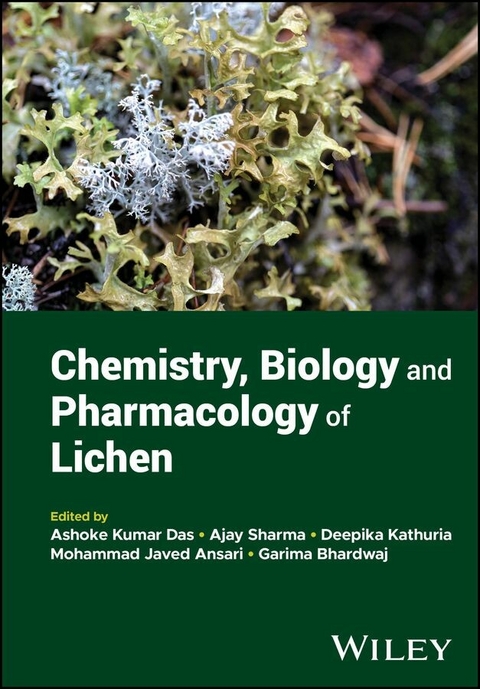

Chemistry, Biology and Pharmacology of Lichen (eBook)

352 Seiten

John Wiley & Sons (Verlag)

978-1-394-19069-0 (ISBN)

Lichen is a single entity comprising two or more organisms--most typically algae and fungus--in a symbiotic relationship. It is one of the planet's most abundant categories of flora, with over 25,000 known species across all regions of the globe. Lichens' status as a rich source of bioactive metabolites and phytochemicals, as well as their potential as bio-indicators, has given them an increasingly prominent role in modern research into medicine, cosmetics, food, and more.

Chemistry, Biology and Pharmacology of Lichen provides a comprehensive overview of these bountiful flora and their properties. It provides not only in-depth analysis of lichen physiology and ecology, but also a thorough survey of their modern and growing applications. It provides all the tools readers need to domesticate lichen and bring their properties to bear on some of humanity's most intractable scientific problems.

Chemistry, Biology and Pharmacology of Lichen readers will also find:

* Applications of lichen in fields ranging from food to cosmetics to nanoscience and beyond

* Detailed discussion of topics including lichen as habitats for other organisms, lichens as anticancer drugs, antimicrobial properties of lichen, and many more

* Detailed discussion on key bioactive compounds from lichens

Chemistry, Biology and Pharmacology of Lichen is ideal for scientists and researchers in ethnobotany, pharmacology, chemistry, and biology, as well as teachers and students with an interest in biologically important lichens.

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 4.6.2024 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie ► Botanik |

| Schlagworte | Biowissenschaften • Botanik • Chemie • Chemistry • Ecology & Organismal Biology • Flechten (Botan.) • Life Sciences • Molecular Pharmacology • Molekulare Pharmakologie • Ökologie • Ökologie u. Biologie der Organismen • plant science |

| ISBN-10 | 1-394-19069-7 / 1394190697 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-394-19069-0 / 9781394190690 |

| Informationen gemäß Produktsicherheitsverordnung (GPSR) | |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 5,2 MB

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich