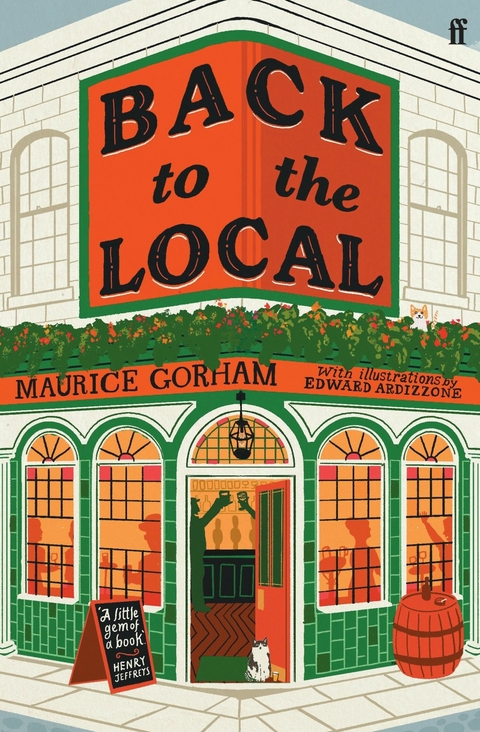

Back to the Local (eBook)

144 Seiten

Faber & Faber (Verlag)

978-0-571-28096-4 (ISBN)

Maurice Gorham (1902-1975) was an Irish journalist and broadcasting executive. In various capacities, he worked for the BBC from 1926 to 1947 when he resigned, returning to Ireland. There he resumed his broadcasting career in 1953 as the Director of Radio Eireann, a position he held until 1959. He collaborated with Edward Ardizzone on three books, The Local (reissued after the Second World War as Back to the Local- and now published by Faber Finds), Londoners and Showmen and Suckers.

One of the Financial Times' 'Best Summer Books of 2024''Probably the most delightful and evocative book ever produced on the English pub.' Slightly Foxed'Wonderful . . . a detailed study of life in London pubs.' Islington Tribune'Both a historical document and a time capsule that stands the test of time, from its charming illustrations by Gorham's collaborator, artist Edward Ardizzone, to the index of London taverns that are (largely) mostly still open.' Roisin Lanigan, Irish Independent'A book that glows like the logs on an open fire or the ruddy features of the regular ordering another glass of Burton.' Andy Miller, author of A Year of Dangerous Reading and co-host of the Backlisted podcast'A little gem of a book.' Henry Jeffreys, author of Empire of Booze and Vines in a Cold Climate'A delightful book. Perfect bedtime reading, when you get back from the pub, perhaps.' David HarsentIn this love letter to the London pub, our genial guide takes the reader through all aspects of the local hostelry as it was in the 1940s - a time of dark wood, dark corners and dark beer. Back to the Local is a fascinating nostalgic ramble around the post-war pubs of London: we are introduced to The Regulars and Barmaids Old and New; we venture into the familiar surroundings of the Saloon Lounge, Saloon Bar and Public Bar and squeeze into possibly the lesser known Jug-And-Bottle Bar, where customers queue to buy ale to drink elsewhere; we learn about 'lost' drinks such as 'The Mother-in-Law' or 'The Snort'. A truly memorable pub crawl, illustrated by the wonderfully atmospheric drawings of Edward Ardizzone. This edition includes a fold out map showing the pubs featured in the book which are still trading, plus a new preface by Robert Elms.

SINCE the war ended a lot of people have been trying to revive the habits they most enjoyed before 1939, and one of the most widespread of these habits is visiting the local. The pleasure that this habit affords is not perhaps lofty but it is very profound, and as dearly prized by Londoners who have a pub in every street as by country-dwellers who may have only one within miles. During the war, certainly, it was one of the habits they missed most. Whether they were parching in the desert, evacuated with their jobs to unfamiliar seaside towns or country villages or inland spas, or merely working night shift, many of them were thinking and talking mainly about the time when they would again be able to drop into the old friendly local and have a pint or two among their friends.

Some of them came back to find their local gone, but they were the unlucky ones; like most things, the pubs survived the war better than seemed likely at one time. All of them found changes. The local might not open at all on Sunday, or it might close early on Saturday night. The fatal words ‘Finished serving’ rang even more bleakly on the ear than the old familiar cry of ‘Time’.

But London still has most of its 4,000 pubs, and they still number amongst them pubs of every kind. Old, sham-old, and comparatively new; prosperous and neglected, smart and shabby; pubs standing forlornly in the midst of bomb-damage, with their top storey missing and one bar gone, and pubs lurking safely under the great piles of modern office blocks. There are pubs that were the pride of the rebuilders in 1939, and pubs that were scheduled for demolition and have been saved by the war; pubs that have taken their place among the sights of London and pubs that are unknown two streets away.

Nobody can profess to know all the pubs of London, and Ardizzone and I certainly make no such claim. We cannot even feel confident that we know enough about pubs to be able to generalise; among the few thousand that we have not come across, there may be enough exceptions to change all the rules.

But all the pubs I have ever used have one thing in common. Each one is somebody’s local. Each one has its regular customers who use it, for some reason, in preference to other pubs. It may be the nearest to where they live or work, but it may not. One of the saddest things about the beer shortage has been its unsettling effect on the regulars who, after walking past the Pineapple on their way to the Phoenix, find the Phoenix closed and have to walk back to the Pineapple again. But they still make the hopeful journey, and even if you have never spoken to them or they to you, you look at each other sympathetically when you finally stand side by side in the alien bar.

They all have their regulars. Even the sightseers’ pubs; there is no greater show-place in London than the Cheshire Cheese off Fleet Street, but its bar is used regularly by journalists, advertising men, photographers—all sorts of local workers who would never think of ordering the famous pudding, nor derive any satisfaction from sitting in Doctor’s Johnson’s seat. There are pubs that have a lower proportion of regulars than the average, but even the biggest pubs on circuses— the sort that bus-stops are named after—and the busiest station bars seem to have customers who ask for ‘the usual’ and call the barmaids by their first names.

Of course, there is no reason why one person should not have more than one local. In the more favoured parts of London you may have two or three near your home and another two or three near the place where you work, apart from any that happen to be conveniently situated, for instance at bus-stops and stations, between the two. How many pubs you use regularly depends upon your own taste and fancy and the extent to which you expect different things from pubs at different times. If you want to become an intimate of the house it is of course best to use as few houses as possible so as to use those few more, but if your ambition is merely to be nodded to when you come in, and sometimes to be served before you give an order, that degree of familiarity can be attained in a score of houses without any danger of drinking yourself to death. Even in these days, when barmaids and managers seem to be always on the move, the people who work in pubs are fairly observant and know their customers better than you would think. You find the proof of this when they move. A landlord who has never shown any sign of recognition in his old house will no sooner see you enter his new house than he hails you as an old friend, and it can be quite embarrassing to go into an unfamiliar pub and be greeted by a half-remembered barmaid with ‘Well, fancy that now. Who told you I’d come here?’

Other People’s Locals

This possible plurality of locals is the only excuse for this book. Anybody who really likes pubs can have quite a lot of locals of his own; he will enjoy visiting his friends in their locals; and he will find that to sample other people’s locals is one way of learning how the other half lives.

Your own local can be a club, a refuge, a home from home. But an enquiring spirit will feel sooner or later the stirrings of desire for discovery. Other pubs tempt you; you go home a different way, or get off the bus at a different place, to try the pub that you have always noticed and never visited; you let your walks lead you to pubs that you have passed when you were in a hurry or when they were closed; you begin to be curious about the pubs of the East End or the West End, as the case may be; you wonder whether the pubs of Chelsea or Chiswick, Hampstead or Highgate, are all that they are cracked up to be; you hear that a rare brew is on sale at some out-of-the-way London pub and you decide to go and find it. You make many discoveries and you draw many blanks. If the proportion of discoveries is high enough you reach the condition when you collect pubs hopefully, as a gourmet collects restaurants, and a pub you have not sampled becomes a challenge to go in.

This, of course, is a long job, if you are not to neglect your own locals whilst you explore. And it is an endless job. As you add to your list of pubs visited, you leave behind you an ever-increasing list of pubs to be visited again. There are those you found good enough to visit for pleasure, and those you found bad enough to make you wonder whether you were wrong the first time.

And any pub may have changed since you were there last. The changes are not so drastic now as they were before the war, when the brewers were busy pulling down houses in all directions under the twin slogans of Rebuilding and Redundancy; nor as they were during the bombing, when one had to have second and third strings for appointments made a day ahead (‘I’ll meet you at Ward’s Irish House in Piccadilly Circus; or if that’s gone, at the Standard across the way; and failing that, at the Punch House behind the Haymarket’); nor even as they were towards the end of the war, when bombed houses that one had written off would suddenly reopen and bring a new interest to life. But pubs still sometimes change brewers, let alone staff. You may be passing a pub that you have not been to for some months and think ‘I wonder if they’ve still got that nice barmaid’, or ‘that friendly landlord’, or even ‘that hideous old harridan who was so rude when I asked for a box of matches’, and in you go again.

The rewards of exploration are high. Pubs vary so prodigiously and so unexpectedly. You find them in all sorts of places, and you find all sorts of people in them. Neither neighbourhood nor exterior is any guide to what is within. A house with a long imposing facade may turn out to be only a few feet deep; a house with a modest entrance and a narrow frontage may stretch back to the next street, as do some of the pubs in Fleet Street and the Strand. Only the other day I was taken to a little country-like pub with an entrance up some steps in a mews, and the friend whose local it was laughed cruelly at my disillusionment when he led me through to the Saloon and we found ourselves among the white-collared habitués of the Harrington Hotel in Gloucester Road.

You can still find plebeian houses in expensive neighbourhoods, though you will find fewer and fewer of them, for the brewers have discovered them too and are doing all they can to make their revenues more consistent with their ground rents; and you can find the neatest and snuggest of houses in the dingiest streets (who, for instance, could wish for a trimmer place to lunch than the Saloon Bar of the White Horse in Poplar High Street, just before it runs into Pennyfields; and where could you find a brighter bar than at the Steam Packet amongst the coal-tips and the bomb damage in Nine Elms Lane?). Even the modernisation may be only skin-deep; it is true that sometimes an ancient exterior conceals a bar all light oak and linoleum, but many a glazed-tile front leads into an unimpaired Victorian bar.

As for the people, in London pubs you see Londoners, and as Dr. Johnson might have put it, the man who is tired of Londoners is tired of mankind. But if you want specialisation you can always find the specialised pubs. Sometimes they can be deduced from their surroundings but more often not. You would expect, for instance, to find a Continental atmosphere in the Swiss Hotel in Old Compton Street, but why should the Helvetia further up the road be quite normally English, whilst the York Minster in Dean Street confronts you with a wall-full of photographs of French boxers and cyclists, and French spoken freely on both sides of the bar? (The...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 6.10.2011 |

|---|---|

| Illustrationen | Edward Ardizzone |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Literatur |

| Reisen ► Hotel- / Restaurantführer | |

| Geschichte ► Teilgebiete der Geschichte ► Kulturgeschichte | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Pädagogik | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| Wirtschaft | |

| Schlagworte | Class • Faber Finds • lifestyle • Nostalgia • Pubs • Society |

| ISBN-10 | 0-571-28096-X / 057128096X |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-571-28096-4 / 9780571280964 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 4,9 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich