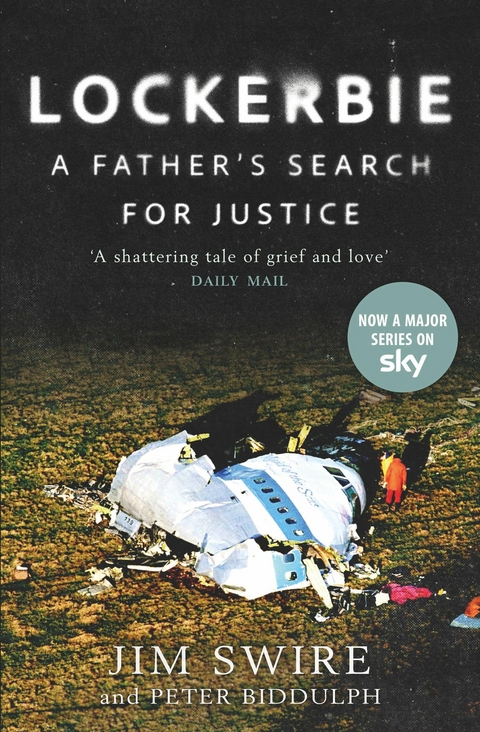

Lockerbie: A Father's Search for Justice (eBook)

272 Seiten

Birlinn (Verlag)

978-1-78885-305-7 (ISBN)

Jim Swire was a GP when his daughter was killed in the Lockerbie bombing. He became a spokesman for UK Families Flight 103 and has worked tirelessly for the truth to be told about the bombing.

Jim Swire was a GP when his daughter was killed in the Lockerbie bombing. He became a spokesman for UK Families Flight 103 and has worked tirelessly for the truth to be told about the bombing. Peter Biddulph began working with Jim to tell his story in 1999. Within ten days someone had accessed his computer and copied all notes and files, including the manuscript. Jim Swire's intention to write a book had made him a campaigner for the truth and also a 'person of interest'.

Preface

THIS BOOK IS partly the story of over thirty years of my life. Although of course it centres on the aftermath of the Lockerbie disaster, I believe it also has to be set in some autobiographical context. How could initial faith in the establishment take thirty years to convert into distrust towards all those touched by that addictive drug we call power?

One of my most vivid memories of early life comes from 1940 when I was five, crossing the Atlantic in a convoy, my father having been recalled to Britain after running the British garrison in Bermuda on the outbreak of war. He was an officer in the Royal Engineers and a man of principle of whom I was already deeply in awe. He and my mother Otta (née Tarn), and my elder sister Flora, were listening to words of defiance from Winston Churchill, speaking over the ship’s Tannoy: England would never surrender. What made it so memorable was that they were totally absorbed by that defiant and powerful rhetoric; it cut them off from the reality around them. I think that if a torpedo had chosen that moment to strike, they would have stayed exactly where they were to the end.

My parents had married late in their thirties and were steeped in the mores of the late Victorian era. In our households there were two communities, upstairs and down. Parents inhabited the ‘drawing room’, and we children were sent to fraternise with them with brushed hair and on best behaviour for an hour in the evening.

Once we were back in the UK, my father, Colonel Roger Swire, was away most of the time fighting WWII. I believe his psyche had been forever altered by his experience of the ‘Great’ War – as a young Royal Engineer subaltern aged seventeen he was sent on a horse and with a sabre to the trenches, winning a MC and Bar, but witnessing the mayhem of machine-gun bullets churning the mud of the parapets and sometimes the flesh of his men. One of the worst experiences seems to have been when playing tennis behind the lines with his best friend, the friend was shot dead on court by a sniper. None of these things would he ever mention himself. Meanwhile, Otta had to run the family on her own and apply the discipline that the Colonel would have required.

Looking back later, I wonder what it cost him to teach me to use a gun in Skye, or what memories were evoked for him when he and I used to go out onto the moors there in winter with lengths of wire to repair the phone lines blown off their poles by storms.

When the family settled into Orbost House in Skye in 1947, one of my regular tasks was to trim the wicks and clean the chimneys of the ordinary paraffin lamps, and to fill and pump up the tanks of the Tilley pressure-driven lamps which alone were powerful enough to light an entire space the size of the drawing room. The hiss of a Tilley and the smell of methylated spirit with which they had to be pre-warmed remain with me still.

It was necessary to ensure that any smell of spilled paraffin was scrubbed off me, and this was always achieved by our nanny, Louisa Macdonald, a Skye lady. She loved my elder sister Flora and myself like a mother and had been with the family from my sister’s birth. Both my grandmothers had come from Skye, and it was because of our family’s long association with the island that she was recruited from there. She had started with us when our family was billeted at number twenty-four the Cloisters in Windsor Castle, where my sister and I were born. ‘Louie’ had been with us in Bermuda, braved the Atlantic with us, and had lived to see and love our own children too. Like me, she was hugely in awe of the Colonel.

Sent down to England from the age of seven to stay in the best boarding schools, I think I was being prepared to take on the mantra of a leader. But the role did not fit; I felt I had neither the self-confidence nor the ambition.

School holidays were spent roaming the hills of Skye, bringing home meat and fish for the table. During term time Nanny, who had bought herself a shotgun, made up for shortages in my absence. No doubt my long-isolated hunting treks over the Skye moors, and fishing trips in my homemade single-seat canoe, reinforced my shyness.

National Service as a second-lieutenant in the Royal Engineers in Archbishop Makarios’s terrorist infested but beautiful island of Cyprus and in Port Said in the Suez crisis taught me about esprit de corps, plastic explosives, the workings of bombs, the sadness, madness and loss of war, and also about the shapes of organised religion and the power of the financial might of America.

After that came three lovely years reading geology in Cambridge where, on 21 June 1960, I met a delightful young trainee teacher, Jane, and on 16 December 1961 we married: a ceremony which forever transformed my life for the better. Jane is brave, tough and loving. Somehow she knew, twenty-seven years later, after Flora’s murder, that my campaign was at least in part my way of coping with the loss.

From 1960 I enjoyed my job as a TV technician in the BBC; electronics had been a major hobby, and ‘Auntie’ reinforced that with a professional training course. But when I finally did decide to read medicine, which meant initial years of penury, Jane backed my decision.

The arrival of our first child, Flora, changed the world for us. Flora was everything a first-born could possibly be. Even on the breast as a baby her eyes were looking around, weighing up her people and her world, full of fun and curiosity, bursting with energy. Soon she had a sister, Cathy, and then a brother, William, and we were a fortunate and happy family. Flora’s clever hands gave her skills in many hobbies including dressmaking.

Flora had a lovely voice and became an accomplished pianist and skilled guitar player, winning diplomas at music festivals. I vividly remember her singing to her own guitar when she was about ten in a croft house in Skye, with the croft’s budgerigars twittering in time to her beat, all of us crammed in around the peat fire. Having worked at the BBC I was into recording, but I still can barely listen now to that cosy evening ceilidh with young Flora singing ‘I dreamed the world had all agreed to put an end to war . . .’, and the words of love and appreciation that her fresh skills had evoked.

Later, Flora decided to study medicine, and I have fond memories of discussions between us about diseases old and new. Like most medical students she went through phases of believing that she had one of the diseases being studied. Once she became worried about a deeply coloured spot on one of her toes: was it a malignant melanoma? After close examination and a few giggles it was clearly not, but she being Flora I had to explain why I was sure that it was not.

There is no bond stronger than that between a mother and her child, and it shines through what Jane has written about those happy years before Flora’s murder. Jane’s words evoke the spirit of Flora as no others can; to read them blurs my eyes with tears.

Breaking the embargo against families being allowed to see the victims’ bodies, I arranged to visit the Lockerbie ice rink after the disaster, where our lovely Flora’s body had been thoughtfully arranged for me. She had received fatal injuries when the bomb exploded almost under her feet and the fuselage ripped apart at 31,000 feet, throwing her body into the screaming, freezing dark. She had landed on a green Scottish hillside, but her face had been so distorted by impact that I had to make sure it was indeed her body. The pathologist moved the sheet from over her feet, and there on her toe was the same dark mark which she and I had examined years before.

Mrs Thatcher attended the memorial service in Lockerbie. To us was read the story of the restoring to life of Lazarus. I suppose the vast majority of us there were agnostics, unable honestly to decide what, if anything, follows this life. For me it was a wildly inappropriate choice of reading, for the one thing we could not be granted was the return of our lost loved ones to be with their families again.

Within a month of the disaster I obtained a detailed warning from West Germany, received by the UK Government in October 1988, several weeks before the Lockerbie attack. It described the design and function of a series of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) built into domestic tape recorders and the like. It explained how they would always give a plane around thirty-five minutes of flight time before exploding, being fully automated.

I was also able to access a ‘warning about this warning’ sent on to Heathrow security by the UK Department of Transport just before the night of the Lockerbie attack. In it the Heathrow people were told: ‘Any item about which a searcher is unable to satisfy himself/ herself must, if it is to be carried in the aircraft, be consigned to the aircraft hold.’ The crass stupidity of this advice took my breath away, demolishing my faith in those who had been charged with the protection of our families. An early target for me became the improvement of aviation security, but the system proved arrogantly resistant to criticism, aided by Margaret Thatcher’s refusal to allow an enquiry.

On 21 December 1988 just such a bomb was duly loaded into the hold of our Flora’s aircraft at Heathrow. It exploded after thirty-eight minutes of flight at 31,000 feet over Lockerbie, just as the German police warning had predicted.

Was the failure of Margaret Thatcher’s government to act on that precise warning from Germany part of the reason why they denied us any inquiry? We do not of course know, for...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 6.5.2021 |

|---|---|

| Zusatzinfo | 4pp b/w plates |

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Recht / Steuern ► EU / Internationales Recht |

| Recht / Steuern ► Strafrecht ► Besonderes Strafrecht | |

| Recht / Steuern ► Strafrecht ► Kriminologie | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung | |

| Schlagworte | 1988 • Abdelbaset al-Megrahi • Attack • Catherine McCormack • CIA • Colin Firth • criminal • david harrower • december • Dr Jim Swire • family justice • FBI • Flora Swire • grief and loss • International Law • In the Name of the Father • intimidation • Jane Swire • Jim Sheridan • Justice • Law • Libya • Lockerbie • lockerbie bombing • Lockerbie Trial • Megrahi • My Left Foot • Netflix • Otto Bathurst • Pan Am • pan am flight 103 • Peaky Blinders • personal tragedy • Plane • plane crash • Scotland • Search for Justice • shocking stories • Sky BBC mini series • SKY TV • Starring Colin Firth • Terror • terrorism • terrorist attacks • the lockerbie bombing • True stories • UK Terrorism • victims of terrorism |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78885-305-9 / 1788853059 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78885-305-7 / 9781788853057 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 3,9 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich