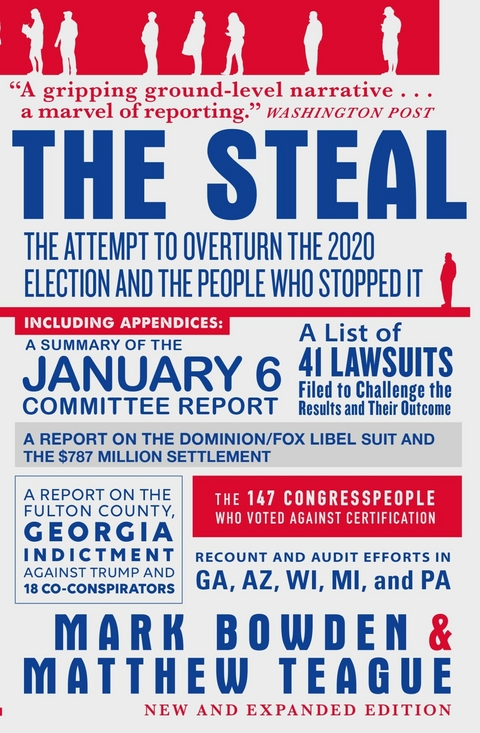

Steal (eBook)

320 Seiten

Atlantic Books (Verlag)

978-1-61185-875-4 (ISBN)

Mark Bowden is the bestselling author of Killing Pablo (Atlantic 2002), Finders Keepers (Atlantic 2003), Guests of the Ayatollah (Atlantic 2006) and Black Hawk Down, which was made into a successful film by Ridley Scott. Guests of the Ayatollah is his latest book. He is a national correspondent for the Atlantic Monthly.

In the sixty-four days between November 3 and January 6, President Donald Trump and his allies fought to reverse the outcome of the vote. Focusing on six states - Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin - Trump's supporters claimed widespread voter fraud. Caught up in this effort were scores of activists, lawyers, judges and state and local officials, among them Rohn Bishop, enthusiastic chairman of the Fond Du Lac, Wisconsin, Republican Party, who would be branded a traitor for refusing to say his state's election was tainted, and Ruby Freeman, a part-time ballot counter in Atlanta who found herself accused of being a 'professional vote scammer' by the President. Working with a team of researchers and reporters, Mark Bowden and Matthew Teague uncover never-before-told accounts from the election officials fighting to do their jobs amid outlandish claims and threats to themselves, their colleagues and their families. The Steal is an engaging, in-depth report on what happened during those crucial nine weeks and a portrait of the heroic individuals who did their duty and stood firm against the unprecedented, sustained attack on the US election system and ensured that every legal vote was counted and the will of the people prevailed.

Mark Bowden is the author of fifteen books, including Killing Pablo and Black Hawk Down. He reported at the Philadelphia Inquirer for twenty years and now writes for The Atlantic and other magazines. Matthew Teague is a contributor to National Geographic, The Atlantic, Esquire and other magazines, and executive producer of Our Friend, a feature film that premiered in 2021.

1

Election Day

TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 3, 2020

Donald Trump refused to believe he might lose. While some of his aides would tell him only what he wanted to hear, in the days before the election his own polling data said he would. Trump said no. He could feel it in his bones.

But . . . what if he lost? A man who grounds his very identity on winning has strategies for handling loss. For years, Trump had been laying out his. If the votes did not add up to victory, there was a reason. An obvious one. Everybody could see it. He had spelled it out again and again, warning even before his shocking victory in 2016 that the system was “totally rigged.”

Rigged by whom? Trump’s promise to “Drain the Swamp” was a sure applause line at his rallies. The expression long predated him, of course, referring to the nefarious ties between lawmakers and lobbyists, but Trump’s usage implied something more and kept enlarging. In time it became simply “The Swamp,” a thing he never clearly defined but that eventually seemed to encompass every entrenched institution in America. There was the “Deep State,” the career employees who made up the enduring machinery of government; the Democrat Party, stem and branch; unprincipled “career” politicians; the “lying” mainstream press; the technocrats who created and controlled the very internet platforms he and his supporters used; the Republicans who dared to criticize him; liberal academia . . . on and on the meaning expanded. Left-leaning and corrupt, The Swamp was an unyielding suck on Trump’s native genius, determined to drag him down, and with him the American dream.

Campaigning against Hillary Clinton, he had predicted “large-scale voter fraud” and had decried the American electoral process as fundamentally unfair. He forecast a sweeping crime capable of changing the nation’s course but was always vague about how it would actually work. Indeed, despite his claim that everybody knew it, there was no evidence of it in modern times. The Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank that tabulated voting fraud cases nationwide going back more than thirty years, listed only widely scattered instances committed by members of both political parties, capable of influencing—and even then only in rare instances—local election results. But the charge resonated with those who feared big government, the growing number and power of minorities, the whole modern drift of American society. Drawing on antiquated stereotypes from the era of Tammany Hall, Trump especially stressed corruption in big cities, where Democrats ruled and the population was heavy with African Americans.

“They even want to try and rig the election at the polling booths, where so many cities are corrupt. And you see that,” he said, campaigning in Colorado in 2016. “And voter fraud is all too common. And then they criticize us for saying that. . . . Take a look at Philadelphia . . . take a look at Chicago, take a look at Saint Louis. Take a look at some of these cities where you see things happening that are horrendous.” In his final debate with Clinton, he had refused to say whether, in the event he lost, he would even acknowledge the results. In that event, the numbers would be crooked.

Even victory did not allay this gripe. He continued to throw shade on the contest, questioning the validity of Clinton’s winning margin in the popular vote, eventually setting up a commission to investigate voter fraud. Asked whether Clinton’s certified numbers were accurate, the commission chief, Kris Kobach, said, “We may never know the answer to that.” Even after the probe found nothing and disbanded, Trump continued grooming his supporters to expect fraud.

Throughout his White House tenure, he used his elevated platform to spread this message. In November 2018, prior to midterms, Trump and his attorney general, Jeff Sessions, warned of wide-scale voter fraud. They offered no evidence. Trump said, “Just take a look. All you have to do is go around, take a look at what’s happened over the years, and you’ll see. There are a lot of people—a lot of people—my opinion and based on proof—that try and get in illegally and actually vote illegally. So we just want to let them know that there will be prosecutions at the highest level.” As ballots were still being counted in Florida’s races for governor and US Senate, Trump claimed on Twitter, “Many ballots are missing or forged, ballots massively infected.” No evidence of this surfaced, no one was prosecuted, and both Republican candidates ultimately won.

Still he continued impugning the voting process. The move to allow more mail voting during the pandemic gave him a new target. “Mail ballots are a very dangerous thing for this country, because they’re [Democrats] cheaters,” he said at a coronavirus press briefing on April 7, 2020. “They go and collect them. They’re fraudulent in many cases. . . . You get thousands and thousands of people sitting in somebody’s living room, signing ballots all over the place.” Pressed the next day about the “thousands and thousands” claim, Trump promised to provide evidence, and did not. There wasn’t any. He wasn’t making a case; he was sowing suspicion.

So Trump did have a strategy in case of defeat. He used fear of fraud to raise millions of dollars for his 2020 campaign, soliciting contributions on his campaign website with the words “FRAUD like you’ve never seen,” asking for donations “to ensure we have the resources to protect the results and keep fighting even after Election Day.”

On October 26, one week before votes would be cast, campaigning in Allentown, Pennsylvania, he said, “The only way we can lose, in my opinion, is massive fraud.”

GEORGIA

In the darkness of election morning, the first drop of water fell from the lip of a urinal in an Atlanta bathroom, splashing onto a black concrete floor. Every flood arrives with a first drop.

For months, within the walls of the State Farm Arena, water had risen in a pipe that led to the bathroom in the Chick-fil-A Fan Zone on the upper level. The arena’s maintenance staff had shut off the water on that level during the coronavirus pandemic, since crowds couldn’t come watch the ice skating shows or listen to Harry Styles sing. But thanks to a valve not quite shut or an O-ring worn by time, water in the pipe inched upward. Sometime in early November, it topped a curved trap and began filling the basin of the urinal, a Toto Commercial model in Cotton porcelain.

Now it spilled into the world, pouring onto the floor, seeking the lowest point in concrete worn smooth by ten thousand pairs of sneakers. It seeped into crevices, into the arena’s structure and interstitial spaces, down through the wires and ductwork, and finally collected and poured through the ceiling of the room below.

About five thirty in the morning, a few blocks away at the county’s election headquarters, Rick Barron’s phone rang and chirped with the bad news. He was director of Fulton County’s elections, and stood surrounded by banks of phones and televisions. Workers back at the arena should have started sorting early ballots, but now calls and text messages said they hadn’t. When the first workers arrived, in the dark and quiet, they’d heard the impossible sound of what seemed like indoor rain. Someone flipped on the lights and the workers found themselves standing on the edge of a storm.

Now Barron watched a video of the indoor flood. The image showed a vast room, with an array of ballot-processing machinery, tables where the workers normally sat, and big plastic bins full of ballots. Two of the workers always made an impression, even in grainy arena security footage. Ruby Freeman stood out with an Afro that matched her big personality. In normal times she ran a kiosk at the mall selling handbags, socks, and other ladies’ accessories, which she called Lady Ruby’s Unique Treasures. But during election season she helped out with temporary work. Her daughter, thirty-six-year-old Shaye Moss, wore her hair in recognizable long blond braids, and had worked for years for the Fulton County elections office. Doing election work meant early mornings and long hours but it gave the mother and daughter a close-up view of democracy in action, right in the room where ballots were gathered, sorted, and counted. But now this—water pouring from above—had brought the machinery of freedom to a stop.

Behind his pandemic mask, Barron sighed. He would hear about this from higher-ups at the state level, which was the last thing he needed. He already didn’t fit in here; he was the only white member of his election staff, to start. And the Atlanta political class found him odd. He was from Oregon, for one thing. At that moment, he wore a lanyard emblazoned with the logo for the Portland soccer team, of all things. He might as well drink Pepsi.

Now a rain cloud had burst, somehow, in his counting room.

Bonkers, he thought. He showed the video to Johnny Kauffman, an Atlanta radio reporter who had covered local elections for years and had embedded with the Fulton County staff. It seemed funny, in a bleak way. “Oh my God,” Kauffman told him. “It looks like it’s raining from the ceiling.”

“It could only...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 6.1.2022 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Naturwissenschaften ► Physik / Astronomie ► Angewandte Physik |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung ► Politische Systeme | |

| Sozialwissenschaften ► Politik / Verwaltung ► Staat / Verwaltung | |

| Schlagworte | 2020 election • Arizona • Bob Woodward • Brad Raffensperger • capitol insurrection • Democracy • democratic • Donald Trump • Georgia • Joe Biden • Michael Wolff • Michigan • Nevada • Pennsylvania • vote • Voting • Wisconsin |

| ISBN-10 | 1-61185-875-5 / 1611858755 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-61185-875-4 / 9781611858754 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 3,9 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich