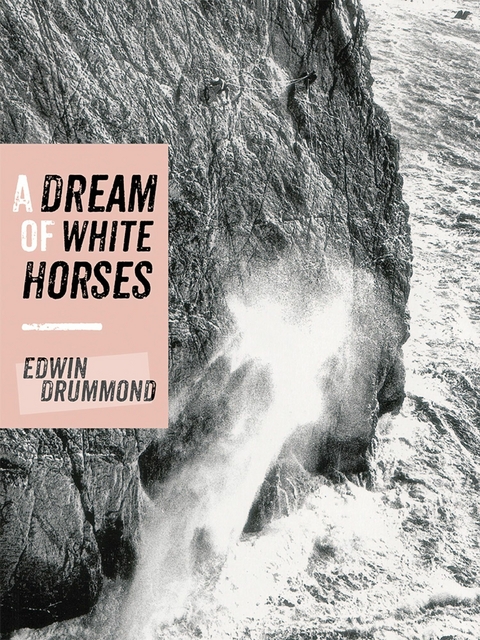

A Dream of White Horses (eBook)

300 Seiten

Vertebrate Digital (Verlag)

978-1-910240-22-9 (ISBN)

– BETWEEN THE LINES –

Under Stanage, a Sunday in late September, 1985. The air is kaleidoscopic with flies, sifted from the long, rain-bent grass, by sudden sunlight and a combing wind. Through the car window the ash trees are flocks of hummingbird-green leaves; leaving. A white butterfly totters past, Icarus for a day.

I’m sitting in the back of the VW camper with my shirt off; the Californian tan gone, a paleface again. For more than a year – after being pulled off the North America Wall – across the States, through Europe – Italy, Yugoslavia, France, I’ve been driving, looking for you all whom I left ten years ago.

Parked here for seven days and nights now. On a quick trip to Manchester and Accrington, in a chance conversation I heard about the extermination of the trout from the rivers by acid rain: ‘Though no one says anything,’ he said, ‘we just fish from big holes in the ground they keep stocked up.’ And, sitting here. I’ve seen you through the windscreen in canary-yellow and goldfish-orange anoraks and cagoules – and so many more of you! – drifting across the edge in all weathers; schools of climbers and hikers and flocks of hang-gliders drawn to the long purple trench, a breakwater against the swollen Pennines. Though you didn’t know I was here, watching and writing.

Last Tuesday I wandered up, with my boots dangling from one hand and an empty chalk bag from the other, to that wing of grit I clung to, uplifted, twelve years ago. Some of you were there. A little embarrassed to ask, nevertheless, you gave me a handful. I floated up, fingers white-feathering the edge of the arête, to all appearances unruffled.

‘How long have you been back?’ one of you asked, which made me feel less stiff. Though later, when I was working on that boulder problem I hadn’t done in over a decade, I wished you’d have waved, or called that you were leaving. For I’d noticed one of you come around the corner to see what I was up to. I watched you too for a while as you walked away down the track. You didn’t look back; you were looking where you were going.

Like the two quartz pebbles, not so much as blinking when I scratched my way up the face without them. And it was then, as I strolled back past, that I looked up. And realised: Well. Maybe. I went up a ways, a bit of caterpillary nonchalance – but the thoughts started pecking so I crept back to the van.

Perhaps if you’d have been there watching I would have done it. You could have given me a spot. I wouldn’t have had to ask even, I mean you’d have just understood that, well, I needed … Wouldn’t you?

I couldn’t have said that ten years ago. I felt it every time though that I leafed through climbing magazines in the States, always hoping to find that you’d not forgotten. I hadn’t ever been able to bring myself to tell you how much you’ve always meant. I just hoped or something that you’d see that I couldn’t simply go on climbing and say nothing.

I’m not complaining. The strange thing is that whenever we’ve met, you’ve always been really nice; polite. Of course I did notice the funny looks you’d give each other while I expounded, especially if I had my beret on, the one with the butterfly that looks as if it’s just come out of my ear. And you haven’t forgotten a thing! Only the other day Caroline asked me if I still ate dates. Which made me remember that perhaps my fingers were a bit stickier after I’d munched that block I hauled up in my socks in 1967 – for the only chalk we had back then was treacly experience – and maybe that was why I chattered that the ragged crack would go free. We talked on for a while, about the children and running marathons – we both wept at the end of our one and only – and soon, both relaxed. I had a second cup of coffee and looked around. There were several photos of Nick up in the house. One, of him looking out from his belay seat beneath the roof on the Salathé, had the hint of a smile, gently nervous, encouraging and warning at the same time; which was how I remembered him looking on me as I struggled to free the last move of the great wall section of the Rimmon route in 1970. I miss him. Drowned in an avalanche in the Himalayas, his two sons see his face every day at the head of the stairs as they rush off to school. Like the sky today semaphoring sun and shadow at the same time, confusing the insects, brushing the dust from the ledges and uncurling the fingers of ferns and climbers from their respective pockets, his look made you get up. And I sensed he was closer to trusting me than you. Or …

Monday at Phil’s: I put down the phone. I felt like I’d been beaten up. I didn’t care to ask Phil if he felt I was lacking in in … He knows me better than that. Don’t you Phil? The telephone call had been like that recurrent dream I used to have, in which I’m trying to hide in the cloakrooms at my junior school. I have no clothes on. I can feel the damp, black macintoshes. It is like being naked among a clutch of constables who haven’t noticed me yet. It’s not the first time that he’s put me to the wall.

But I feel almost grateful to him. As if I needed to be arrested.

‘That must have hurt,’ he added.

I mumbled ‘Yes, yes,’ reassuring him I was still on the line, as if he was a beginner dentist who needed to know I had nerves – and not a judge who’d once put me away. How was he to know I had escaped?

But how much of my willingness to take it from him is due to my getting softer, especially since the baby died and the realisation was born that at times I’d driven a bulldozer over people who looked up to me, putting my foot down, revving the hyperlogical arguments that got me through a degree in philosophy and two marriages unscathed (like bolting up a slab) and how much to the truth of what he said, and the speed at which those low blows cut through my unconditioned nether regions! – I have no way of telling.

I looked up at the mirror as if checking my x-ray. I was scarlet. When he said, ‘However, I have to admit that the climbing world is a hell of a lot more colourful because of your presence,’ I had to smile.

Before calling him up I’d had the idea of saying – which I dropped as soon as I heard his Harley Street-dark voice, ‘May I borrow your etriers?’ However, to tell him directly what I had only hinted at in my recent letter, in which, in passing, I renamed a famous national monument, would have made him feel I was even more fickle than he suspected.

‘You flit across the climbing scene every few years. Are you just the court jester? A lot of climbers think you’re a real publicity seeker. Any book you write must address the central question: What are you?’

‘“A literary thug” David said,’ said Terry, when I told him the next day, as if we three were wise mice to his big cat, and not literary men who needed to put their words where their mouths are. It was starting to come back: Sitting in Mac’s car in 1967 in the back next to him. Pete was in the front, Mac at the controls of his big, breasty Volvo, and we speedboated the bumpy road after Deiniolen, going downhill fast to Anglesey. I’d neither seen nor heard of him before. He was so frontal, demanding to know what my grading system meant, that I went limp beneath the heaviest armour-plated reply I could find to prevent him pricking my bubble. My system was, as I see it now, an attempt to mathematicise our rock dance. It was spawned by that promiscuous positivism in philosophy that set up traffic signals in the river of life we call speech, and which has constructed most climbing discourse nowadays to sound like a voice-printed bank statement, a telephone directory of names and grades and ratings.

I don’t recall what I said exactly in response to his grilling; no doubt it was as noetic as a geometrical point, having position but no magnitude, and probably made as much impression in the suddenly hushed car as a pin dropped in the Padarn on a Saturday night. Clad in my shorts and knee-length socks in the back, I felt as out of place among those iconoclasts as a racehorse being driven to the dogs. So it should have come as no surprise that when we reached the foot of Mammoth, he dropped his jeans and shat in the sea. ‘That offended you didn’t it,’ he jeered, Falstaffian, the brown clods switching back and forth while I looked – distinctly – off.

But I wonder too how many of us by now would have had our feet up by the fire, a pipe in our mouths, and Rebuffat’s latest book in our hands, after a stroll along our local outcrop on a Sunday afternoon, having pointed out some unconquerables we top-roped once, were it not for him: his rhythm and force, whitewater among the type setters: in a way his faithfulness. ‘Are you going to be one of these four year wonders?’ he said as Mac hit the gas over the Menai Straits. The godfather of climbing’s overworld, putting out contracts for Changabang, The Goblin’s Eyes, Cerro Torre, Everest the cruel way, whatever was new, whatever was never.

‘It may interest you to know,’ he told me over the phone, ‘you weren’t the first climber to make an anti-Apartheid protest. We did at Birmingham, just after Mandela was imprisoned.’ I’m still not sure whether to tell him or not.

But hadn’t he come all the way from Manchester to the crown court in London, where we were on trial after Nelson’s, to act as a character witness? With reservations: we’d been charged with having caused over five hundred pounds worth of damage to the lightning conductor – which I vehemently denied:

‘Come on you know me better than that!’

‘What about Linden?’ he shot back. So the Defence paid his train...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 12.12.2014 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | London |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Sachbuch/Ratgeber ► Sport |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Geowissenschaften ► Geografie / Kartografie | |

| ISBN-10 | 1-910240-22-2 / 1910240222 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-910240-22-9 / 9781910240229 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Größe: 1,9 MB

DRM: Digitales Wasserzeichen

Dieses eBook enthält ein digitales Wasserzeichen und ist damit für Sie personalisiert. Bei einer missbräuchlichen Weitergabe des eBooks an Dritte ist eine Rückverfolgung an die Quelle möglich.

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen dafür die kostenlose Software Adobe Digital Editions.

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen dafür eine kostenlose App.

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich