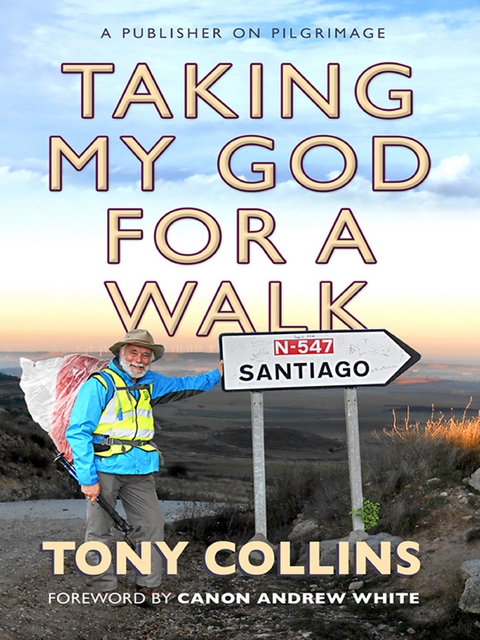

Taking My God for a Walk (eBook)

249 Seiten

Lion Hudson (Verlag)

978-0-85721-774-5 (ISBN)

St Jean Pied-de-Port

Days 1 and 2

One of the main starting points for the Camino Frances is a mountain village on the French/ Spanish border, St Jean Pied-de-Port. Fly from Stansted to Biarritz, then catch the stopping train. Stansted Airport, shiny and efficient, is a slightly unreal departure point for a journey to the medieval world. In the queue for Ryanair’s services I looked over my companions, trying to spot someone on a similar quest, notable for his noble mien, his gaze fixed on infinity. Or her eminently sensible boots.

My curiosity had a purpose. The guidebook suggested an alternative to the slow and infrequent train: a taxi straight to St Jean, economical if shared. No joy. The aircraft seemed packed with sun worshippers in search of their fix.

Standing in the autumn warmth on the Biarritz tarmac I finally spotted a fellow pilgrim, instantly recognizable by his hat and backpack. I approached, hoping to share dreams, information, and a cab.

“Nope, just going home,” he responded. An entirely British raspberry farmer with the unlikely name of Jean-Paul, he lived outside Biarritz. “But I’ve walked bits of the Camino,” he volunteered. “You see some crazy people. I met one guy pushing a shopping trolley.”

Jean-Paul was headed for the local railway station, a few miles by bus, and helpfully guided me to the right stop. As we swung through down-at-heel French suburbs I pressed him for advice. He thought. “Look up,” he offered finally. “People spend their entire journey staring at their feet. If you look up you may spot a stork. Or a vulture.”

An elegant bar dominated the station concourse. A lissom young waitress served me a lager and a sandwich au jambon.

Unmistakeable pilgrims, silent and pensive, occupied adjoining tables. I proffered the taxi idea, but no nibbles. “We want to take the slow train,” observed an Austrian girl, fluently but tartly. “It is beautiful.”

I realized uneasily that I was still on a schedule. Recognizing a small turning point sidling up, I stared at my wrist. An inveterate last-minute merchant, for years I had kept every timepiece fifteen minutes fast, all part of the security blanket. With a sense of occasion I removed my watch to correct it, and checked the station clock. By French time I was forty-five minutes slow. I could have missed my train.

As I sat there my mobile pinged. Pen had texted an Irish blessing.

May the long time sun shine upon you,

all love surround you,

and the pure light within you carry you all the way home.

“Praying for you every day,” she added. “I have you in my heart.”

On the platform at Biarritz station I joined a cheerful group. Michael, a fit young German cameraman, had walked the Camino that spring, and was now doing it all over again to make a documentary. I looked at him with increased respect, and he grinned.

“There are four stages to a pilgrimage,” he told me. “The body, the mind, the stage of love, and the stage of parting.”

The little local train finally chugged into the station, and departed again crammed with pilgrims. As we clanked up through the chestnut-wooded foothills of the Pyrenees, crossing and re-crossing an ever-faster mountain stream, I stared in disquiet at the increasingly vertical scenery and wondered if I would ever make it beyond stage one.

I enjoy entertaining French nationals with my version of their language. But while we plugged away at the gradient, pausing briefly in every tiny halt, I realized that though I had been expecting the transition to Spanish, I was unprepared for Basque. As I tried to get my tongue around one impossibly unpronounceable set of consonants after another, and saw emblazoned on every rock and wall the Basque colours of white over red, it came to me that “Spain” might be a name on a map, but to quite a lot of people on that map it does not describe their homeland. Spain is an archipelago.

Before leaving home I had registered myself with the London-based Confraternity of St James,9 and received their rather lurid mustard-yellow Pilgrim’s Record, whose blank pages would serve as my credencial. With it came their regular “Bulletin”, a slightly alarming amalgam of stories, slivers of history, memories, and reports which all carried, to my editor’s nostrils, a scent of deepest conviction, and left me slightly nervous: in this company, was I a flake? In the enthusiastic world of the Confraternity, it seemed, you could not dabble. But what did it take to become a real pilgrim?

St Jean Pied-de-Port – St John’s at the Foot of the Pass – exists to serve the pilgrim trade, each ancient house on the winding central street offering budget accommodation or your choice of authentic pilgrim’s staff. St Jean forms the last stop on the French side of the border for pilgrims coming from Paris, Vézelay or Le Puy before the tough mountain crossing. As I afterwards discovered, the original town (Saint-Jean-le-Vieux) was obliterated by Richard the Lionheart in 1177: tactless, to say the least, and easily misunderstood, but today the British euro seemed welcome.

At the modest station we alighted en masse into the setting sun, stretching and muttering. The train emptied completely: this was the end of the line.

I wrestled my pack onto my shoulders and followed the stream of travellers up the steep road, through the gate in the high defensive walls,10 and into the core of the town, stumbling over the cobbled streets and admiring the ancient houses of pink and grey stone, old when the Revolution came. I eventually located the Pilgrim Centre. It was after eight o’clock – I had missed the Monday market, when sheep and cattle are driven into the little town – but the centre was still crowded, with practical ladies ranged behind tables.

I waited in line, and proffered my credencial. My interviewer examined this curiously: the first such response of many. It later became clear that while the Confraternity (a British institution) is well established, Brits are comparatively rare beasts on the Way, accounting for less than 2 per cent of the whole.11 Fewer still are members of the Confraternity. My all-too-visible booklet would provoke comment all the way to Santiago.

I dutifully received some instructions, a sheet of emergency numbers, warnings about bad weather, and my first sello or stamp, with a green representation of a medieval traveller.

Every hostel and bar has its own stamp: it is possible to collect hundreds, each one different and some a little jolt of beauty. These are an indispensable part of the Camino, and enable you to demonstrate that you have visited the locations you claim (though they are helpfully silent should the flagging pilgrim opt for a taxi). The credencial is your passport to an inexpensive, dry, safe lodging: it shows you are playing the game. Most credencials are not my gaudy affair, but simple cards, folded concertina-wise, and by journey’s end dappled with overlapping sellos, a memento no shop can supply, and ideal for framing.

It will not spoil your enjoyment of the film The Way12 if I explain that it starts with a death: a young man is caught in a violent storm as he crosses the Pyrenees, and perishes. The path over the pass, as I discovered the following day, is marked by snow posts, and near the peak, shortly before the Spanish border, stands a mountain hut for the use of travellers.

However, there are two options. In bad weather, or if you are inexperienced, John Brierley13 counsels, take the easier but less scenic and more populated Valcarlos route, which stays closer to the main road. The name Valcarlos derives from the emperor Charlemagne, who chose that route in the eighth century during his campaigns against the Moors.

Chicken to the core, I decided Charlemagne probably knew his stuff.

That first night, in the single hostel I had booked, two Portuguese cyclists, both fluent in English, invited me to share their meal. It was a hint of frequent generosity to come. Cyclists have a hard time on the Camino, they informed me rather wryly over pasta and beans: walkers think they are cheating. However, the namby-pamby Valcarlos option was not for my friends: they were headed for the obviously more noble Route Napoléon, so called because the great Bonaparte preferred it as a means of getting his troops in and out of Spain during the Peninsular War. Brierley adds that medieval pilgrims also chose this higher option because it avoided the bandits who haunted the tree-lined lower route. There are spectacular views, he observes helpfully, and fewer cars. The Route Napoléon reaches 1,450 metres, one of the highest points on the journey, and incidentally higher than the peak of Ben Nevis. The first stage covers 15 miles.

So: more ups, followed by precipitant downs, less shade, and lots of rocks. What was wrong with this picture?

In the battle of the emperors, serious pilgrims evidently followed Napoleon. I sighed inwardly.

Breakfast was hot and fragrant French bread, fetched fresh from the bakery by our cheerful host, struggling up his narrow stairs with a vast armful of golden loaves.

I headed downhill into the grey dawn, in the wake of a trickle of other pilgrims. At the far...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 17.6.2016 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Krimi / Thriller / Horror | |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Reisen ► Reiseberichte | |

| Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Kirchengeschichte | |

| Religion / Theologie ► Christentum ► Moraltheologie / Sozialethik | |

| ISBN-10 | 0-85721-774-7 / 0857217747 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-85721-774-5 / 9780857217745 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich