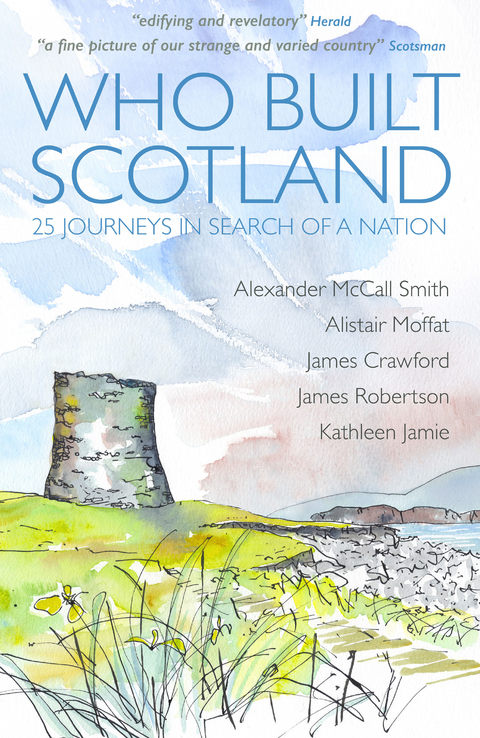

Who Built Scotland (eBook)

432 Seiten

Historic Environment Scotland (Verlag)

978-1-84917-245-5 (ISBN)

'a fine picture of our strange and varied country' Scotsman

'edifying and revelatory' Herald

'an epic love story to Scotland' Courier

'by turns inspiring and fascinating ... a book that gives context to the Scotland we see around us today' Undiscovered Scotland

'a fascinating alternative take on the country's social, political and cultural histories' Scottish Field *****

Kathleen Jamie, Alexander McCall Smith, Alistair Moffat, James Robertson and James Crawford travel across the country to tell the story of the nation, from abandoned islands and lonely glens to the heart of our modern cities. Whether visiting Shetland's Mousa Broch at midsummer, following in the footsteps of pilgrims to Iona Abbey, joining the tourist bustle at Edinburgh Castle, scaling the Forth Bridge or staying in an off-the-grid eco-bothy, the authors unravel the stories of the places, people and passions that have had an enduring impact on the landscape and character of Scotland.

Alexander McCall Smith is the author of over 80 books, including

the world-famous No. 1 Ladies' Detective Agency series and the

Scotland Street novels.

Alistair Moffat is an award-winning author of history books including Scotland: A History from Earliest Times and The Great Tapestry of Scotland.

James Crawford is the Saltire-nominated author of Fallen Glory and the presenter of the landmark BBC TV series Scotland from the Sky.

James Robertson is the Booker-longlisted author of highly acclaimed novels including And the Land Lay Still, Joseph Knight and The Testament of Gideon Mack.

Kathleen Jamie is a Saltire and Costa-winning writer of poetry and non-fiction, including The Bonniest Companie and the critically acclaimed essay collections Sightlines and Findings.

1

Signs and Traces

Kathleen Jamie

Geldie Burn, 8000 BC

In the beginning was a hearth, a gathering round the fire.

In the beginning was shelter, hides stretched over wood, with water nearby.

In the beginning was the land, not long emerged from the ice, seashores, rivers, glens and watersheds. Birch and hazel woods, the open hill.

In the beginning was the smell of fish roasting in the cinders, of hazelnuts.

Nowadays, if you make your way to Braemar, and then to the Linn of Dee, it’s possible to park a car there under the Scots pines, and walk or cycle farther into the Mar Lodge Estate, following the upper Dee by a Land Rover track through its broad strath up to White Bridge, where the Dee and the Geldie meet.

Back then, 8,000 years ago, you lived with stone and wood. With animals, birds and fish. With the seasons and the weather, with one another. You moved around the country: a season here, a gathering there. Some places were familiar; you came over and again, took what you needed. Intimately your hands knew wood, stone, bone, hide, gut, grass, bark, sinew, antler.

The bridge crosses the Dee, which would otherwise be dangerous in spate. You pass remnants of native pine wood and more modern plantations; a few ruined blackhouses. Signs direct you toward the high passes, the fabled names of the Cairngorms: the Lairig Ghru. The hills are almost free of snow. The sky is high and clear; today, white clouds are travelling eastward.

It wasn’t enough to say ‘bone’. Which bone? Scapula or knuckle? Which species of animal, at what age? Likewise grass. What kind was best for weaving hoods, which for fish baskets?

You knew these things. You knew things we’d still recognise now, in our hearts: the smell of wood smoke, faces by firelight. The stars at night. The turning seasons. A coming and going. Voices. Tasks to be done.

A day in early summer then was just as long and as full of bright promise.

At Chest of Dee you can follow that river higher toward its source. There is a narrow part where the water, blue and aquamarine, surges between rocks so strongly it purls backward on itself. A place of recreation and solitude, haunt of the long-distance hillwalker and naturalist.

Potentially dangerous. The hills stand guard. In the clear meltwater of the pool at the waterfall, a single fish inhabits its own world.

At the confluence of two rivers, on a flat shingly riverbank. The water is fast and clear – almost greenish. It’s meltwater falling through a tight linn, draining the snowfields higher in the mountains. Perhaps there are sparse stands of birch, hazel, even pine to feed the fires. There is a camp. Tents of hide, windbreaks of woven willow. Morning smoke. Voices. Work to be done. Around the tents are drying racks for fish or meat, frames to stretch skins.

When you arrived there were the traces of the last time you were here – bits of stone, a midden, dark ashy patches where the fires were lit – a familiarity. You’re here for a reason, following something maybe, a herd of animals that gather at this time of year. Or a certain wood, or a certain kind of stone. You have followed a river well inland, almost to its source.

The river which meets the Dee here is the Geldie. ‘Geldie’ is an old name meaning clear, white, pure. The track follows the river as the Geldie trends eastward. Today, 25 blackcock were gathered at their lek, an adder basked on the path where the Bynack Burn joined the Geldie.

The path rises onto heather, then narrows to a walking trail.

The river is below on your left, meandering and looping because the little strath is level; the hills on the south side are even, glaciated, heather covered. There are no trees whatsoever. On the opposite bank stand the ruins of Geldie Lodge, a nineteenth century shooting lodge; a brief intervention in the landscape, in the long scheme of things.

You know fine well that if you follow one of the rivers, it will take you higher into the hills. You were first taken there as a youngster – it was an adventure. After some hours’ walk you will turn westward into a higher, lightly wooded valley, with a marshy floor. Perhaps there are deer up there, grazing quietly, maybe even reindeer on the high slopes. Perhaps the reindeer are already gone, they have become a story the elders tell.

However, you’ve left the main camp by the waterfall and crossed the major river. Alone, or in a small gang. You follow the lesser river, keeping to its northern bank and head into the hills. There’s a place you favour upstream, a good morning’s walk away, where you reckon you’ll stop for the night. Though it’s on a small ridge, it’s sheltered among spare trees. The valley it looks out upon is sedgy, with sparse birch and hazel trees. The gentle hills are green.

It was here, at about 1,500 feet, where the path crosses Caonachan Ruadha (the wee red burn) that some workers repairing the eroding footpath discovered under the peat a number of tiny flint artefacts. They saw them with a sharp eye; a hunter-gatherer’s eye.

The flints comprised what the archaeologists call a ‘lithic scatter’. Tiny blades, not the length of your thumbnail, flakes and off-cuts of flint and rhyolite. They lay strewn in such a way that suggested they had littered the ground around a fire within a tent of some kind. A small camp, no more than two or three people on a high route through the hills, among trees, perhaps for some special function. That was before the peat came and covered them.

Another half day’s march would take you to the top of the glen. The hills, still snow-wreathed, appear to close the glen but you know there are routes between them. If you kept walking and managed some tricky river crossings, you’d find your way down into another separate river system, a whole different part of the country, maybe another kind of people. But tonight you stop.

What have you brought? You’ve brought some means of making fire. Hides to sleep under. Tools, knives to cut a few withies. A pouchful of nuts, pemmican of some sort. Some twigs of yew – why that? For its cleansing smoke, for tipping poison darts? Snares, which you’ll set. The pelt of a hare, still in its winter whites, makes perfect mittens, baby clothes. Perhaps bow and arrows, perhaps you’re waiting for migrating animals to file through the high pass.

You set the fire. Do you need to consider bears? To keep someone awake on bear-watch at night? Maybe you’ll see prints in the marshy mud but they won’t worry you.

The scatter of flints, a fire-scorched place, the site of what was likely a shelter. Little else is preserved in Scotland’s somewhat acidic soil. The carbon dating of the hearth gave dates of 8,000 years ago; suggesting the mountains were part of people’s range and resource from the earliest days of human settlement.

Why were they here?

At this time of year the nights are short but cold. Actually, they’re getting colder. The elders say winters are much colder than they used to be, snow and ice are lingering longer into the year. You relish the daylight, having come through a winter lit mainly by moon and firelight, or lamps of animal fat. Here in the high glen, you use the gift of daylight. You sit on stones in the gloaming by the fire re-sharpening and re-working tools: the tiny blades and flint points which are an endless labour if they are to keep their edge. A stone in either hand, you knap carefully. The chipped-off pieces lie where they fall. The flint has come with you from the coast, but there are rhyolite outcrops up here. Perhaps you’ll fetch some while you’re about it. Yours are working hands: muscular, knowledgeable.

You feed the fire. When you talk, you talk about what you’re doing, about each other, about weather-signs, animal-signs. Some daft adventure you recall. A story.

What do you call this place? Where did you say you were going when you set off, and why? Who might you meet up here, on the high track through the mountains?

There are Mesolithic sites all along the Dee, only now being discovered. At Chest of Dee, there were bigger sites, possibly longer lasting, repeatedly visited, with their hearths and lithic scatters. It may be that this little camp at Caochanan Ruadha is an outpost of those. You can sit here now under a bright sky and look westward up to where the river rises.

You might meet a lone walker passing, with his backpack, a portable shelter, some warm well-made clothes, some easy-to-carry food. When he speaks, you can tell where he comes from. He describes crossing a river, dangerously, water up to his waist. You exchange pleasantries, he walks on.

Your shadows are long as you walk away from camp to check your snares before the ravens get there first. The sky is clear, ashy pink in the west, a quarter moon already risen high. It all bodes well for the morrow, and the morrow. You lived lightly on the land for 4,000 years.

Imagine! Four thousand spring times. A million and a half days and nights. What did they build, our hunter-gatherer forebears? Nothing as yet discovered, if by ‘build’ you mean stone piled on stone. Our forebears left little trace of themselves before the transition to farming was complete. But they built a long culture, a profound knowledge communicated by...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 14.9.2017 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber |

| Reisen ► Reiseführer | |

| Geisteswissenschaften ► Geschichte ► Regional- / Ländergeschichte | |

| Technik ► Architektur | |

| Schlagworte | Architecture • buildings • History • Scotland • Travel |

| ISBN-10 | 1-84917-245-5 / 1849172455 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-84917-245-5 / 9781849172455 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Digital Rights Management: ohne DRM

Dieses eBook enthält kein DRM oder Kopierschutz. Eine Weitergabe an Dritte ist jedoch rechtlich nicht zulässig, weil Sie beim Kauf nur die Rechte an der persönlichen Nutzung erwerben.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich