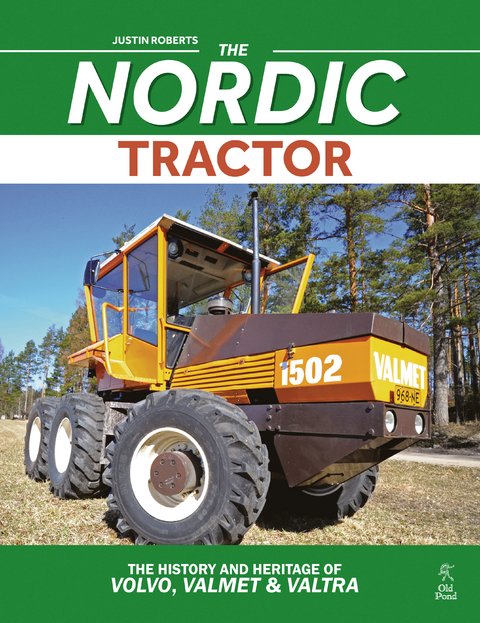

Nordic Tractor, The: The History and Heritage of Volvo, Valmet and Valtra (eBook)

200 Seiten

Old Pond Books (Verlag)

978-1-912158-13-3 (ISBN)

Justin Roberts is a freelance writer and photographer. He is a regular contributor to magazines covering both historic and contemporary agricultural machinery in Britain and Ireland. Although born in Britain, he has lived in Ireland since 2007 and is married with two daughters.

Justin Roberts is a freelance writer and photographer. He is a regular contributor to magazines covering both historic and contemporary agricultural machinery in Britain and Ireland. Although born in Britain, he has lived in Ireland since 2007 and is married with two daughters.

Finland is not a country that many of us are familiar with. We have all heard of it but should we be asked much beyond the name of its capital, or to point to roughly where it is on the map then many of us would probably struggle. The town of Suolahti would be more obscure still, yet it is in this central part of the country that there lies a factory which holds something of the very essence of Finland and the Nordic countries as a whole. The factory belongs to Valtra, which is now part of the global agricultural group AGCO. It’s therefore somewhat unsurprising to learn that it usually produces over 8,000 tractors a year. This in itself is not a particularly large number – the new Holland plant at Basildon produces three times that – but these tractors brought into the world amongst the forests and lakes have a legacy behind them that is somewhat different to those that we may be more familiar with here in western parts of Europe.

How far back this legacy actually stretches depends upon one’s inclination to seek out industry’s roots in the Nordic countries. The links that tie the modern Valtra tractor factory in Finland to the arrival of industry in Sweden are strong and undeniable; in fact, they may be traced deeper still and we can find them burrowing down to the very time and place of the birth of the Industrial Revolution itself, the British midlands of the eighteenth century. This might sound rather distant and obscure, but the story of Valtra can be followed way back across the North Sea to the small village of Norton in Hales, deep in the heart of rural Shropshire. The reason we might consider this happily innocent settlement as the starting point of our tale revolves around the year 1774 when Samuel Owen was born to his farming parents of that parish. In the great annals of history his name barely registers but he was destined to become one of those disciples of the great technological bubble that we now consider to be the start of the modern world and he was instrumental, as many other British engineers were, in taking the seeds of this expertise and knowledge and planting them firmly in European countries and beyond.

The reasons why Britain, and more specifically England, happened to become the cradle of industrialisation are beyond the scope of this book, yet the mills, factories, docks, canals and notorious slums are inescapably the work of home-grown entrepreneurs and engineers as they rapidly absorbed and deployed the new knowledge that a more disciplined scientific establishment was providing. These methods and techniques were also carried around the globe as the country exported its initial success to all the continents while deriving a great dividend from doing so. It is only natural that the profits generated were appreciated by the rapidly expanding merchant classes but somehow one feels that the landed gentry never really took to the idea of the bricks, smoke and waste despoiling what they considered the pastoral ideal, an ideal which they had owned and ruled and shaped as the whim took them, for centuries and was now threatened by elements outside their control. However, we cannot dwell too long on the likely origin of the grief and antagonism that has expressed itself in the division between workforce and owners over the intervening years, for Samuel Owen, our lowly born son of toil, has grown into a bright young man who is giving lessons in arithmetic and geometry to others, despite having barely attended school himself. After a number of small jobs, going into service at a nearby manor and then working on canal boats, he gained apprenticeship to a carpenter and helped eke out his means by teaching the subjects for which he had found a passion and talent. As may be imagined, this was never going to prove a suitable situation for such an intelligent and ambitious fellow, so having been captivated by the potential of steam power he made his way to the new factory established by the inventor of the much-improved steam engine, James Watt. This was around 1795, nearly 30 years after Watt had developed his idea of a separate condenser for the then grossly expensive to run Newcombe steam pumps. Watt had experienced some difficulty in getting his improvement onto the market and it wasn’t until he teamed up with Matthew Boulton in 1775 that the idea became a commercial reality, six years after he had patented it in 1769. The names Boulton and Watt became synonymous with early steam engines, although it must be borne in mind that they didn’t at first make them in a factory, but licensed the technology to others and despatched their own engineers, and often James Watt himself, to supervise the building of the engine components in diverse forges around the country for assembly on-site. It wasn’t until 1795 that the then wealthy James Watt built a new foundry at Soho for the exclusive manufacture of engines and it was about this time that Samuel Owen joined the new venture as a model maker.

The 1770s also saw another invention that, on the face of it, was hardly an earth-shattering development, but in fact it provided a tremendous impetus to the Industrial Revolution and Britain’s leading role within it. The device presented a major leap forward in cannon boring technique and was intended to create more perfectly round holes in cast iron gun barrels. The inventor was John Wilkinson, who hailed from Cumbria in the very north of England. He had expanded the family business by establishing various ironworks in North Wales and Shropshire and his patent for boring naval cannon was taken out in 1775. So successful and useful was it that the Navy took steps to overturn the patent four years later and so prevent Wilkinson enjoying a monopoly in gun supply. By the end of 1775 Wilkinson had refined the technique to support the cutting tool at either end while still turning the cylinder and the following year, the first Boulton and Watt steam engine with accurately-machined cylinders was installed at one of his furnaces to supply the air draught. These cannon and cylinder boring devices are regarded by many as the world’s first machine tools and are the forerunner of all the CNC tools and robots we see in factories today. It is also suggested that Henry Maudslay’s later improvements to the basic lathe are the germ of such tools, but these didn’t appear until around 1800.

As we shall see in due course, modifying a method designed to create weapons to one that produces more civilised products was a development to be echoed 170 years later in the Nordic countries, as facilities designed to conduct warfare more effectively were put to peaceful use. Over two centuries ago, it was James Watt who saw the cannon hole borer as the perfect tool for creating cylinders for his steam engines while, more recently, a particular armaments factory in Finland adapted its expertise in producing artillery to making tractors; but we are getting ahead of ourselves on that point. Meanwhile, back in the eighteenth century, the inventor of the boring device was another of those manufacturing geniuses upon whose efforts the Industrial Revolution was built. John Wilkinson became a friend and collaborator with Boulton and Watt but is less well known than either, despite being a major force behind the construction of the world’s first iron bridge, a structure that still stands at a place that is now a World Heritage Site and is known simply as Ironbridge.

By the late 1700s, James Watt was equipped with a rudimentary knowledge of thermodynamics (a branch of science that he had pioneered), a good practical experience of building and operating steam engines, the wealth of a man who has seen his inventiveness put to productive use and now the tools to continue improving the engines which were enjoying a greater popularity than ever. This increase in demand for steam power was a consequence of industry outgrowing the supply of natural power available to it. Water and windmills were highly dependent upon weather and terrain and so a reliable source of energy to turn the cogs and mills throughout Britain and beyond suddenly became hugely important to the economy. Samuel Owen, our newly married carpenter from Shropshire, found himself at 21 within the very heart of this great upheaval and his abilities were quickly recognised by Boulton and Watt who encouraged his further learning and studies throughout his time with them. However, famed and respected as they were for the production of steam engines, the company was not the only supplier in the field, for up in Yorkshire there was, in the city of Leeds, a firm by the name of Fenton, Murray and Wood who were bitter rivals to Boulton and Watt. In fact, so strong was the animosity between the two companies that the younger James Watt, son of the founder, later went so far as to purchase the land adjoining the upstart’s premises in a bid to stop them expanding, a plan that appeared not to have worked too well as the Yorkshire firm enjoyed a strong reputation for the quality of their engineering and it didn’t seem to have interfered with their business to any great extent. It is now a matter of speculation as to whether the poaching of staff, alongside various well-documented episodes of industrial espionage upon both sides, helped fuel this antagonism; we can’t even be sure that it happened at all, yet it would appear that sometime around 1800, Owen moved up to Leeds and had been working for Fenton, Murray and Wood for several years until, once again, fate knocked upon his door.

In 1804, he was preparing to move to America where his skills would doubtless have been in...

| Erscheint lt. Verlag | 7.11.2017 |

|---|---|

| Verlagsort | Mount Joy |

| Sprache | englisch |

| Themenwelt | Natur / Technik ► Fahrzeuge / Flugzeuge / Schiffe ► Allgemeines / Lexika |

| Natur / Technik ► Fahrzeuge / Flugzeuge / Schiffe ► Nutzfahrzeuge | |

| Naturwissenschaften ► Biologie | |

| Technik | |

| Weitere Fachgebiete ► Land- / Forstwirtschaft / Fischerei | |

| Schlagworte | classic tractors • farm tractors • tractor history • Transport • Valtra |

| ISBN-10 | 1-912158-13-2 / 1912158132 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-1-912158-13-3 / 9781912158133 |

| Haben Sie eine Frage zum Produkt? |

Kopierschutz: Adobe-DRM

Adobe-DRM ist ein Kopierschutz, der das eBook vor Mißbrauch schützen soll. Dabei wird das eBook bereits beim Download auf Ihre persönliche Adobe-ID autorisiert. Lesen können Sie das eBook dann nur auf den Geräten, welche ebenfalls auf Ihre Adobe-ID registriert sind.

Details zum Adobe-DRM

Dateiformat: EPUB (Electronic Publication)

EPUB ist ein offener Standard für eBooks und eignet sich besonders zur Darstellung von Belletristik und Sachbüchern. Der Fließtext wird dynamisch an die Display- und Schriftgröße angepasst. Auch für mobile Lesegeräte ist EPUB daher gut geeignet.

Systemvoraussetzungen:

PC/Mac: Mit einem PC oder Mac können Sie dieses eBook lesen. Sie benötigen eine

eReader: Dieses eBook kann mit (fast) allen eBook-Readern gelesen werden. Mit dem amazon-Kindle ist es aber nicht kompatibel.

Smartphone/Tablet: Egal ob Apple oder Android, dieses eBook können Sie lesen. Sie benötigen eine

Geräteliste und zusätzliche Hinweise

Buying eBooks from abroad

For tax law reasons we can sell eBooks just within Germany and Switzerland. Regrettably we cannot fulfill eBook-orders from other countries.

aus dem Bereich