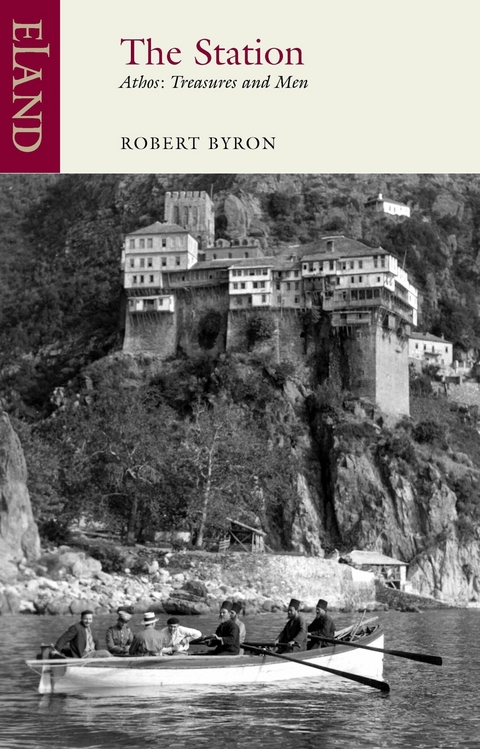

Station (eBook)

304 Seiten

Eland Publishing (Verlag)

978-1-78060-237-0 (ISBN)

?The Station follows three high-spirited young men visiting the monasteries on Mount Athos in 1927. They examine treasures and sketch the courtyards and those who live in them. They swim ecstatically off the sparkling, deserted beaches, climb mountains, talk and share meals with monks and transcribe these conversations with relish. For life is very different for a celibate hermit on Mount Athos. Time has no meaning: the Son of God, His Virgin Mother, the Angels and the Saints are all living creatures of flesh and blood, and the Pope is a heretic. This slim book was little short of revolutionary in its championing of Greek Orthodoxy and Byzantine civilization, reversing centuries of western prejudice. It was the first of Robert Byron's travel books, revealing the flashing wit, bravery, passion and astonishing powers of visual observation which made him such an exceptional witness.

The sun, admitted at eight o’clock, struck the doors of the cupboard opposite with a meaning that sent a tremor through the nerves and a ball of air into the pit of the body. Over the bed the fringes danced response to a quickened heartbeat. For the day of departure had dawned; day, in another sense, of return.

That afternoon I proceeded to London, and arose next morning to shop. The manager of that imperial institution, Fortnum and Mason’s, improvised poems on the contents of the saddle-bags. Six-pound tins of chocolate, two of chutney, a syphon brooding like a hen over its sparklets in a wooden box, pills, toilet requisites and stationery gradually accrued, together with the ink in a tin case from which these magic words pour. But to devise chemical armour against the insects which await with hideous patience the infrequent tenants of those musty guest-rooms, defied the ingenuity of every pharmacist from W.2 to E.C.4. I am fortunate, however, in possessing some revolting physical attribute, which prevents me, though not impervious to tickling, from being bitten.

At 10.51 on Friday, August 12th, I left Victoria, surrounded by suit-case, kit-bag, saddle-bags, hat-box (harbouring, besides a panama, towels and pillow-cases), syphon-box, and a smug despatch-case that contained a lesser-known Edgar Wallace and credentials to every grade of foreign dignitary, from the Customs to the higher clergy. Only as the train started did I discover the loss of the keys to these receptacles. Fortunately the carpenter of the Channel boat was able to provide substitutes for all but the suit-case. Meanwhile, troubles fell away as the pages of perhaps the greatest master of English fiction disclosed the appalling misdemeanours of Harry Alford, 18th Earl of Chelford. These were tempered with the items of the Central European Observer, a periodical new to my journalistic appetite, whose title had peeped like a succulent strawberry from a cabbage-bed of Liberal weeklies and Conservative quarterlies.

The Channel was rough; but with the undoing of the luggage, the plying of the carpenter with beer, and the delightful spectacle of an arrogant humanity draped about the seats in green and helpless confusion, the passage passed unnoticed. Happiness untrammelled was restored at the sight of the rotund coaches of the Train Bleu. For itinerant comfort, the palm must ever remain with this serpentine palace. Curled against the garter-blue velvet of a single compartment, the French afternoon whirred past me in comatose delight. At length came Paris, the clumped ova of the Sacré Cœur standing high and white against copper storm-clouds. Slowly we shunted round the ceinture amid those intimacies of slum-life presented by the main line traverse of any great city: hopeless figures gazing in immobile despondency through the importance of the train at their own troubles; children roving the open spaces on tenement balconies; garments sexless, patched, one inevitably Tartan, listless on their lines; healthy plants and flowers rendered pathetic by environment; the whole gamut of man’s misery, so it seems to the looker. At the Gare de Lyons the train doubled itself, gathered up its passengers, and started for the south.

Dinner was epic. Sleep cradled in the clouds. Morning broke with Avignon. And the sun rose over a barber’s chair at Marseilles.

It remained to open the still fastened suit-case. Up a neighbouring street a locksmith of stupendous proportions and his shrewish wife set about to make a key for it. At the end of an hour their patience was exhausted and the upper catch was loosened from the lid by a drill. Now opened, it needed a strap to close it again, in search of which, to the speechless indignation of the shrewish wife, the locksmith and I left the shop. With the advent of the ‘zip-bag’, rational instruments of cohesion seemed to have become extinct. We hurried from street to street, the locksmith scorning my idea of taking a taxi – he never did – and pausing now and again to direct my attention to a bevy of nude nymphs clinging by some process of stomachic suction to the boulders of a municipal fountain. Our quest fulfilled, I piled body and baggage into a diminutive motor, and, telegraphing to herald my arrival in Athens, descended to the docks.

The Patris II lay silent and empty. I was shown my cabin, then left to explore its dark recesses. It was morning; the stewards were hardly aboard; and it was with difficulty that as much as beer and a sandwich were persuaded from the bar. But as the afternoon advanced, peace dispersed. Crowds on deck waved to crowds on shore, serried against the endless vista of warehouse brick. Two women fiddlers and a male harpist scraped discords to the hot air. Ten yards away, the faded rhythm of ‘Valencia’ quavered from a ragged couple, haunted with memories of last year to which I was returning. A fat woman, the hazel of her bare arms emerging inharmoniously from petunia silk, began to cry. As the tea-gong thrummed we moved from the quay-side, threaded the enormous harbour, rounded the outer mole, turned, and sailed east.

The Patris II, a white boat, decorated by Waring & Gillow and sanitated by Shanks, is the pride of her line, which bears the same name as myself. First-class accommodation boasts a ladies’ room in dyed sycamore and pink brocade, a lounge in mahogany, a smoking-room, and a bar. The passengers were mainly Greeks, attired in the crest of fashion, and each endowed with sufficient clothes to last them without reappearance through the sixteen odd meals of the voyage. White trouser and mauve plus four flashed above particoloured shoe; new tie was child of new shirt; jewels glittered; gowns clung; lips reddened; and all continued to ring the changes in face of the increasing heat; while I lay about, cool and contemptible, in one shirt and a pair of trousers. Music was unceasing. Two pianos and a gramophone ministered to ‘fox trrott’ and ‘Sharléstoun’. While below, in the bows, the incantation of strings impelled the steerage passengers to lose their small-moustached, black-coated selves in a more reserved syncopation. Something inexplicably haphazard pervades Greek dancing: the slowly moving ring of peasants on the sky-line; the inspired solo of an Athenian wine-shop; the applauded pas-de-trois, kicking up the dust of a café circle at a wayside station, with a great trans-European express caught up in amazement; many scenes were hailed from oblivion by the sad rhythm. Till the blare of jazz brought back the West.

First-class society resolved into groups. Seated at meals on the captain’s right was Madame Venizelos, uttering words of patronage and comfort to such loose infants as toddled within her orbit. Paying court, on one side, was an ancient scion of the Athenian house of Mélas, a retired naval captain, bearing the magnificent appearance of an English duke of the ’forties, white beard and moustachios a-cock; on the other Sir Frederick Halliday, instrument of that permanent obstruction of the Athens streets, ‘Freddie’s Police’. The second stratum centred round a number of young men from the Greek colony in Paris, attired at all moments of the day for every variety of sport. At night there was dancing on the upper deck, which resembled a steeply pitched roof covered in treacle. Overhead, the southern moon hung like a huge gold lantern affixed to the mast, casting romance into the souls of the couples and a path of rippling light over the sea beneath.

The meals were served in the temperature of a blast-furnace, stirred to its whitest by the vibrations of electric fans. One and all were impregnated with the taste of candle-flame, the outstanding feature of that terrifying menace to the palate, ‘Greek food’ – though to me familiar as the smell of a cedar wardrobe to a boy home from school. At my side, thoughtfully placed by the head steward, sat a compatriot, who, after thirty-six hours’ unbroken silence, opened conversation with the words: ‘Do you perspaire much?’ Himself, he said, he was resigned to a dripping forehead. Some people, on the other hand, exuded even from their palms. Throughout the voyage we kept our table animated with discussion of the absorbent merits of respective underwears.

The ship was timed to arrive at Piræus on Tuesday afternoon. Though we had left Marseilles punctually, it was not until the evening of that day that even the western coast of Greece appeared, a shadowy outline. Gradually the mountain gates of the Gulf of Corinth, giant cliff and weathered obelisk, stood softly from the rippled sea, each face a rosy grey, and a luminous blue lurking in the shadow of each easterly cleft. A white blur on the shore bespoke Patras. A three-masted sailing-boat rode by. Astern, the sun lay poised on an indigo hill, like a fairy tinsel flower on a Christmas-tree. A last glimmer trickled down the waves; then only a glow in the sky remained, deepening the hills and giving life to a star in the green opposite. Themistocles, the barman, jangling gin and vermouth, rooted the emotion in the senses. Darkness grew. The dinner-gong rang and rang again. At length it ceased, leaving its hearers filled with that spice of devil-may-care which only extended defiance of a ship’s mealtime can induce.

The last evening on board was devoted to what the most...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 30.9.2024 |

|---|---|

| Nachwort | John Julius Norwich |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Reisen ► Reiseberichte |

| Reisen ► Reiseführer ► Europa | |

| Schlagworte | Art History • Byzantine culture • Greece • Greek Orthodoxy • holy mountain • Icons • Mount Athos |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78060-237-5 / 1780602375 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78060-237-0 / 9781780602370 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 3,7 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich