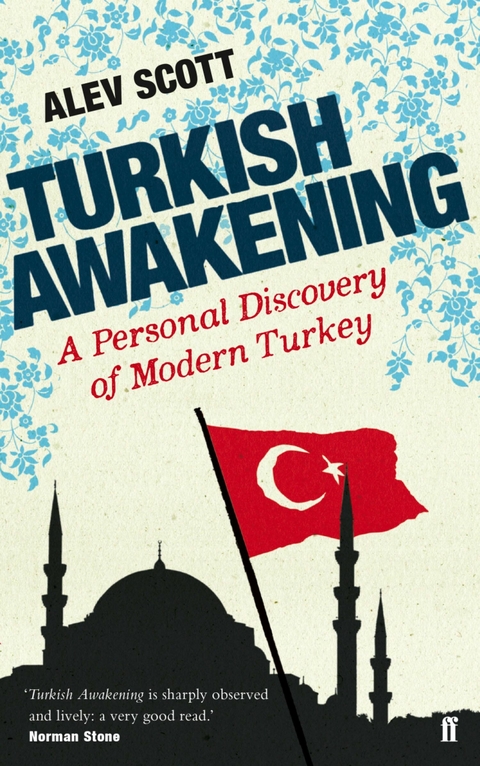

Turkish Awakening (eBook)

336 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-29659-0 (ISBN)

Alev Scott was born in London in 1987 to a Turkish mother and a British father. She was educated at North London Collegiate School and New College, Oxford, where she studied Classics. After graduating in 2009, she worked in London as an assistant director in theatre and opera before moving to Istanbul in January 2011, where she taught Latin at the Bosphorus University. She now works as a freelance journalist for the British press

Born in London to a Turkish mother and British father, Alev Scott moved to Istanbul to discover what it means to be Turkish in a country going through rapid political and social change, with an extraordinary past still linked to Mustafa Kemal Ataturk and an ever more surprising present under the leadership of Recep Tayyip Erdogan. From the European buzz of modern-day Constantinople to the Arabic-speaking towns of the south-east, Turkish Awakening investigates mass migration, urbanisation and economics in a country moving swiftly towards a new position on the world stage. This is the story of discovering a complex country from the outside-in, a candid account of overturned preconceptions and fresh understanding. Relating wide-ranging interviews and colourful personal experience, the author charts the evolving course of a country bursting with surprises - none more dramatic than the unexpected political protests of 2013 in Taksim Square, which have brought to light the emerging demands of a newly awakened Turkish people. Mass migration, urbanisation and a growing awareness of human rights have changed the social, economic and physical landscapes of a powerful country, and the 2013 protests were just one indication of the changes afoot in today's Turkey. Threatened as it is by recent developments in Syria and Iraq and the approaching danger of ISIS. Encompassing topics as varied as Aegean camel wrestling, transgender prostitution, politicised soap operas and riot tourism, this is a revelatory, at times humorous, at times moving, portrait of a country which is coming of age.

Alev Scott was born in London in 1987 to a Turkish mother and a British father, and educated at North London Collegiate School and New College, Oxford, where she studied Classics. After graduating in 2009, she worked in London as an assistant director in theatre and opera before moving to Istanbul in January 2011, where she now works as a freelance journalist for the British press.

The Naïve Newcomer to Turkey is best represented as a passenger in a yellow taxi cab, lost in the chaos of Istanbul. In the first months after my arrival, I fitted this tableau perfectly. Picture the scene: I am engaged in a highly animated, imperfectly understood exchange with a moustachioed man driving at speed through winding back streets. My attention is divided between the passing cityscape, a partially obscured meter and the rapid stream of Turkish coming from a man who expresses his emotions on the accelerator and brake pedals. My fear of death by dangerous driving has long since been anaesthetised: we are deep in a discussion about whether the extortionate price of petrol in this country is the result of secret machinations between Israel and France. Dull scepticism is rejected out of hand, so I suggest Iran as a third contender in the conspiracy and have the satisfaction of commanding his immediate attention.

Ever since I got my Turkish good enough for a basic conversation, I have made an effort to talk to taxi drivers. Most have been extremely friendly, a few suspicious of an inexplicably talkative girl. I have conversed with frustrated poets, acute sociopolitical commentators and gifted comedians. Many have just been homesick family men from some distant part of Turkey – often the Black Sea. People are drawn to Istanbul from all over the country, so it is the best possible place to meet the gamut of national stereotypes. If you get a genuine Istanbullu taxi driver (which is relatively rare), he is guaranteed to lecture you about the good old days before country folk swamped the city with their religious nonsense and bad driving.

From an initially dispiriting level of miscommunication in the Turkish language, I gained confidence as the kilometres racked up and emerged as a kind of reverse Eliza Doolittle, using accented slang that has profoundly shocked my Turkish mother. ‘My God, you sound like a taxi driver!’

Talking to taxi drivers taught me as much about Turkish modes of behaviour as it did language skills. Lesson number one was that Turks can be extremely open, with friends and strangers alike, leading to some rather uncomfortable situations for the uninitiated, uptight English passenger. I have only just graduated from this state. Once, I hailed a taxi outside the Bosphorus University where I had been teaching all day. I slumped in the back, exhausted, and gave the driver brief directions.

‘Urgh, have you been eating garlic?’ came the unexpected response.

I admitted I had, for lunch, some hours earlier.

‘Well, you really stink. Don’t take it personally, I happen to like garlic, but you might want to avoid confined spaces for a while.’ The driver was being so spectacularly rude that I assumed I had not understood his thick Anatolian accent correctly. To dispel my doubts, he wound down all the windows despite the December chill and kindly handed me a stick of chewing gum as a refreshing reminder of Turkish frankness.

An upside of this disconcerting national trait is that people don’t beat about the bush, which saves time and can be extremely helpful. The taxi driver with refined nasal sensibilities might not have had the most polished of manners, but he was not being unkind. I love the down-to-earth attitude of Turks, and have consistently been impressed by their spontaneous kindness – little gifts and offers of help, which by British standards seem almost sinister. It is a quality found in many Middle Eastern countries, although sadly sometimes a difference in sex limits meaningful encounters. I often feel short-changed in this respect. In the local food bazaar, the religious cheese-seller is all smiles with my boyfriend, chatting away, but he won’t even look me in the eye, let alone speak to me. My involvement in the conversation is confined to eavesdropping and looking meek. Once the cheery cheese man gave my boyfriend a piece of halva, a sesame-based sweet, to try; my piece was carefully placed on the counter in front of me, as though for a passing bird. I do not resent the man – he is clearly generous and warm – and in fact, he is being as respectful as he knows how by not looking at me, the ‘property’ of another man. It is how he has been brought up. My quarrel is not with him but with the kind of Islamic fundamentalism that prevents and perverts well-meaning human connection. It is a shame – it would be nice to share my own jokes with the cheese man rather than living vicariously through my boyfriend, but I know it will never happen. Apparently, he rather sweetly asks after my health when I am not there.

Far more than elsewhere, I find that the way I am perceived by others in Turkey depends on how I am dressed, who I am with and where I am. In the most glamorous areas of Istanbul, like Nişantaşı, Bebek or Etiler, I am noticeably shabby, uncoiffed, probably taken to be a student hippy or worse. In downtown Istanbul, in poor neighbourhoods full of migrants, like Çatma Mescit (full of families from Sivas, central Anatolia) or Kadın Pazarı (Kurds from Van and Diyarbakır), the buses are packed, taxis empty and I am definitely a ‘White Turk’ (or what in Regency England would have been called ‘Quality’). On a recent trip there, I started to chat with my driver, who seemed pleased to share his views on the world. Suddenly, a car swerved in front of him to switch lanes.

‘Kürt! [Kurd!]’ he yelled, shaking a fist.

From then on, every instance of bad driving was accredited to Kurdish origin. In the midst of my shock, I was interested to know whether the driver was using the insult jokingly or unthinkingly, as one might say ‘bastard’, or whether he actually had a thing about Kurds. It turned out he did – he proceeded to relate a recent news story about a Kurd who had married an English lady, started a property development project with her somewhere in Antalya, and then made off with several thousand euros. The possibility of a Turk, American or Samoan doing exactly the same thing had clearly not occurred to this particularly irascible taxi driver. The force of his prejudice was such that I despaired at the thought of trying to reason with him, and what really disturbed me was the realisation that he had judged me to be someone who was likely to share his views, being fairly well off and clearly not a Kurd.

The status and perception of Kurds among Turks is a very complicated issue, which I address later, but I brought up this example to demonstrate the fearlessness with which (male) Turks share controversial views. In England, anyone with a private prejudice against some ethnic group will probably think twice before voicing it among strangers. There is a notion that expressing such views is not really the done thing, even if they are strongly held. I have often felt in Turkey that I have unfettered access to people’s thoughts, which has been very educational.

Taking taxis in Istanbul is a form of instructive entertainment; I cannot count the number of contradictory conspiracy theories I have heard so far. I once had a driver who held forth on the subject of the disgraceful number of covered women in Istanbul – this man was a dyed-in-the-wool secularist, that much was obvious. I listened with half an ear until he asked me a direct question: ‘Do you know what they do?’

Who?

‘These covered women. All shut up at home together, all day. Do you have any idea what they’re up to?’

No.

‘Grup seks!’

Yes, group sex. Lesbian orgies, that was the vision this man had of secret goings-on in the most religious districts of Istanbul. Even in my wildest dreams I could not have envisaged, say, a paranoid BNP supporter in the depths of the Midlands making such a bold and imaginative Islamophobic accusation, but here was a Turk calmly stating what he regarded as the plain truth. Battling to keep a straight face, I suggested that this was the reason their birth rate was so high. Nodding gravely, he was about to continue his polemic when the intricacies of human biology filtered through the fog, and he shot me a frown as if to say: ‘Be serious!’

The taxi business is a very good example of the lingering Byzantine practices still going strong in Turkey. Behind the ostensibly upright system in place, favours are bestowed, scores are settled, and nothing is straightforward. Driving a taxi in Istanbul, in particular, seems to me to be a great test of character, for the following reasons: Istanbul taxi licences are sold at supposedly public auctions, but these are widely reputed to be controlled by a mafia who make sure the right people get the licences, and then sell them on at profit. Subsequently, taxi owners pay (or likely borrow) around seven hundred thousand lira (£250,000) just for their unfairly expensive licence, which is a lot of money by Istanbul standards. Most owners then rent out their taxis for a hundred lira (£35) per half day. This is where the test of character comes in – some drivers choose to earn this money back honestly, with the meter and the shortest route. In the heart of tourist land, however, you will find specialist taxi drivers who quadruple the distance actually needed to drive from, say, a hotel near the Blue Mosque to Taksim Square, often neglecting to put the meter on, and sometimes even crossing over to the Asian side and back again.

I have little sympathy for these vultures, but I can understand the mentality of those who resent the system as it stands and try to buck it in an illegal but relatively honest way: unlicensed taxis. I must first make clear that all this information was taken from the horse’s mouth, from...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 4.3.2014 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Reisen ► Reiseberichte |

| Reisen ► Reiseführer ► Asien | |

| Schlagworte | Istanbul orhan pamuk • mini break • museum of innocence • Recep Tayyip Erdogan • Taksim Square • Turkey • Turkish |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-29659-9 / 0571296599 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-29659-0 / 9780571296590 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 1,1 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich