Family Romance (eBook)

400 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-28833-5 (ISBN)

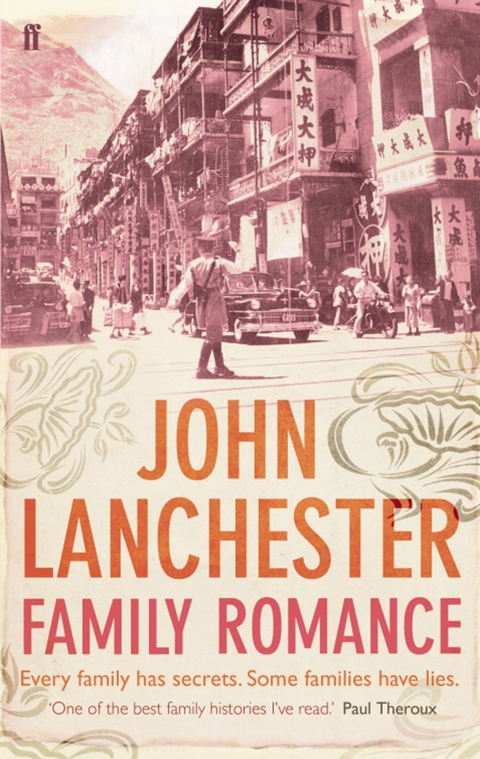

John Lanchester has written five novels, The Debt to Pleasure, Mr Phillips, Fragrant Harbour, Capital and The Wall, and three works of non-fiction: Family Romance, a memoir; Whoops!: Why everyone owes everyone and no one can pay, about the global financial crisis; and How to Speak Money, a primer in popular economics. His books have won the Hawthornden Prize, the Whitbread First Novel Prize, the E. M. Forster Award, and the Premi Llibreter, been longlisted for the Booker Prize, and been translated into twenty-five languages. He is a contributing editor to the London Review of Books and a regular contributor to the New Yorker.

In this acclaimed memoir from the award-winning author of Fragrant Harbour and Capital, John Lanchester pieces together his family's past and uncovers their extraordinary secrets - from his grandparents' life in colonial Rhodesia to his mother's time as a nun - with clear-eyed compassion. A true story of family intrigues, of secrets and lies, as they unfold across three generations.

A colourful, entertaining tale... this is a subtle and sensitive attempt at achieving self-awareness through an understanding of one's parents.

In this sympathetic memoir of his parents, novelist John Lanchester carefully reveals aspects of their lives they kept hidden from him... the real strength of this book - apart from it superb writing- is how Julia and Bill's qualities combine in their son.

A riveting write-up of his detective work, especially commendable for its care and compassion. It's a rare memoir that doesn't make you feel the need to shower off the bile afterwards.

Lanchester has found the extraordinary in s father's ordinariness and made for him, and for his mother, a memorial that deserves to endure. The prose of this multi-biography is exemplary... [it is] a profoundly important book that addresses the nature of love, of memory and of causation... this book matters - all the more so in this rushed and passing world.

The central story is interesting enough, but it is the writing that makes the book: the unassuming reasonableness of Lanchester's voice isoddly beguiling, and he offers myriad small solid insights into family life that are funny and painful by turns.

Superb writing... this is a wonderful and absorbing book, a psychological study of great insight.

From rural Ireland to Hong Kong, Madras to London, Lanchester traces his parents' slowly converging lives and fixes their character as poignantly and brightly as old cine-film... all families have secrets, but not all families are lucky enough to have a writer as generous and elegant as Lanchester to defuse the tick of their time-bomb power.

One of the most famous things ever written about family life is the opening sentence of Anna Karenina: ‘All happy families resemble one another, each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.’ It’s a magnificent line, so sonorous and resonant that it makes it easy for us not to notice that it isn’t true. Part of its falsehood lies in the fact that happy families aren’t especially alike, any more than unhappy ones are unalike. But at a deeper level, the falsehood lies in the idea that a family is either happy or unhappy. Life, family life, just isn’t that simple. Most families are both happy and unhappy, often intensely so, and often at the same time. A sense of safety can be a feeling of trappedness; a delight in routine can be suffocating boredom; a parent’s humour and unpredictability can be a maddeningly misplaced childlikeness – and, in many cases, the feeling is simultaneous. I was both happy and unhappy as a child, just as my parents were both happy and unhappy, and just as almost everyone else is.

Another way in which our family resembled everyone else’s was because we had secrets. All families have secrets. Sometimes they are of the variety that a family keeps from outsiders; sometimes they are the sort that a family keeps from itself; sometimes they are the sort whose presence no one consciously admits. But they are almost always there. People have a deep need for secrets. The question is what to do with them and about them, and when to let them go.

My parents’ ashes are interred in the graveyard of All Saints’ Church at Manfield in North Yorkshire. Neither of them had any connection with the place in life, and it is in that sense an arbitrary place for them to have ended up. My mother was born in Ireland, my father in Africa, and neither of them ever lived anywhere near Manfield. But they moved around a lot, and came to be people who didn’t have too strong a link with anywhere, so I don’t think the arbitrariness of the location is inappropriate. Besides, Manfield is where the Lanchesters’ grave is: my father’s father and great-grandparents, and then back again for two more generations, are all buried there. His grandfather is the only immediate ancestor to be elsewhere. Some of the graves have been shifted over the years, pushed up against the church wall to – among other things – make the graveyard easier to mow. But the Lanchesters’ grave has been spared that, and lies where it always has, under the south wall of the high-windowed, grim, eighteenth-century church.

‘It’s a cold place,’ my mother said to me, the day we buried my father’s ashes in the summer of 1984, a few months after his death. ‘I don’t like the idea of him being cold.’

‘It’s where he wanted to be,’ I said, which was true.

I didn’t, and don’t, have the same consolation about my mother’s ashes ending up at All Saints’. I interred them there in the summer of 1998, and it was a mistake. She didn’t want her ashes to go there, because she didn’t want to be cremated. In the immediate aftermath of her death, though, I was so upset that I didn’t read her will closely enough to notice its very first sentence: ‘I ask that my body be buried.’ It used to be an important piece of Catholic doctrine, that cremation was wrong because it prevented the body’s rising from death at the Last Judgement. But I am not a Catholic, and in my distress simply missed the statement and its importance. So I interred her ashes in the summer of 1998, in the same grave where she and I had put my father’s ashes fourteen years before.

That day, the day I interred my mother’s ashes, I had a sense of being oppressed by things I wanted to talk about and could not. The mistake I had made in having her cremated was on my conscience, but since I did not know the priest – had met him right there and then for the first time – I felt it would be too much to explain in the fifteen or so minutes we had together. There was also the fact, not at all important but very hard to get out of my mind, that the priest was wearing army boots and combat trousers under his cassock. I noticed this as we stood beside the grave reading a shortened form of the burial service. No doubt I wouldn’t have spotted it if I hadn’t already been looking down at the small hole in the grave, just big enough to cover the little wooden box that contained my mother’s ashes. I began to wonder if it would seem out of turn to ask why he was wearing combat clothes. Was it some new thing that priests did, making some point about being a soldier for Christ? I did hope not. And he seemed a nice, mild-mannered, gentle man, not the sort for wild evangelical gestures. Or perhaps it was me? Funeral rites often have an air of strangeness and unreality about them; sometimes you lose your hold on what is normal and what isn’t. I had a sudden, vivid memory of the day after my father died, when the local Church of England vicar came to the door to offer comfort. Because my parents had only just moved into the house, he had no idea who we were. My mother was somewhere upstairs, so I made tea. In a very English way we made small talk. Then he picked up a photograph of my father from the bookcase.

‘I hope you don’t mind me asking,’ he said, ‘but are you Jewish?’

It was about twelve hours since my father had died. I had been up all night dealing with police, ambulance men, and the doctor. I was numb to my bones, so numb I didn’t know quite what to say other than:

‘I don’t mind you asking, but no, I’m not Jewish.’

‘Oh,’ he said. Pause. ‘Because you look Jewish.’ Pause. ‘I hope you don’t mind my asking again, but was your father Jewish?’

By now wondering where this was going, I said, ‘No …’

‘Oh,’ he said. Pause. ‘Because he looks Jewish.’ Pause. ‘Because I’m Jewish.’

At this point he was visibly expecting me to break down and admit that I too was Jewish but had been too shy to admit it.

Standing by the family grave, I had a flashback to that moment. The Church of England seemed to generate a strange force field to do with eccentricity and embarrassment and nobody ever knowing quite what to say. It might be perfectly normal for a Church of England priest to be wearing combat clothes under his clerical outfit. But I found it hard to concentrate on the words of the service, there in the cold Yorkshire graveyard.

In the event, the nice priest cleared things up, just after putting the clod of earth over the small wooden box containing my mother’s ashes.

‘Thought I should say about the outfit,’ he said. ‘I serve in the Territorials. Mechanical engineering. I’m off now to repair some motorbikes.’

‘Thanks,’ I said.

‘What would you like to have written on the grave?’ he then asked. And that was the next thing I did not want to talk about. The gravestone lists the names and ages of all the Lanchesters buried there. But both my mother’s name and age were now in question. A month before, five days after she died, I had found out that both the name and date of birth I had known my mother by were false. What I didn’t know was when or why or how she had taken a false identity, and what it meant for the story of her life, and my father’s life, and mine. I also knew that finding all that out was going to take some work. My immediate dilemma was whether to give the dates that corresponded to her real identity – which contradicted all the documents I had had to show in arranging the interment, and also contradicted all the stories she had told about her life – or to tell the truth. The story of our lives is not the same as the story we tell about our lives.

‘Can I get back to you on that?’ I asked the priest. He looked a little surprised, but he said, ‘Of course.’

So I set out to find the story of my mother’s life, which is also the story of my father’s life, and, to an extent far greater than I realised when I began this journey, the story of mine too. This book is that story. It has involved three kinds of detective work for me. One is close to actual detective work: finding out what my parents did, and what was done to them. This is fairly straightforward for my father, and not at all so for my mother, who covered her traces well and never gave anything away. For my mother’s earlier life, my main sources have been conversations with family members; a short account of my mother’s life written by my aunt Peggie and followed by a formal interview with her; and a set of letters that Peggie gave me. For the later part of my mother’s life, for my father’s life, and for my parents’ lives after marriage, a camphor-wood chest full of family papers has been my primary source. The second kind of detective work is emotional: trying to find out what they felt about what happened, and why they did the things they did. And then there’s the third strand, which is trying to work out what I feel and think. That is something we all need to do about who we are and where we come from. I believe that everyone should do this, or something close to it. We should all know our family’s story, all the more so if nobody tells it to us directly and we have to find it out for ourselves.

But before I tell the story of our family, I need to explain a little about what my parents were actually like.

I don’t remember how I found out that my mother was, or rather had been, a nun.

When you are a child, the way you learn something attaches itself to the thing you’ve...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 2.2.2012 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik ► Regional- / Landesgeschichte | |

| Schlagworte | Capital • family memoir • generational memoir • hong kong memoir • peter carey wrong about japan • sebald vertigo |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-28833-2 / 0571288332 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-28833-5 / 9780571288335 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 5,1 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich