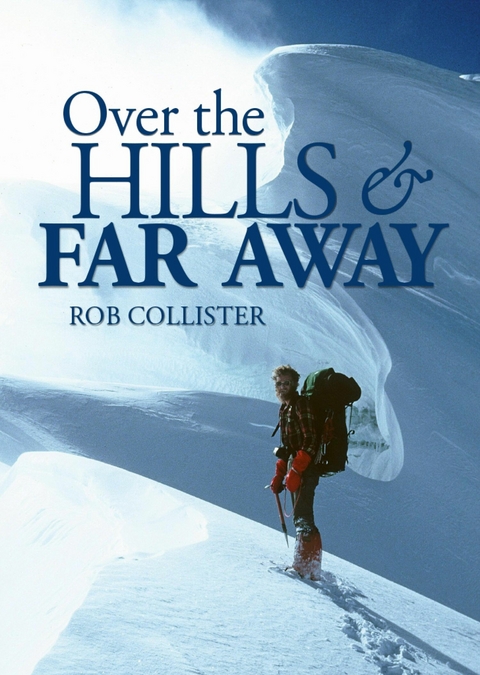

Over the Hills and Far Away (eBook)

192 Seiten

Vertebrate Publishing (Verlag)

978-1-911342-78-6 (ISBN)

Best known as an alpinist in his youth, Rob Collister was in his element climbing unnamed peaks in obscure corners of the Himalaya. In 1976 he qualified as a British Mountain Guide, and was one of the first British guides to ski the Haute Route with clients, soon taking parties to places such as Kashmir, Kulu, Alaska and the Lyngen Alps - long before they became popular destinations. Recently, concern about carbon emissions has led to a reduction in his expedition mountaineering and to the use of public transport to travel to and around the Alps. Throughout his career he has been based in North Wales, raising a family of three children with his wife Netti. He has been a trustee of the Snowdonia Society and the John Muir Trust, served as a nominated member of the Snowdonia National Park Authority and was president of the British Mountain Guides from 1990 to 1993. Rob has contributed to a number of anthologies and has written regularly for the Alpine Journal and other outdoor publications. His previous books include Lightweight Expeditions (Crowood Press), Over the Hills and Far Away (Ernest Press), and Snowdonia, Park under Pressure (Pesda Press).

'The whole trail has been orchestrated to make it possible for each one of us, in different ways, to be "e;touched"e; by wilderness'Over the Hills and Far Away is a collection of essays that demonstrates Rob Collister's thirty-year experience in mountaineering. From solo climbing in the hills of the Carneddau in Wales, to small group expeditions to Carn Etchachan, Forbes ridge and Grosshorn, Rob Collister can be found in the hills, whether it be running, climbing or skiing, inspired by the words of H.W. Tilman and Henry David Thoreau. This collection of essays tackles the theme of self-sufficient small group expeditions compared to the organised larger-sized ones, as well as displaying the timeless subject of litter disposal in summits by a fresh invasion of the mountains in Snowdonia and the conservation of the wilderness by the creation of schools such as Wilderness Leadership School. His sense of adventure is shown through his words and passionate descriptions, climbing out of conditions and finding a challenge in Alpine climbing. In Over Hills and Far Away we understand the importance of nature and appreciation of it. This book will expand your knowledge of modern world issues and it will leave you hungry for adventure in the hills.

I looked at my watch – it was only nine o’clock. What could have woken me so early? Then I became aware of Geoff regarding me sleepily. ‘I know what that bloke meant,’ he mumbled, ‘when he said that if you are dry you can’t possibly imagine being wet.’ That seemed an odd thing to say, but it was too much of an effort to think of a reply, so I just grunted. Only gradually did it all come back, culminating in that eternal, 20 mph, lay-by-crawling drive, and our arrival five hours before, stumbling up the streaming hillside to the bothy. Dreamily, I luxuriated in the knowledge that we really were dry and warm.

A wet cold had been the dominant sensation all day. The sploshing, boot-sucking walk up through the peat from the distillery at midday had been normal – the wet feet part, anyway. It was normal, too, that the back of my shirt should be soaked with sweat from the sack, even though the forecast had been for a low freezing level. But the stance at the foot of the first pitch beneath overhanging rock which perpetrated a myriad drips that did not quite add up to a waterfall, seemed out of place on a Scottish winter climb where, as all the best books tell you, weather of arctic ferocity can be expected. I had a waterproof jacket, but that nasty clammy feeling was soon advertising itself around my neck, working its way insidiously downwards, and my breeches drank up the moisture like thirsty cacti.

But if I was damp on the stance, I wasn’t going to become any drier by climbing. I was safely to one side of the spindrift cascades that were being flushed almost incessantly down the gully: Geoff was right under them, and every so often he would disappear completely. Then, the two ropes vanishing into mobile whiteness were the only assurance that I was not entirely alone. I was reminded of that wet day a fortnight previously, when we had walked as far as the CIC intending to do this climb, thought better of it, and done battle with a rainy Clachaig Gully instead. Not that I was watching closely, for chunks of ice, large and small, and some very large, were peeling off the rock above and all around, rattling like castanets on our helmets, and it was asking for trouble to look up. They weren’t as lethal as stones, but the whirring and whining and banging kept me in a state of expectant, hunched-up tension. But then, I was not climbing.

When Geoff had traversed left across a steep wall and disappeared back right over a bulge, and it was my turn to climb, I discovered that I no longer had time to worry about the lumps of ice. When the big flows came, I could only take a deep breath, keep my head down and cling on for dear life; and when the deluge eased, the sleeves of my jacket would be filled with snow, because it doesn’t have storm-cuffs. I would look up quickly to spot the next few moves, only to find that snow had piled up behind my glasses and I was blind. I was shivering and uncoordinated, and my hands lacked strength to grip the hammers. No, there wasn’t time to worry about falling ice.

I was still cold when I reached Geoff. It hadn’t seeped through to him yet, and as I wrung out the dripping Dachsteins, grumbling, he said with just a hint of malice, ‘This’ll warm you up.’ I glanced surreptitiously upwards, and caught a glimpse of an alarmingly vertical ice groove before the next torrent arrived. ‘We must be crazy,’ I remarked, and started climbing. Perhaps we were, perhaps we should have abseiled off. The climb was manifestly ‘out of condition’ and we hadn’t started it till 2.30 p.m. But it’s good to be crazy sometimes. When I lose the urge occasionally to flout the rules, to laugh in the face of the pundits, I shall know that mental middle age has set in and it is time to be measured for my coffin. Besides, now that I was leading, and all energy and attention were about to be absorbed to the exclusion of wet and cold and mere physical sensation, retreat was the last thing on my mind.

Technically, the pitch was hard, but easier than it looked, because often it was possible to bridge and not many moves were properly out of balance. Just as well, since it was like climbing Mr Whippy ice cream. Only occasionally did the hammer picks bite in securely, and since I could have waited all day for the spindrift to stop, most of the time I had no idea where I was placing hands and feet. Once, the snow gave way beneath me, and, as the weight came on my arms, the hammer picks sliced out. Even as I registered that I was falling off, both feet relocked into a bridging position two feet lower down.

Normally, I suppose, I would have been left quivering with fright. But the bombardment of ice and near-suffocation in rushing drift rendered thought impossible and I was quite unmoved. Geoff hadn’t noticed – only the blue top of his crash-hat was visible below – and I reflected that ‘what the eye don’t see the heart don’t grieve over’. Banging in an ice peg, more because it seemed the right thing to do than because I believed in it, I moved up again, and before long was ensconced in a little bay where I could rest and place a proper peg runner.

Above was a steep chimney but it seemed straightforward by comparison, and a chimneying position, with immovable rock to brace my back against, felt deliciously safe. The notorious final pitch was rearing up ahead now, and hoping to belay on rock at the foot of it, I started up another, easier-angled chimney. Halfway up, however, the rope came tight and I had to search for a belay. On ice you either climb a steep pitch quickly or you fall off: it is the quest for protection that takes time. It took me longer to find a crack that would accept half an inch of inverted blade than to climb the pitch, and though voices stood no chance against the continual hurly-burly of the snow, I was conscious of misery down below. Finally I was tied on and, wedging myself into the chimney, yanked the rope for Geoff to come.

I was a long time in that position, because Geoff knackered himself taking out the ice peg and had to be lowered down for a rest. It was sleeting wetly and there wasn’t much to look at in the confines of the chimney. In such a situation, between bouts of shivering, one cannot help but ponder. I thought back to that perfect weekend earlier in the winter, when there had been queues for all the famous gullies, and from high on Observatory Buttress I had counted sixteen climbers clustered on the Great Tower. It had been a marvellous weekend of firm snow and brilliant sunshine, yet anticlimax had hovered over it. The summit of the Ben had been as populous as the top of Matlock High Tor on a summer’s afternoon. Somehow, it just wasn’t winter climbing. This was less enjoyable; in fact, I can’t pretend that I enjoyed a single moment of the day, in the way that one consciously savours sunny stances and warm rock, or eating steak and chips. But so what? What mattered was that the door of the CIC was locked in silent condemnation and we had the mountain to ourselves. Despite clothes that clung as though I had fallen into a swimming pool, and teeth that chattered like a pneumatic drill, I was glad to be there. That sounds like bullshit, I know. I can only insist that it was true. Admittedly, morale reached an all-time low when, after an hour, Geoff was still on the stance below. I even went so far as to suggest an abseil, but a timely gust of wind blew the words to the oblivion they deserved, and almost immediately the rope started coming in again.

Finally Geoff arrived, looking as uncomfortable as I felt, with pendulous drips on eyebrows and nose, but stoical as ever. His hands were still very cold, so I led on. The final pitch looked ferociously steep, and by the time I was forty feet from the stance and a nut runner had lifted out, confidence demanded a couple of ice screws. The top one popped out when I tested it, but there didn’t seem to be any firmer ice, so I pushed it back in and pretended not to notice. In fact, this pitch also proved bridgeable, and it was legs rather than arms that could do the work; otherwise, handholds might have been necessary, as the hammer picks just weren’t biting. Unexpectedly soon I reached the top, emerging to a blessed region where spindrift flowed past my feet instead of over my head. Above, the gully lay back at a comfortable angle for 200 feet or so, before the mist gobbled it up. I felt like yodelling, but my mouth was too dry, so I simply grinned to myself, and then at myself, and was happy.

As usual, the belay was poor, but Geoff didn’t come on to the rope, and soon we were moving together up into the gathering gloom, wondering if we could be off the mountain before dark. We had forgotten the cornice. If we had been sensible Geoff would have buried his dead man just below it and I could have climbed it in relative safety. But we were both tired, and when I told him not to bother with a belay, he took me at my word and stayed where he was, 100 feet lower. The cornice wasn’t that big, but the snow was rotten, and twice I was left dangling from a horizontally embedded axe. The second time, my arms felt as though they couldn’t take much more. It was no time to worry about margins of safety. Burying one arm in the snow and holding my breath lest the footholds collapse again, I cautiously withdrew the axe and slashed at the lip until I could reach over and tap the axe vertically downwards. Seizing it in both hands, I threw one leg over the top and rolled sideways on to the plateau. We were up.

However, the saga was by no means over. The Ben was...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 27.11.2017 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Briefe / Tagebücher | |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Freizeit / Hobby ► Sammeln / Sammlerkataloge | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport | |

| Reisen ► Reiseführer | |

| Schlagworte | Adventure • Alps • Ansel Adams • Antarctica • Antartic Peninsula • bad weather • British Columbia • Cambridge • Canada • Carneddau • Chamonix • climb book • Climbing • climbing book • conservation • Everest • expeditions • Explore • Frank Smyth • Frank Smythe • Hills • Himalayas • H.W. Tilman • HW Tilman • Hymalayas • Karakoram • Kulu • Les Droites • Lhatoo Dorjee • Longstaff • Meade • modern expeditions • Mountaineering • mountaineering book • Mountains • Nature • Nepal • New Zealand • North face • North Wales • North-Wales • Peak • Peninsula • Rob Colister • Rob Collister • R. S. Thomas • R.S. Thomas • RS Thomas • Running • Self-Sufficiency • Shipton • Skiing • ski tours • ski-tours • skitours • Snowdonia • solo climbing • summit • Thoreau • Tilman • Vancouver Island • Verbier • W.A.B. Coolidge • WAB Coolidge • Wales • Welsh hills • Wilderness • wild lands • Zermatt |

| ISBN-10 | 1-911342-78-9 / 1911342789 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-911342-78-6 / 9781911342786 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 9,4 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich