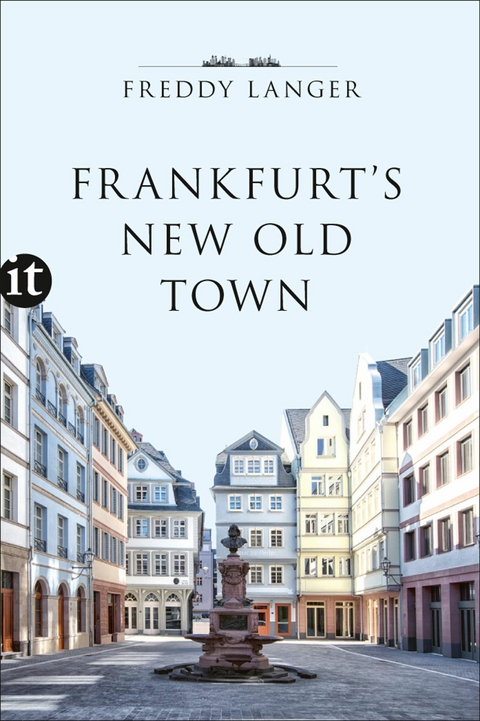

Frankfurt's New Old Town (eBook)

172 Seiten

Insel Verlag

978-3-458-76438-0 (ISBN)

Neo-Baroque and half-timbered romanticism in a city that thinks big, is growing upwards, and already seems to have the century-to-come in view? Hardly had the plans to recreate the bombed-out old city between the cathedral and the city hall of the Römer been drafted when the criticism began.

And yet, today native Frankfurters cannot curb their enthusiasm. Around the Hühnermarkt, by now one of the most attractive squares in the city, a new world has grown, which with its pubs, stores, and even a barber shop has not only become a magnet for tourism. It is as if, next to a new heart, Frankfurt's centre city has also received a new soul.

This lushly illustrated volume recounts the exciting history of the Römerberg, gives a summary of the various debates surrounding its reconstruction, and takes the reader along on a tour of one of the most beautiful and important buildings in the new district.

<p>Freddy Langer, geboren 1957, finanzierte sich das Studium der Amerikanistik, Film- und Fernsehwissenschaften mit Filmkritiken in der Frankfurter Allgemeinen Zeitung. Dass er nach dem Examen Redakteur im Reiseteil ebendieser Zeitung wurde, hat seine Begeisterung fürs Kino nicht bremsen können. Mittlerweile ist er seit 30 Jahren Redakteur der FAZ. Seine Buchpublikationen konzentrierten sich bislang auf Reisethemen und die klassische Fotografie. Der Band<em> Frauen, die wir lieben</em> erschien 2008 im Elisabeth Sandmann Verlag, 2019 folgt sein Buch <em>Frankfurts neue Altstadt</em>.</p>

2 Where Everything Began –

Kaiserpfalz Franconofurt's Holy Walls

The oldest photograph of Frankfurt is hanging in a light box on a wall beneath city hall and looks like a backdrop from Game of Thrones. It was taken on a bright sunny day, from the Sachsenhausen area out across the Main: in the foreground there's the river together with a few boats and jetties, and on the other shore the mighty palace Louis the Pious erected there in the middle of the 9th century. It is an imposing complex. On the left, the Königshalle with its bulky tower, as massive as a fortress, not too far away a basilica of a similarly well-fortified character, and in between, almost delicate, connecting the two buildings, a kind of gallery, punctuated by almost a dozen arches. Windows are few and far between–and as narrow as arrow slits, which could be due to the fact that glass was expensive back then. Though surrounded by palisades, it is enclosed in a setting that begs to be called idyllic: pastures, fields, and meadows spreading all the way to the thickly forested slopes of the Taunus mountain range on the horizon; in between, a dozen small villages of little thatched wooden cottages; craftsmen at work in their shops; a few people tending their garden plots; a shepherd with his flock; farmers and merchants transporting goods on oxcarts over cobblestone streets–only the appearance of a military encampment reminds us that times were not always that peaceful in the past.

Naturally, the colourful panorama is only a simulation created by a computer, made up of thousands of pixels, informed by a good portion of fantasy, but also by the conclusions that archeologists have drawn from a series of stone remains which were first found beneath the bombed-out wreckage of the Old Town after the air attacks of March 1944. Layer by layer was uncovered in the largest and most important urban excavation that Germany had ever seen. The cellar walls of medieval apartment buildings were identified as Carolingian foundations, and beneath them in turn the remains of a Roman bath house, together with a drainage ditch whose tiles were marked with the stamp of Mainz's 14th Legion. The site was dated to 75 CE. This fact also inspired researchers to create an image: that of a stopping place on a Roman road. It too hangs in a light box on the wall beneath city hall.

In this picture, the plateau is for the most part still unused. On the banks of the Main stands a massive stone structure, next to it is a military police outpost, on top of that, a little shrine and that very bath house whose heating system was excavated. The existence of the wooden bridge bobbing up and down on the water has not been scientifically verified, but it is believed that one existed. For this was where the important north–south connection between the Roman centres of Nida was, in that part of Frankfurt known today as Heddernheim, and the village known only by its incomplete name of …MED…, today's Dieburg. It would take more than half a millennium for the name Frankfurt to appear.

Nevertheless, Cathedral Hill (also known as Cathedral Island) had been populated since the Neolithic period. About 325 metres long and 125 wide, this slight elevation between the Main and its swampy branch, the Braubach, offered not only protection from high water but access to the ford across the Main. Which is why the Romans were here up until the Limesfall around 260 CE. A little while later, the Alemanni made whatever use they could out of the structure until they were in turn driven out by the Merovingians in the middle of the 6th century. But even as the small settlement around the palace gradually grew into a town, its ground plan was for a long time constricted to precisely this hill between the Main and the Braubach.

The land of the Franks was a country without a capital. The kings travelled from place to place, or more accurately: from palatinate to palatinate. And when during an eight-month stay here in 794 Charlemagne led the great synod with high-ranking religious leaders of the Kingdom of the Franks and some thousand more participants, leading to resolutions on religion, commercial policy, and accounting systems, he was the one who first used the city's name on a piece of parchment: Franconofurd, the ford of the Franks. This is the date of the city's founding, and young primary-school students still have the phrase ›Seven, nine, four: the year Frankfurt was born‹ drilled into them. The ruins of the imperial palace mark its birthplace, which is what makes it all the more surprising that it took so long to duly present it. For decades, the area was just a jumble of walls children used as a wild playground and homeless people as a place to find shelter. Opened in 1972 as an ›Archeological Garden,‹ the name was more than a little ironic. But now the remains of the walls are presented as relics, and not at all unjustly. As part of the Old Town's reconstruction, they have since the summer of 2018 been covered by the great hall of the newly erected Stadthaus event space and encircled by red sandstone walls, so that you feel like you are in a massive crypt. It's cool down there, but not cold or off-putting, which has to do with the light falling into the space from a row of windows and wall openings. Now and then it has a spectral effect.

The presentation is not immediately clear. Though people like to say the centrepiece is the Emperor's Hall, that gives the wrong idea. For even if the architecture emphasizes its longitudinal wall, and a shimmering brass roof with a diamond-shaped pattern mimics a ballroom, at first glance all the ancient and medieval relics seem to be jumbled up. The little columns, clay floor panels, natural stone, and plastered walls suggest an art installation rather than structural elements of a building. It is a kind of urban palimpsest. As to how fragile it is now considered to be, we need only note the little fences and walls protecting it all from anyone touching anything. Just like a museum, that's how valuable the ruins have become to the city. And just so that no one forgets where they are, the word ›Franconoford‹ appears on the wall six times in a row: in the same different variations as the name suddenly appeared in various 8th-century documents, maybe simply due to misspelling, but always in period script, the Carolingian minuscule that formed the basis for more recent fonts–Charlemagne also initiated educational reforms.

Three main rulers are connected to this place: Charlemagne, who with the synod granted the tiny town international importance. His son, Louis the Pious, who replaced the Merovingian court with the Carolingian palace in 822. And, in turn, his son, Louis the German, who made Frankfurt into a kind of capital of the East Frankish kingdom and built the Salvatorkirche, from which the cathedral later emerged. The fact that no one makes a fuss about any of the three kings is typical Frankfurt. With a high degree of self-confidence, it has always seen itself as a free city of burghers, which might also be why the archeological finds were treated so poorly for such a long time. And why the idea of Egon Wamers, the former director of the Archaeological Museum, to reconstruct the imperial palace's central building, the Aula Regia, was never really taken seriously. Instead, people spent decades making fun of the plan to reconstruct the half-timbered houses along the eastern side of the Römerberg, countering that it would be a better idea to reconstruct the Roman baths: people would enjoy them more.

Which is a good transition. For while the Franconofurd imperial palace has the stuff to become a signpost attraction for the city, the burghers have now begun to wonder how to feel about the Stadthaus covering the area. What's worse, a lot of people didn't want it to be built at all. Instead, a citizen's initiative by the name of SOS Cathedral-Panorama was arguing to preserve the ›open view of the cathedral‹ that had suddenly appeared thanks to all the construction between the cathedral and the Römer. A view that had never really existed throughout the course of Frankfurt's history. The cathedral had always been in the thick of things, towering out of the inseperable web of alleyways, houses, and rooftops, and up to today old Frankfurters refer to the cathedral as the mother hen, gathering her chicks around her. Be that as it may, the decision to build the Stadthaus,...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 17.2.2020 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Original-Titel | Frankfurts neue Altstadt |

| Themenwelt | Reisen ► Reiseführer ► Deutschland |

| Reisen ► Reiseführer ► Europa | |

| Schlagworte | Altstadt • Ancient Frankfurt • Architecture • Architektur • Bauwerk • Building • city center • Deutschland • Dom-Römer-Viertel • Frankfurt am Main • Frankfurt-am-Main • Frankfurt picturesque old town • Germany • historical center • Historical City • Historic part of a town • History Frankfurt am Main • Mit zahlreichen farbigen Abbildungen • old city • Old Frankfurt • reconstruction • Römer • Römerberg • Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt • Town Planning • Travel |

| ISBN-10 | 3-458-76438-0 / 3458764380 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-3-458-76438-0 / 9783458764380 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 23,9 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich