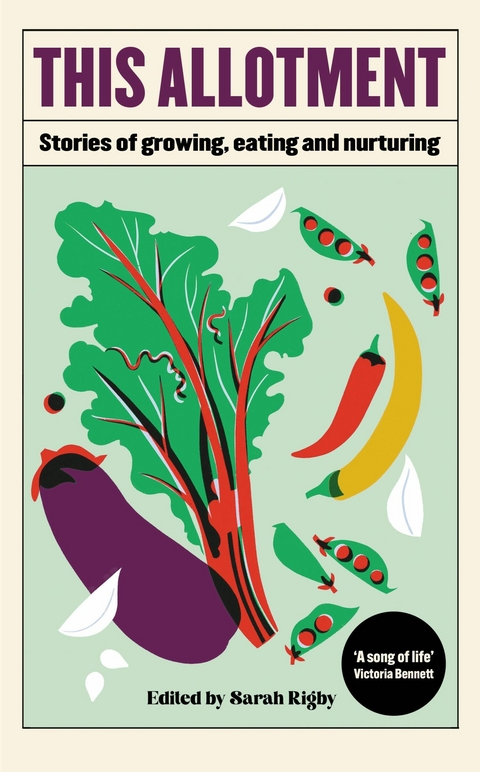

This Allotment (eBook)

224 Seiten

Elliott & Thompson (Verlag)

978-1-78396-789-6 (ISBN)

'Dip into these pages as an allotment sceptic and you may well find your mind is changed. If you have a plot, you'll be reminded of why all the hard work is worthwhile.' The Garden

This Allotment brings together thirteen brilliant contemporary writers in a glorious celebration of these entirely unique spaces: plots that mean so much more than the soil upon which they sit.

An allotment. A health-giving, heart-filling miniature kingdom of carrots, courgettes and callaloo. A microcosm for our societies at large as people claim their 'patch' and guard it protectively, but also of welcoming arms, gifted gluts and new recipes from overseas.

They are places of blowsy dahlias, cricket on the radio and cups of tea in tumbledown sheds; they are buzzing bees and the wisdom of weeds and seeds; they are resilience, resistance and freedom with a radical history and future. All life is here is this collection of vibrant original pieces on growing, eating and nurturing.

CONTRIBUTORS: Jenny Chamarette * Rob Cowen * Marchelle Farrell * Olia Hercules * David Keenan & Heather Leigh * Kirsteen McNish * JC Niala * Graeme Rigby * Rebecca Schiller * Sui Searle * Sara Venn * Alice Vincent

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 6.6.2024 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Natur / Technik ► Garten |

| Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Natur / Technik ► Natur / Ökologie | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie ► Ökologie / Naturschutz | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Geowissenschaften | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Physik / Astronomie | |

| Schlagworte | Alan Buckingham • alice vincent • Allotment • Allotment Month by Month • Charlotte Mendelson • Common Ground • Complete Gardener • entangled life • Essays • food writing • Forager’s Calendar • Gardener’s Almanac • Gardening • gardens of the National Trust • Gift • green spaces • growing • Health • Hedgerow Apothecary Forager’s Handbook • horticulturalist • how to read a tree • Huw Richards • Ian Spence • in the garden • Iverson • JC Niala • John Wright • Lia Leendertz • Marchelle Farrell • Merlin Sheldrake • monty don • National Trust • Nature • Nature Almanacs • Nature writing • Olia Hercules • Recipe • Rhapsody in Green • rhs • RHS Gardening of the Year • Rob Cowen • Tristan Gooley • uprooting • Urban • vegetables • Veg in one bed • Wellbeing • why women grow |

| ISBN-10 | 1-78396-789-7 / 1783967897 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-78396-789-6 / 9781783967896 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 6,5 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich