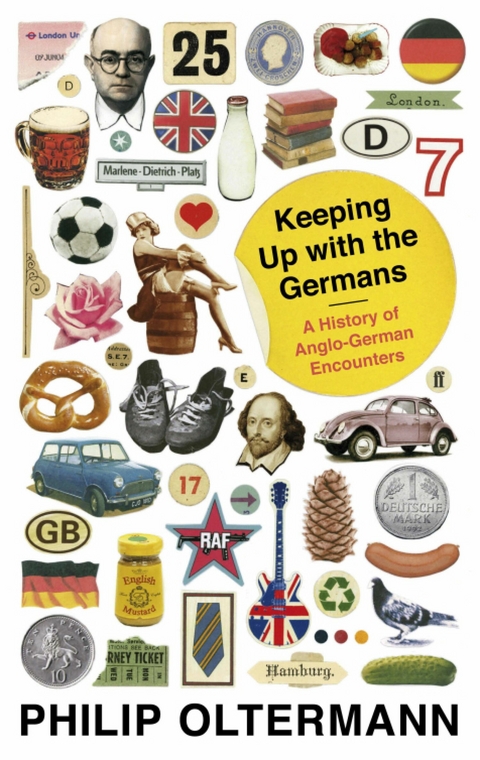

Keeping Up With the Germans (eBook)

304 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-27991-3 (ISBN)

Philip Oltermann grew up in Schleswig-Holstein and studied English and German literature at Oxford University and University College London. As a journalist he has written for Granta, the London Review of Books and the Guardian, for whom he is the Berlin Bureau Chief. He is the author of Keeping Up with the Germans (2012) and tweets at @philipoltermann. He now lives in Berlin with his family.

In 1996, in the middle of watching an ill-tempered football match between England and Germany, Philip Oltermann's parents tell him that they are going to leave their home city Hamburg behind and move to London. Inspired by his own experience of both countries, Philip Oltermann looks at eight historical encounters between English and German people from the last two hundred years: Helmut Kohl tries to explain German cuisine to the Iron Lady, the Mini plays catch-up with the Volkswagen Beetle, and Joe Strummer has an unlikely brush with the Baader-Meinhof gang. Keeping Up with the Germans is a witty look at the lighter-side of Anglo-German relations over the last 100 years.

Philip Oltermann was born in Schleswig-Holstein but moved to England when he was 16. He has written for several English and German newspapers and magazines, including Süddeutsche Zeitung, Granta and the Guardian, where he now works as an editor.

I don’t remember much about the day we arrived in England. I don’t remember whether we arrived in the morning or the evening, whether it was rainy or sunny, whether it was cold or hot, whether we took the train from the airport into town or a taxi. I do, however, know that I was in a bad mood, and that we arrived on a Sunday, because that same evening one of my father’s new colleagues had invited us for a welcoming meal which she announced as ‘a Sunday roast’ when we stepped into her house. We had barely taken off our jackets when our host – all wavy coiffured hair and buck teeth – hugged us emphatically and tried to kiss me on my cheeks. She had accompanied the words ‘Sunday roast’ with a showy movement of the hands, like a butler lifting a silver dish cover, conveying an impression of ceremony and theatre. A Sunday roast, this hand movement tried to say, was not like any other meal.

We sat down at the dinner table and tried to converse politely in broken English. I was confused when the meal eventually arrived. The contents of my plate looked something like this: three thin, very well done slices of beef, four stems of broccoli, eight roast potatoes, all collapsed on top of each other like weary travellers at the end of a long journey. Spread around the plate, a pool of very thin brown sauce. Copying our hosts, we had dropped generous spoonfuls of horseradish sauce and bright yellow mustard onto either side of the plate. Mixing these pastes (they called them ‘condiments’) with the main meal, however, was a bad idea, as my father found out the hard way. His eyes were watery and bloodshot when he eventually stopped coughing. Paradoxically, the fact that the condiments were spicy didn’t actually mean that the meal itself was very flavoursome. In fact, the further you worked your way to the heart of the dish, the blander the flavours seemed to become – by the end, I found myself gnawing on an extremely stringy, dry morsel of beef. This appeared to have been a deliberate choice on behalf of the cook in charge, because no attempt had been made to trap the natural flavours of the meat by sealing it. Nor had the vegetables’ natural crunch been maintained. The sauce or ‘gravy’ was so bland as to not really be a sauce at all, but a further attempt to water down the flavours contained in the food. The whole thing reminded me of a picture painted with watercolours, or a song played on an unplugged keyboard.

Our hosts tucked into the roast as if it was manna from heaven. ‘Yummy yummy in my tummy’, the son of the family said after he had put the first forkful in his mouth. As he threw himself with glee into the pile of limp flesh on his plate, I noticed that the boy’s face looked both bloated and slightly bloodless. Was this what English cuisine did to you? I turned to look at his father. The corrosive effects of the national diet were visible here too, for the man had a red, bloodshot nose and a rapidly receding hairline, as well as crooked, yellowing teeth. I was also distracted by his table manners. In Germany, my parents had always insisted that I held my cutlery in the correct manner: using the knife in my right hand as the brush to the dustpan of the fork in my left. The English, however, used the fork as a kind of stabbing device, with the knife then being used to jam more food into a mini-kebab of roast beef, potato and broccoli. The English ate angrily and with no apparent enjoyment of the process of consumption, washing down barely chewed mouthfuls with hasty gulps of liquid.

Back at home, we usually had our dinner with Apfelschorle (tart apple juice diluted just enough with fizzy water) or, on special occasions, Spezi (Coca-Cola mixed with Fanta). Here, our hosts served our food with a drink that increasingly manifested itself to me as a potent symbol of the English national character: a lukewarm glass of tap water.

*

Through the ages, a number of abstract concepts have been associated with Britain and England in the German mind: democracy, independence, originality, eccentricity. They are loose associations, which will vary between regions; the distinction between ‘England’ and ‘Britain’, for one, has never been particularly consistent among Germans. On the whole, though, they used to be positive qualities: at various stages in history we have looked up to the English as pioneers in politics, industry or culture, or even just revered them as beacons of moral conduct. But these days ‘bad food’ is always at the top of these lists, and it is still surprising how few English people are aware of this. They have a vague notion that the French might not rate English cuisine very highly, but the Germans? Land of sausage and sauerkraut? Food is reliably the German’s first concern when you mention that you live in England. ‘You poor thing!’ ‘Is the food really that bad?’ ‘No wonder you look so skinny.’

German food, like English, traditionally consists of a diet of boiled meats, potatoes and conserved veg, but conceptually speaking, the approach is very different. German sausages have a bad reputation abroad, mainly because their poorest specimen, the frankfurter, is also the most widely known. Yet the frankfurter’s more adventurous cousins, the Nürnberger, Thüringer or Krakauer, can be a veritable feast for the tastebuds: be they smoked, roasted or infused with herbs. The Currywurst, a sausage doused in spicy curry ketchup which is finally becoming recognised as the country’s true national dish, speaks of a deep yearning for exotic spice and oriental heat. Even more traditional German cuisine is full of good intentions and surprisingly bold flavours. You can get cumin-spiced bread in every bakery, liquorice-and-chocolate lollipops in many cornershops and pepper-flavoured biscuits every Christmas. The classic German Christmas Stollen is still an archetype of how a good meal should be constructed: a firm yet not too sweet cake dusted with icing sugar, whose taste intensifies as you chew your way to the core, with your teeth eventually sinking into a rich goo of marzipan, candied fruit, pistachio and poppyseed. Flavour awaits you at the centre, that is the key.

Other regional fare attests to a maverick streak in German cooking: traditional north German meals include a bacon, bean and pear stew, black sausage with potato mash and apple puree, or one of my all-time favourites: a revolting-looking salt beef and potato mush with pickled beetroot and fried egg called Labskaus. I got very excited when my father told me once that Labskaus was the traditional comfort food of seamen like his father, and that its culinary tradition had been kept alive only in elite seafaring hubs. In Liverpool in the north of England an entire people were apparently named after the dish. Yet when I tried my first English ‘scouse’ years later, I was left with the same underwhelmed and undernourished feeling I had after my first English roast.

*

My parents wouldn’t have any of this. As we drove to our hotel after dinner, they could not stop going on about the moreish crunch of the potatoes and the fantastic zing of the horseradish. ‘Ganz köstlich!’ Criticism of the roast was verboten.

Like many northern Europeans, they were already closet Anglophiles before we made our move. It had taken a mere scratch to the surface for them to break out in a positive Anglomania. Over the next few days, bags of salt-and-vinegar crisps appeared in the cupboards of our self-catering apartment and cans of bitter invaded the fridge overnight. In the mornings I would wake up to the smell of fried bacon and baked beans. Everything authentically English had to be tried at least once: shepherd’s pie, toad in the hole, even the unique delicacy that is Marmite spread on a toasted slice of mass-produced white bread – yet another example of the inability to synthesise extreme flavour and extreme blandness into a coherent culinary experience.

Perhaps what irritated me wasn’t the food at all, but the fuss that my parents made about it. Until we moved to England, ‘making a fuss’ was not really something I had thought my parents capable of. My childhood was marked by a near-complete absence of open conflict or raised voices, in part because I was the youngest of four children and my parents were already well equipped for the traumas and tantrums of adolescence by the time I reached my teens. In other families I knew there were constant complaints about the behaviour of an unruly brother or a bossy sister, yet in our household relations were rarely too hot or too cold, but always perfectly adjusted to a pleasant room temperature. Moving to England threatened to change this delicate balance. The plan was that we would spend the first week visiting a number of schools within the London commuter belt and look at flats in the same area. In the interim, my father’s company provided us with a small flat near Mortlake in west London: a soulless place that not only smelled of grandparents but was also extremely small. For the first time in my life, I was spending large periods of time with my parents on my own, and without my older sisters and brother as a buffer, I began to worry that the atmosphere might soon turn toxic.

My mother and father had been born in adjacent villages on the stretch of land along the river Elbe known as das Alte Land, the old land. Yet in spite of the proximity of their birthplaces, their natural characters could hardly have been further apart. My mother was born into a family of seven children and had trained as a...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 31.1.2012 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Geschichte / Politik | |

| Reisen ► Reiseberichte | |

| Reisen ► Reiseführer ► Deutschland | |

| Reisen ► Reiseführer ► Europa | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Kulturgeschichte | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Soziologie | |

| Schlagworte | Britain and Germany • britain vs germany • Christopher Isherwood • christopher isherwood germany • german genius • germany memories of a nation • getting to know the germans • mini volkswagen beetle • miranda seymour • noble endeavours • noble endeavours miranda seymour |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-27991-0 / 0571279910 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-27991-3 / 9780571279913 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 356 KB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich