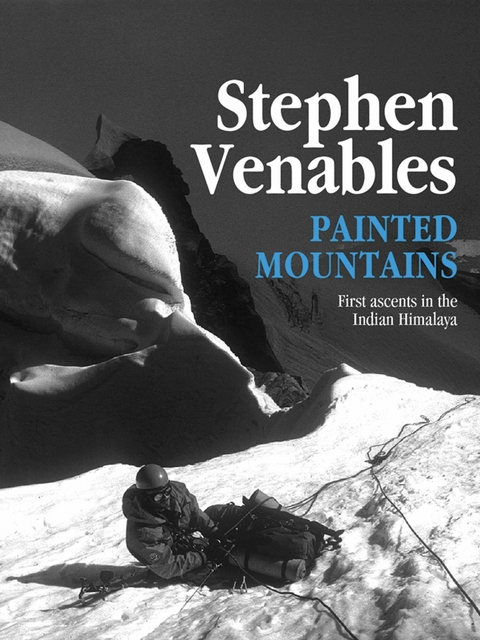

Painted Mountains (eBook)

200 Seiten

Vertebrate Digital (Verlag)

978-1-911342-94-6 (ISBN)

Stephen Venables is a mountaineer, writer, broadcaster and public speaker, and was the first Briton to climb Everest without supplementary oxygen. Everest was a thrilling highlight in a career that has taken Stephen right through the Himalaya, from Afghanistan to Tibet, making first ascents of many previously unknown mountains. His adventures have also taken him to the Rockies, the Andes, the Antarctic island South Georgia, East Africa, South Africa and of course the European Alps, where he has climbed and skied for over forty years. The stories of these travels have enthralled Stephen's lecture audiences all over the world. He has appeared in television documentaries for the BBC, ITV and National Geographic, presented for Radio 4 and appeared in the IMAX movie Shackleton's Antarctic Adventure. Stephen has also authored several best-selling books on climbing in the high mountains.

Snow began to fall at dusk. Inside the tent we struggled to cook supper. The stove was an old punctured tin can filled with smouldering lumps of dried yak dung. Our smart pressure stove had been abandoned many miles back, when we failed to obtain petrol for it. In the forest we had managed well, cooking on wood fires, but for three days now we had been above the tree line, forced to improvise, and I had felt slightly ridiculous climbing up to the Himalayan watershed with a large bag of yak turds tied to the top of my rucksack.

Now, on the evening of 11 September 1979, we were camping at 5,300 metres on the crest of the Himalaya, in Kashmir. That afternoon we had for the first time looked north to the brown desert landscape of Zanskar. We had planned to cross the Himalaya and continue through Zanskar to Ladakh; but one look down steep ice slopes, curving down out of sight on the far side, had been enough to deter us. Philip, my brother, had virtually no climbing experience and no crampons to cope with the hard, glassy, ice, so we had abandoned our plan and decided to return the way we had come. As evening was already drawing in and cold damp clouds were swirling around, we had stopped to camp where we were, on the ridge, pitching the tent on a small moderately level patch of snow. Now the wind outside, the horrible black fumes of yak dung augmented by diesel on our makeshift stove, and the cold, seeping insidiously through the tent floor, all intensified our feelings of failure and despondency.

The following day we set off back south. We walked down through grey drizzle and stopped in the evening to camp in a cave, eking out a pitiful meal of dried onions and mashed potato.

Morning transformed everything. The sky was blue; a meandering stream glittered silver in the sunlight; and, as we sauntered down through meadows of edelweiss and cotton grass, the air was filled with the vibrant twittering of a thousand songbirds. Suddenly, failure was forgotten and I could abandon myself to the exuberance of a radiant autumn morning.

We were following the curve of the stream down towards a lower valley, which would eventually lead us back to the Chenab river and the hill town of Kishtwar, where our journey had begun. Gradually, as we rounded a bend, a great mountain came into view, at first only the gleaming white summit, several miles to the south; then ice cliffs, rock buttresses and pinnacles revealed themselves until, finally, the whole mountain was framed in the V of our valley. It was an inspiring sight. The summit was a curved hump of pristine white snow; on either side, ridges fell away in a series of plunging towers; between the ridges, the North Face dropped in a single swoop of 2,500 metres to the valley. Only the elegant snow flutings of the summit ice field were in sunlight. Below that, the face was in shadow; steep slabs of granite, smeared with ice slivers and dusted with powder snow; below them a great barrier of ice cliffs, poised menacingly above more rock walls; further down still, a chaotic glacier tumbled darkly into the valley below us.

I looked back up to the summit, wondering why I had not taken more notice of it on our way up the valley a few days earlier. I knew from our map that it was c.6,000 metres above sea level (about 20,000 feet), quite low by Himalayan standards but, in the context of this Kishtwar region of Kashmir, where few summits exceed 6,000 metres, it was a magnificent mountain. A friend of mine had seen it the previous summer and had discovered that the local villagers called it Shivling, the phallus of Shiva, god of creation and destruction. There is another Shivling in Kashmir, a pillar of ice in a cave, revered by countless Hindu pilgrims. There is also another mountain called Shivling, 200 miles further south-east along the Himalayan chain; it was climbed by the India-Tibet Border Force in 1974, but this ‘Kishtwar-Shivling’ had never been attempted. On that September morning in 1979 I was in no fit state to climb mountains. After several weeks in the subcontinent, I felt weak and undernourished; and in any case this was a trekking holiday, we were not equipped for serious climbing. For the moment Kishtwar-Shivling was just something beautiful and inspiring to look at, a final reminder of the high peaks before descending to the forests of the Chenab gorge. Nevertheless, as a mountaineer I could not help being intrigued by the idea of trying to climb it. It looked very hard, harder than anything I had done in the Alps or during my first Himalayan expedition to the Afghan Hindu Kush. It would be a fascinating problem and I wondered whether I might return one day to find a way up to that remote gleaming summit.

We returned to England. Kishtwar-Shivling remained at the back of my mind as a vague possibility, a hypothetical scheme. The following summer some friends in Oxford asked to see my pictures of the Kishtwar region. They were planning their first Himalayan expedition and were looking for possible objectives. I showed them a photo of Shivling and they considered making an attempt but eventually opted for a technically easier peak, making the first ascent of Agyasol, a few miles to the south. Although I still had no serious plans for Shivling, I was secretly relieved that it remained unclimbed. I was also relieved to hear from the Oxford expedition that Shivling’s south side, which they had seen from Agyasol, looked steep and difficult – relieved, because if there had been an easy way up the back, much of the peak’s challenge would have been lost. There is something very exciting about a beautiful unclimbed Himalayan peak with no obviously easy route to the top. The south side might be slightly gentler, but there was not much in it, and I always returned to my pictures of the North Face, a great mixed climb on snow, ice and rock, a mass of intricate details forming a coherent architectural whole, like some huge and fantastic Gothic cathedral.

In the meantime, other events were occupying my time. In the summer of 1980 I joined an expedition to attempt a new route on one of the highest mountains in the world: the 7,850-metre Kunyang Kish. The mountain had previously only been climbed once, after three attempts, which claimed four lives. Our attempt on the North Ridge failed, but it was a moving and memorable experience. Phil Bartlett, Dave Wilkinson and I spent several weeks isolated amongst the vast glaciers of the Karakoram range, coming quite close to success on a route involving nearly 4,000 metres vertical distance between Base Camp and the summit. In comparison with Kishtwar, the Karakoram is a savage landscape and even the approach march had its dangers, as we discovered when we were caught in a terrifying rockfall in the Hispar gorge. On the mountain, too, there were frightening moments – two falls into crevasses, a near miss when an overhanging cornice of snow broke with a loud bang, and always the nagging fear of avalanches; but it was exhilarating to find a new route on the mountain. Twice we climbed to 6,800 metres; both times bad weather stopped us continuing to the top and we were held down by storms, marooned for several days in a snow cave, before retreating nervously down avalanche-wracked slopes.

Time ran out and we had to admit defeat. I returned to England weary and skeletal, ten days late for a new teaching job in York. Kunyang Kish had been such a compelling objective, in such magnificent surroundings, that we went back for a second attempt in 1981, hoping for better luck. In the event the weather was abysmal and we didn’t even reach the highpoint of the first attempt. Dave was so enthusiastic about the mountain that he had persuaded two more climbers to join us. One was an American, Carlos Buhler, who later took a leading role in the first ascent of the East Face of Everest. The other was one of Britain’s most experienced mountaineers – Dick Renshaw.

I first heard of Dick in 1973. I had just returned from my first summer alpine season, slightly disappointed with unambitious climbs. In Mountain magazine I read about two Yorkshiremen, called Dick Renshaw and Joe Tasker, who had spent the summer systematically climbing some of the most formidable north faces in the Alps. The following summer their names cropped up again and then, in 1975, they made the first British winter ascent of the North Face of the Eiger. Later that year, while a massive British expedition laid siege to the South West Face of Everest, with the assistance of sixty high-altitude porters, Dick and Joe drove out on their own in an old van to the Garhwal Himalaya, in India, to climb the South Ridge of 7,066-metre-high Dunagiri. This audacious climb of an extremely difficult route, by a two-man team with no back-up at all, received immediate acclaim in the climbing world and set the tone for a revival of lightweight expeditions. Dick published a superb article about the climb in Mountain, and reading between the lines of British understatement, one gained some idea of how hard he had been forced to struggle, in an epic retreat from the mountain, descending without food or water, delirious with exposure and suffering from appalling frostbite.

The following year, when his frostbitten fingers had recovered, he teamed up with Dave Wilkinson to make the first ascent, in winter, of the North-West Face Direct on the Mönch, one of the most serious routes in the Swiss Alps, which has still not been repeated. Dave asked him to come on the first Kunyang Kish attempt in 1980, but he had already...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 28.6.2018 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Freizeit / Hobby ► Sammeln / Sammlerkataloge | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport | |

| Reisen ► Reiseberichte | |

| Schlagworte | alpine climbing • A slender thread • climbing biography • climbing book • Everest • Expedition • famous climbers • first ascent • Higher than the eagle soars • Himalaya • K2 • Karakoram • Kashmir • Kishtwar-Shivling • Meetings with mountains • mountain climbing • Mount Everest • ollie • Rimo • rock climbing |

| ISBN-10 | 1-911342-94-0 / 1911342940 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-911342-94-6 / 9781911342946 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 5,6 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich