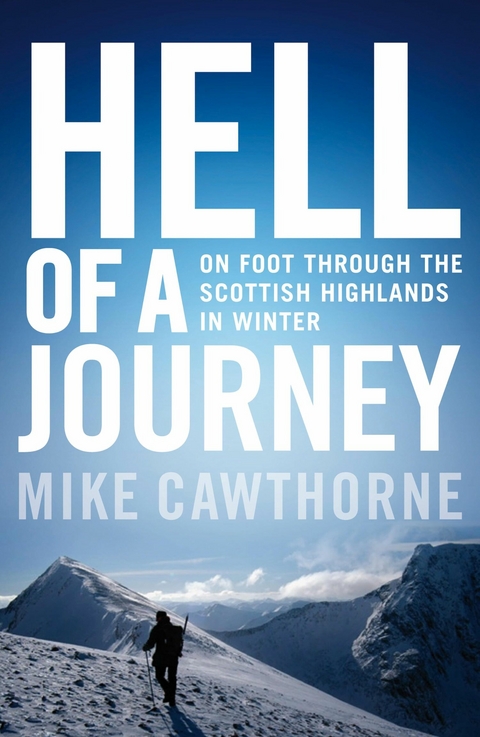

Hell of a Journey (eBook)

224 Seiten

Birlinn (Verlag)

978-0-85790-627-4 (ISBN)

Mike Cawthorne began hill-walking on Ben Nevis aged seven, and has been climbing mountains ever since. He has worked as a teacher, professional photographer and freelance journalist. He has an intimate knowledge of the Scottish Highlands, undertaking his first long-distance trek there in 1982. He lives in Inverness.

Hell of a Journey describes what is arguably the last great journey to be undertaken in Britain: the entire Scottish Highlands on foot in one winter. On one level it is a vivid and evocative account of a remarkable trek - never attempted before - on another it celebrates the uniqueness of the Highlands, the scenery and ecology of 'the last wilderness in Europe'. The challenge Mike Cawthorne set himself was to climb all 135 of Scotland's 1,000-metre peaks, which stretch in an unbroken chain through the heart of the Highlands, from Sutherland to the Eastern Cairngorms, down to Loch Lomond, and west to Glencoe. His route traversed the most spectacular landscape in Scotland, linking every portion of wilderness, and was completed in the midst of the harshest winter conditions imaginable. Acclaimed on its first publication in 2000, this edition contains an epilogue in which Mike Cawthorne reflects on his trek and wonders what has changed since he carried it out. He warns that 'wild land in Scotland has never been under greater threat'. Hell of a Journey is a reminder of what we could so easily lose forever.

Mike Cawthorne began hill-walking on Ben Nevis aged seven, and has been climbing mountains ever since. He has worked as a teacher, professional photographer and freelance journalist. He has an intimate knowledge of the Scottish Highlands, undertaking his first long-distance trek there in 1982. He lives in Inverness.

First Storm

IT WAS the middle of November, and for a mind incurably tied to an annual pattern of events—terms, exams, holidays—this time of year always meant a visit to Dovedale in the Peak District National Park. For a hundred or so adolescents it was their first experience of real countryside. They came from the grimy heart of a Midlands conurbation, that well-known area between the city centre and inner ring road, where derelict factories and poor housing exist cheek-byjowl with superstores and incinerators, and where dual carriageways rumble all night. And now, suddenly, a land of limestone towers—like minarets they seem—of arches and caves so high in the rock face they must have been chiselled out by an ancient race of giants. Here was something different, as much a culture-shock for these youngsters as a visit to a far planet. For staff as well, this honey-pot limestone gorge always seemed the highlight of the autumn calendar.

Janion, a pretty South African waitress, served up breakfast, and I did not dwell too much on where else I might have been that morning. The only guest in the dining room, my eyes wandered across the road to where ash-grey moorland piled up. This was in fact the tail-end of a mountain region whose names had been with me since childhood: Fannichs, Fisherfield, Slioch, An Teallach, ‘Whitbread Wilderness’; all places I had heard and dreamt of a decade before ever seeing them for myself. By now they seemed to have all the old familiarity of friends long-known.

Even by Highland standards the region is remote. A straight-line journey from the Aultguish west towards the sea might cover forty or so miles before crossing a metalled road or chancing upon habitation. Fortunately I had many times undertaken long, meandering treks across this mountain wilderness and felt I knew the area reasonably well.

The weather remained changeable. Last night’s forecast ominously showed a huge area of low pressure brewing in the west. Troughs and fronts would soon be queuing up to charge in from the Atlantic, and while I intended climbing only half a dozen peaks, I realised it might be a week before I made Kinlochewe.

Leaving the hotel I was saddened to discover that a new conifer plantation will soon smother the rolling inclines and stream courses of the moorland fringing the road. Its boundary fence pointed me more or less in my intended direction, eastwards up a burn, through a narrow col between low hills, across a peaty bogland, then finally to the Fannich Lodge track where I unearthed a food cache. Arrival in the Fannichs from the east is always announced by the operatic presence of An Coileachan, in particular her towering Garbh Choire Mòr, ‘Big Rough Corrie’, now brilliantly spotlit by a low sun against a wall of dark cloud. In an hour the sun became haloed. I expected a downpour, and soon got it.

The rain, when it fell, came with a monsoon-like intensity, quickly finding ways through my Gore-Tex armoury, streaming down my face, seeping inside my cuffs. Fannich Lodge—I knew from past visits—was only four miles from a place where I might stop for the night, by a ruined cottage. But, as ever, memory had shortened those last miles. I had forgotten the twists and turns, the sudden inclines, how the track climbs frustratingly into the dark of an old plantation when reason suggests it should be following the lochside. Emerging into the open again my spirits soared: the sky suddenly cleared, the rain became a spray of silver drops. Warm light the colour of hay bathed the hills; pine needles on the trees glittered like glass, and Slioch sprouted through a gap in the hills freshly rinsed and hung out to dry.

Expectantly I rounded the final bend. A roofless burnt-out shell of a house came into view. Grass and moss had got a foothold around the old fireplace, tiny roots loosening the cement and adding, along with the weather, to the relentless attrition of the standing walls. In another decade they will have likely collapsed. Just then, in the ebbing light, it was impossible to associate this ruin with my first and finest recollection of these mountains.

Perhaps because they always seem fresh and vibrant, youthful impressions tend to be the most enduring. A few days before Hogmanay two of us had come this way on our very first winter foray. Train times and hours of daylight had not been in harmony, and we found ourselves walking into darkness, harried the last few miles by bruising snow showers. We caught the resinous woodsmoke hours before a house took shape from the night. As we approached the porch, boisterous voices and a sudden outburst of manic laughter came from inside. In the gloomy, smoke-choked room our eyes watered painfully as we squinted to see the source of all the commotion. A small, animated group was huddled around the fire. The great bearded one feeding the flames with a monster log turned and grinned, ‘Welcome to the Nest of Fannich’.

Subsequent days I remember as much for the manifold characters, their stories and songs which filled the long evenings and—for us—opened up new worlds, as for the gales and blizzards which continually lashed the hills outside. One night some years later we had come over the pass from the north and, in disbelief, found a scene of devastation: the Nest had been gutted by fire. It felt as though an old friend had died. I nearly wept.

With the demise of the Nest, the west end of Loch Fannich had become an even lonelier place. I’d not been back in eight years. Close by was an outhouse, probably a stable for estate ponies, and although doorless, it provided adequate shelter. I fashioned a window with a piece of plastic and threw straw into the corner. Later, when I was snug inside my sleeping bag with a scalding mug of tea, there was a modicum of cheerfulness about the place.

A southerly gale sprang up in the early hours, and from then on the booming of the wind allowed only for a fitful sleep. By morning it had churned the surface of Loch Fannich into a mass of white streaks, while inside, eddies of wind left straw and dust on my breakfast things. With the high summits effectively stormbound, the Fannichs would have to wait. I might have stayed put, climbing my mountains from this base tomorrow, but the dung-covered floor and general grubbiness was incentive enough to push northwards, seven miles over an exposed bealach, to seek the shepherd’s cottage beyond Loch a’ Bhraoin.

It was a wild and exciting crossing. Violent gusts threatened to topple me at the height of the pass and confirmed my wisdom in staying off the tops. The cottage was a fine refuge. No sooner had I settled with a brew when outside came the grinding of a low-geared vehicle, growing ever louder until it drew up outside the front door.

Through the window I saw two men in combat-style clothing with blood on their jackets. The blood was from three or four freshly killed hinds which lay slumped on the back of the all-terrain Argocat. Despite appearances they had a friendly, genial manner, expressing surprise at finding a walker out in such conditions. The older one said the estate would be closing the cottage due to continued vandalism, muttering something about ‘Duke of Edinburgh louts’. I was suddenly aware of the graffiti on the back wall, much of it innocuous, but there were also obscene drawings of the kind you might find in a public lavatory. Some wood panelling had been ripped out, probably for firewood. To be fair, the lodging had been badly neglected by its estate owners. The wooden mantelpiece around the fireplace, held to the wall by a length of string, was about to collapse, while the front door was only just secured by some folded wire. The men gone, I rolled a stone to make it fast.

Some birch wood I had collected by the loch shore gave an excellent fire. Outside, the wind was as fierce as ever: great sobbing gusts that hammered at the door like an angry mob, knocking grit down the chimney and even threatening to put in the windows.

Next day the wind appeared to have moderated a little, but this perception later proved to be entirely wrong. It was on this morning that I realised fully the stark challenge of the coming months. Any other trip and I would have stayed low, perhaps crept along the glen to the next bothy, or remained here in this one, head buried in a good book, happily oblivious to the hostile world outside. But I had run out of options. There were neither supplies nor time left to delay an assault.

From the south shore of Loch a’ Bhraoin I struck up for the long sweeping spur which would lead me to my first top, Sgurr Bhreac. Clouds were streaming across the summits like snow plumes. By creeping up the lee side of the crest it was just possible to avoid the worst gusts. However protection ran out at the tiny col a little below the summit where, as always, the most extreme gusts are found. The wind raged through the gap unchecked, freezing me rigid, knocking me momentarily to my knees. Picking myself up I clambered a few metres over some wet rocks to a small cairn, shaken and troubled by the violence of it all.

In my desperation to descend I blundered down the wrong ridge, heading north instead of east. A dangerous traverse through craggy terrain rectified the error, and in less than an hour I was at the pass I had crossed the day before. Despite a number of visits I had forgotten the scale of these mountains. On a calm, sunny day they can be daunting, but now, in the midst of a storm, they appeared gigantic and menacing, surely beyond my feeble grasp.

There was nothing in the least pleasurable about my hours on that high crest, nothing remotely sublime. It was sheer struggle; my tenure on the ridge was like a thin thread which might snap at any...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 8.3.2013 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport |

| Reisen ► Reiseberichte | |

| Reisen ► Reiseführer ► Europa | |

| ISBN-10 | 0-85790-627-5 / 0857906275 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-85790-627-4 / 9780857906274 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 3,0 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich