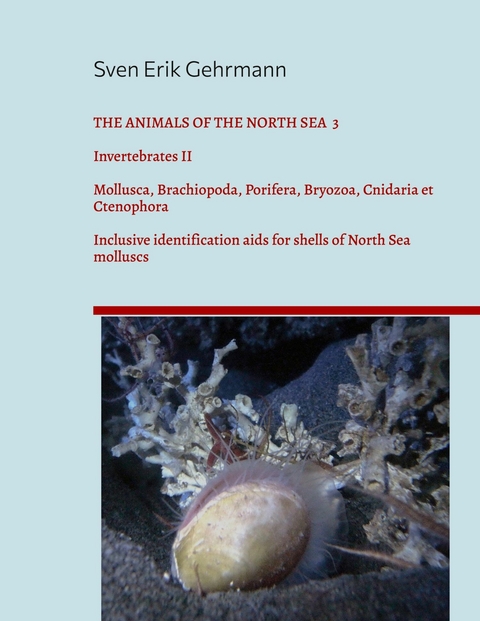

The Animals Of The North Sea 3 (eBook)

232 Seiten

Books on Demand (Verlag)

978-3-7578-3793-8 (ISBN)

Sven Erik Gehrmann, born in 1969 in Berlin and currently living in Norden near Norddeich on the coast of Lower Saxony, has been interested in everything that lives under water since he was a child. He has always been particularly interested in and fascinated by crustaceans and fish. Since 1983, he has been an enthusiastic hobby aquarist and nature fan of our native aquatic animals, especially North Sea animals. In his cellar he keeps a collection of various preserved species, so that whenever he gives a tour of the cellar, he is wont to say: "So, others have a carcass in the cellar? I have a few more..." (Estimated 500 preserved species. Or are there in-between 600?). So far, he has published various articles in aquaristics journals, ranging from North Sea animals to articles on anemone fish and various crustaceans. You can find him on the internet at: www.nordseefauna.org. In his publications, he never minces his words and calls a spade a spade, since obviously no one else does. In doing so, he has no regard for the false kind of "political correctness" that has been successfully installed everywhere here in order to preserve the appearance of decency. Nor does he profess to belong to any political party or direction, but only feels committed to the cause of the North Sea animals. Due to the dramatic climate changes in the North Sea within the last decade, he now sees himself as an independent nature activist, nature cryptographer and climate protector.

Class Gastropoda - Snails

The class of gastropods includes many species worldwide, but most of them live in the tropical seas, where they have reached their greatest diversity and colourfulness. In the northern seas there are relatively few species, which unfortunately rarely show bright colours. But there are some pretty exceptions here, too, as there are also colourful varieties of some species. For example, there are also red and yellow periwinkles, and the shells of some top shells are generally somewhat more colourful than those of other northern species. If you literally translate the word Gastropoda from the Greek, it actually means "stomach-footer". This suggests that snails are structured so, that their delicate innards lie directly over their soft foot tissue, on which they crawl. This soft "foot" can adapt very precisely to the ground, so that a snail can find a foothold on soft ground as well as on hard or highly structured ground. At the same time, some snails can develop very strong adhesive forces that make it almost impossible to detach them from the substrate without damage. Among the strongest snails in this fraction are certainly the families of limpets, which are detached from rocks by delicacy collectors with strong knives or crowbars. Many snails are pure vegetarians, grazing exclusively on the thin films of algae from the rocks, but there are also some predators, scavengers and even filter feeders among the snails, the latter being very difficult to keep alive in the aquarium. Almost all marine snails reproduce by releasing eggs and sperm into the seawater, from which the young snails develop through several larval stages which initially float in the plankton. But there are also some species that lay large clumps of eggs on the seabed, from which a few young develop. In the case of the predatory common whelk Buccinum undatum, the first hatchlings eat their unhatched siblings, so that a clump with perhaps two hundred eggs develops into only about a dozen young snails. This reproduction strategy may be sufficient for a predatory snail under natural conditions for the preservation of the species, but the populations of the common whelk in particular are already in such sharp decline in some parts of the North Sea due to human intervention of the chemical kind, that the animals are now also being doomed by their own reproduction strategy. Positive reports from research vessels claiming to still be able to demonstrate a high biological diversity in the North Sea should always be viewed with some scepticism. Because they often conceal the introduction of new animal species from other parts of the world, which endanger our endemic species. In very rare cases, marine snails also reproduce by the strategy of live-bearing, as is classically known to biologists from the river snail Viviparus viviparus. However, this snail is not a purely freshwater inhabitant, as it also enters brackish water and can tolerate low salinity levels. Therefore, it can also be found in coastal sloughs, ditches and in the Baltic Sea. Live-bearing species usually produce relatively few young, but they are born as fully developed miniature versions of their parents and can immediately live independently. Of course, this live birth cannot be compared to that of mammals, as the young snails mature in eggs in the body of the female. Before they are born, they hatch from the eggs as finished young in the mother's womb and are then "born" by the mother. Unfortunately, snail shells of species that prefer greater depths, can rarely be found on the beach after storm surges, but such shells are sometimes caught by shrimp-trawlers when fishing in water depths of more than 5 metres. The shells of some deeper-living species can also be found in shallow water in summer during low tide, if they have been dragged there by juvenile hermit crabs. These snails include species such as the common turritella Turritellinella tricarinata, the European necklace moon snail Euspira catena, the wentletrap Epitonium clathrus or the netted dog whelk Tritia reticulata. When collecting such shells, one should therefore make sure that they no longer contain hermit crabs, otherwise unpleasant-smelling surprises may occur. Among the snail species of the North Sea are also some record holders in the animal kingdom, whose records, however, have remained largely unknown until now. For example, the common mudflat snail Peringia ulvae, which is only a few millimetres in size, is one of the fastest snail species in the world, because it can move with the tidal current at a speed of up to 7 kilometres per hour. At the same time, this snail has probably also booked the record as the most common snail on the tidal flats, as up to one million specimens can be found on one square metre of tidal flats. The snail species found in the North Sea make up for their lack of colourfulness with their diversity and fascinating way of life, which varies greatly from species to species. It is a great pleasure not only to collect their shells, but also to observe living animals. The ecological relationships between snails and other marine organisms are also a broad and often unexplored field of activity for the biologist or amateur researcher. This is, because many connections and interrelationships are neither known nor have been sufficiently researched so far. It is very worrying, when species, which are actually known as common species, such as i.e. the common whelk, are on the retreat, leaving a gap that one cannot yet imagine who will fill in the future. The loss of one link in the food chain can have fatal consequences for the entire ecosystem of the North Sea, with other links also disappearing or migrating. Unfortunately, people usually only notice these connections when it is too late, and entire fishing sectors begin to collapse seemingly out of the blue. Therefore, it is unfortunately not at all unimportant whether species disappear or become rare. Therefore an appropriate monitoring should be set up for this on the part of the responsible agencies in order to be able to act before it is too late....

The river snail Viviparus viviparus.

Right:

The common whelk Buccinum undatum was temporarily considered extinct in parts of the German Bight. Although a ban on tributyltin as an antifouling agent brought about a certain recovery of the populations, the advancing climate change in the North Sea could still be the undoing of this cold-water species.

Sea Hare, Aplysia punctata (Cuvier, 1803)

The sea hare is not a true nudibranch, as it still has the remains of a tiny shell, which is well hidden between its body tissue. This snail is a true cosmopolitan, found in virtually all temperate and tropical oceans. Sea hares can reach more than 10 centimetres in body length, but they are still not easy prey for predatory animals. They defend themselves by secreting foul-tasting inky secretions when attacked. This is why they can be kept in an aquarium together with diverse fishes and crustaceans without any problems. As algae eaters, they are popular animals for marine aquaria and can live for several years in algae-rich sea-tanks. Unfortunately, if they do not find enough algae, they wither away quite quickly. Therefore, they are not suitable for tropical reef aquaria, which are usually low in algae, and can be kept here only temporarily to eradicate a temporary algae plague. The two specimens pictured here were collected on Gran Canaria and thus come from the northern Atlantic. But they are also found in the English Channel and in the southern North Sea, and it is to be expected, that they will move further and further north in the future due to the rising water temperatures in the North Sea. For the sea hare it is better not to touch it with bare hands, lest you provoke the animal to emit its defensive secretions. It is best to let the sea hare crawl into a small plastic container and then move it. If you catch sea hares yourself somewhere and want to bring them home alive, you should transport the sea hares individually. And, if possible, in small plastic containers, into which you put small pieces of activated charcoal to prevent the animal from poisoning itself during transport. Animals that have been collected in cold water should also be very slowly and gently acclimatised to warm water, otherwise you risk the immediate death of the animals. This is because the animals' metabolic processes run much slower in cold water than in a tropical environment, so that keeping animals in tropical conditions can also shorten their natural lifespan quite considerably. Therefore, responsible aquarium enthusiasts should think twice before collecting and importing animals as stock for their mostly tropical aquaria.

Green Velvet Snail or Green Elysia, Elysia viridis (Montagu, 1804)

The green velvet snail reaches a length of about 45 millimetres. It is very widespread, being found in the South Atlantic waters of South Africa as well as in the Mediterranean, the North Atlantic and the North Sea. With its mantle lobes, it imitates aquatic plants. With a bit of luck, it can therefore be found among stands of algae in sheltered places such as small harbours. However, their colouration varies between reddish and greenish shades depending on the food available. This results from the fact, that it forms an endosymbiosis with the chloroplasts of the algae it eats. Characteristic of the species are its reddish, greenish, and bluish spots on its entire body. It also has larger white or black spots on its antennae and head. The green...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 24.5.2023 |

|---|---|

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie |

| ISBN-10 | 3-7578-3793-2 / 3757837932 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-3-7578-3793-8 / 9783757837938 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 42,4 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich