he proclaimed, ‘I would send my workmen and work girls to the cash office at the end of the year and say to them: “You are going to receive £8 each; you have earned this money: it belongs to you. Take it and make whatever use you like of your money.”

‘Instead of that I told them: “£8 is an amount which is soon spent, and it will not do you much good if you send it down your throats in the forms of bottles of whisky, bags of sweets, or fat geese for Christmas. On the other hand, if you leave this money with me, I shall use it to provide for you everything which makes life pleasant – viz. nice houses, comfortable homes, and healthy recreation.” Besides, I am disposed to allow profit sharing under no other than that form.’

Eight pounds in 1890 was the equivalent of more than £500 at the start of the twenty-first century. It would have bought a lot of confectionery. The late-Victorian Merseyside proletariat would doubtless have preferred the opportunity to eat goose and drink whisky as well as live in comfortable homes. But it was given only the choice between decent housing and relative destitution. It opted naturally for teetotal Port Sunlight, a model village which had, on the order of its proprietor, no public house. For the late-Victorian Merseyside proletariat had suffered a hundred years of squalor, disease and early, miserable death. Having known nothing else, its priority was to stabilise itself in the face of a future which, however uncertain, could hardly be worse. Trades unionists may have heard Lever’s words and grumbled; doctrinaire socialists may have cursed him as a tyrant; but the bulk of his workforce scrambled to accept both his terms and the keys to his cottages.

Thirty years after Elizabeth Lever cut those first turfs at Bromboough, thirty years after William Lever told his employees at an early works outing that they must improve his profits and then trust him to improve their livelihoods, another group of British men and women 400 miles to the north of Port Sunlight would listen to identical sentiments. But the response of the people of the islands of Lewis and Harris would be so unanticipated, so unconquerable, so radically different that it broke the resolve of William Hesketh Lever, and in so doing seemed to break the man himself.

William Lever was born in Bolton on 19 September 1851. His father, James Lever, the scion of an old Lancashire family which had turned to trade, was a partner in a wholesale and retail grocery business. The Lever family was Nonconformist. James had met his wife, Eliza Hesketh, at chapel. They made their home in a three-storeyed Georgian terraced house in a comfortable middle-class district of Bolton. And there, in an improving smoke-free atmosphere of abstinence and duty, Eliza gave birth in quick succession to six girls. William was...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 14.6.2011 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Gesundheit / Leben / Psychologie ► Esoterik / Spiritualität | |

| Geschichte ► Allgemeine Geschichte ► Neuzeit (bis 1918) | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| ISBN-10 | 0-85790-074-9 / 0857900749 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-85790-074-6 / 9780857900746 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 997 KB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich