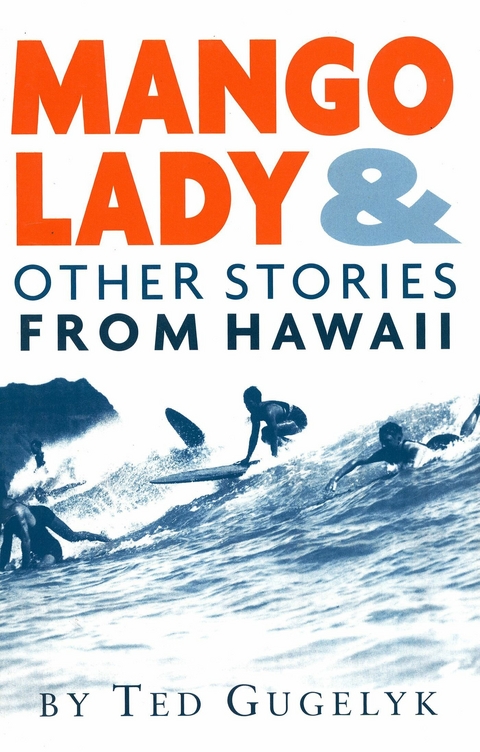

Mango Lady & Other Stories from Hawaii (eBook)

102 Seiten

First Edition Design Publishing (Verlag)

978-1-62287-240-4 (ISBN)

Mango Lady & Other Stories from Hawaii takes the reader on a journey not unlike a long ride across the face of a giant wave, full of unexpected turns and surprises, weaving together memories, fantasies, and personalities that stretch from long ago Hawaii to modern day Vietnam. Through all of them is the connecting spirit of the Islands, its special mana, its people, its surf, bringing times past into the present in a special, intimate way. There is Mango Lady, who lived in Waikiki since childhood, watching her ancient preoccupations become irrelevant in the new bustle of development. There is "e;The Man to Whom Surf Cam,"e; the tale of a magical Urban who never failed to attract surf. There is "e;A November Surfer,"e; an adventure of a senior surfer at remote Rabbit Island. There is "e;Hard Port,"e; an intriguing pulling together of Hawaii and Russia, when a longtime surfer visits Nakhodka in the Russian Far East, the land of his ancestors. Finally, there is the flamboyant and unsettling "e;Captain Aloha,"e; a tale of two old surfing friends from Hawaii and the horrors of the war in Vietnam, a unique portrait of psychology and culture, of friendship and passing time.

MANGO LADY

The old woman planted herself on the Waikiki road. Bent over low, her back parallel to the earth, feet set wide on legs still strong, she rooted herself there each morning, to scrape mango off the road fronting her house. She had huge mango trees. They overshadowed her little white house in Waikiki. Her husband, a Hawaiian man, was long dead. And her children, they had scattered. When her children were young, they helped pick mangoes. Climbing the huge trees, they scampered along the arching mango limbs, happily chatting like mynah birds. They had picked golden fruit for her. No mangoes fell on the road then. Then, she would give the sweet fruit away. To neighbors, tourists, friends—anybody in Waikiki. But now, the fruit dropped unpicked onto the road, to be crushed by passing cars. She did not like to see the sweet fruit crushed, pressed into the black asphalt. It made a yellow stain, and the juice would ferment in the sun. “Mango vinegar,” she called it. It attracted flies, and she liked her place neat. “So messy, the mangoes,” she lamented, “and no one like pick for kau-kau eat, like before. Before we make chutney. Then no waste nothing. ” But now, she was alone, to scrape ripe, sweet mango from the road. When a car approached, the old woman slowly shuffled aside, then returned to her place. It was a ritual. Because she liked her place neat.

I first met her in 1958, before Statehood. She had lived in Waikiki—on Paoakalani Road—for fifty years. I rented a room from her. Her house was two blocks from the beach, close to Queen’s Surf, and Waikiki was a sleepy little residential neighborhood. She knew many hotels would come soon, yet she said, “For me, no matter; soon I make (die). But the mango, they no like,” she laughed. She asked me to call her “Mrs. Chop Suey,” because, “I all mix up. Chinese, Kanaka, Portoge. Me, I get everything—except one young husband.”

I often watched her work—that is, when the surf at Waikiki was flat or when the country waves were down. Then, with nothing else to do, I watched her and I studied for my university courses, reading textbook assignments while seated in a wicker chair leaned back against one of her ancient trees. With a mischievous smile, she would look up from her scraping and ask me loudly, “Haole boy, how come no kanaka girl no catch you yet?”

Haole boy. When I first arrived the summer before on a transpacific yacht in a race from Southern California to Honolulu, she rented me one of her rooms. “Forty-five dollars one month. You pay first, then I show you house.” And she called me “haole boy.” I had already been amazed by the country-Western influence in these Islands, so I assumed she was greeting me with “Howdy,” as in Texas. But I soon found out that “haole” meant “white” (Caucasian), and later I heard it called out to me from passing cars on uncrowded Kalakaua Avenue, and out in the surf at Queen’s, and at the new surfing break created by the dredging of a new yacht harbor, the Ala Moana Bowl. By then I knew I was not being greeted by brown Texans. Yet everyone was friendly to “haole boy.”

When we grew chilled and tired from hours of wave catching, the Hawaiian surfers introduced me to hot plate lunches of curry stew and rice, red-pepper-spiced cabbage (Korean kimchee), Japanese cone sushi, and Chinese manapua, washed down with Royal Hawaiian beer. I promised to make borscht for them someday. When they learned I was Ukrainian, they no longer called me “haole”; they called me “Pushkin.” When they learned I wrote poetry, they called me “Bullshit.”

Occasionally, some of my Hawaiian friends dropped by the old woman’s place—not because I lived there, but to pick green mangoes. I had told them of her mango-scraping ritual, and they came to assist her a bit by eating a few mangoes. They also taught me to eat green unripe mango with soy sauce. “You get so much to learn, Pushkin,” they said.

One of those Hawaiian boys, Urban Lokini, also had much to learn. Wanting also to be a student-surfer, he told his Hawaiian friends he too attended the university—with myself and the other young boys, mainlanders and local Japanese. “I studying medicine,” he said, proudly. From then on, Urban assumed a serious and lofty air and carried textbooks with him to the beach. One day we took the liberty of examining his books and found they consisted of an old Collier’s Encyclopedia Index and a high-school anatomy book. Occasionally Urban would show up when the surf was very good, saying he was too busy to play. Sitting in the sand, he would study his text, stating, “I have to take my medical exam soon, you know.” Of course, he was teased unmercifully, for we all knew there was no medical school at the University of Hawaii. Later, he actually audited an introductory sociology course taught by Dr. Andrew Lind. From then on he was nicknamed “Dr. Urban-Suburban, Rural-Rustic Lokini.” I think the old woman enjoyed having us boys around.

So, sometimes after a day of surfing, we sat together eating mango, under her ancient trees, on a patch of lawn, beside the old white frame cottage, surrounded by greenery in the leisurely quiet of evening Waikiki. Around her yard ran a chicken or two, disturbing her old and sleepy dog named “Uku,” Hawaiian for “flea.” In time, surfboards began to accumulate around her yard—my friends found it easier to leave the boards close to the beach, than pack them on the roof of their 1948 Chevy, tied down with rope. They lived somewhere mauka (toward the mountains), they said, and one lived out in Ewa. I never met their families. But I knew that Kimo’s father was a fireman, Chubby’s dad a cook, but Urban’s father, he was not around. Urban seemed to live in no particular place. In time he took to sleeping at Mango Lady’s house. He told me he was “hanai”—adopted— so Mango Lady took him in as one of her own. But even then it didn’t work for Urban. He drank too much, and the old woman began to scold him for it, and Urban left. After that I saw him only occasionally, when the surf was large, always carrying his “medical books.” Urban also stopped attending the university sociology lectures. He told me, “Pushkin, I no got time for nothing no more. The doctor exams, they cuming up soon you know!”

I didn’t tell you about Red. Old, thin, brittle and mostly silent, Red. He also lived at Mango Lady’s, but in the garage, that part of it which was converted into a kind of hutch. Inside there was just enough space for his cot and dresser bureau with a cracked yellowing mirror attached. Scattered everywhere were his shaving things and empty whiskey bottles. He drank Old Granddad, and lived haphazardly, his cot crammed between the wash basin and toilet; his clutter was reflected in the mirror for all to see outside under the mango tree.

Red was a World War II veteran and former Pearl Harbor worker. He never said much, but sat with us under the mango tree, whittling. All day he whittled at a mango branch, until by evening, it was as small, thin and delicate as a clarinet reed. He sat and whittled down a new branch each day with his Navy pocket knife. Some days his hands shook badly from drinking. And the man’s skin was red and wrinkled; that’s how he got his nickname. But he was red not from the sun. He had caught a skin disease in the Pacific jungles during the war. His entire body was inflamed with white scaly peels, like skin after a bad burn, it looked. On his scarlet and peeling chest, he had “Hot” tattooed over one nipple, and “Cold” over the other.

His arms were decorated with bold black anchors and “US NAVY,” and a red Chinese dragon spitting flames was quickly lost in the hue of his inflammation. When he looked up at us, his eyes were deep blue, but running thick, watery with clear mucus.

One afternoon looking up at me he said, “The Japs are going to take Hawaii. Here I thought we killed all the little bastards at Guadalcanal.” He told me he was working at Pearl Harbor when it was bombed. He had worked ‘over-time’ that Sunday. After the attack he shipped out to the Pacific battles, to Micronesia and Melanesia. Afterwards, instead of going home to Iowa, he settled at Mango Lady’s, to carve clarinet reeds of mango wood and bemoan the steady advance of Japanese across the Pacific—this time as tourists, and businessmen. “We mowed them down like oats,” he said. “We mowed them down like a sickle mows wheat. But they’re still a-coming. I didn’t think there were many left when we got done with them. But oh man, here they come. Man—man oh man, here they come again.”

As he whittled, he shook, hunched down over his mango reed and knife. When the sun sank, Red was always the first to leave the shade of the mango tree. He grew chilled and preferred to retire early to his little nook with the warmth of whiskey and solitude memories, leaving Mango Lady to talk to Urban and me. With Red slumbering among his haunted dreams, she spoke in whispers, above the settling Waikiki night, the sounds of a gentle surf a short stroll away.

In the dark she talked of mangoes, how to make chutney, of ancient ocean voyages, of brown peoples in...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 12.12.2012 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur ► Biografien / Erfahrungsberichte |

| Literatur ► Romane / Erzählungen | |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport ► Segeln / Tauchen / Wassersport | |

| Reisen ► Bildbände | |

| ISBN-10 | 1-62287-240-1 / 1622872401 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-62287-240-4 / 9781622872404 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 1,0 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich